Research Article - Journal of Mental Health and Aging (2022) Volume 6, Issue 1

Pathway linking emotional suppression to depression and anxiety in cancer patients under chemotherapy: The mediating role of ego-strength.

Rasoul Heshmati1*, Chris Lo2, Maryam Parnian Khooy3, Elaheh Naseri3

1Department of Psychology, Faculty of Education and Psychology, University of Tabriz, Tabriz, Iran

2Department of Psychiatry; and Behavioural Sciences and Health Research Division, Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto, Canada

3Department of Psychology, Faculty of Education and Psychology, University of Mohaghegh Ardabili, Ardabil, Iran

- *Corresponding Author:

- Rasoul Heshmati

Department of Psychology, Faculty of Education

and Psychology, University of Tabriz, Tabriz, Iran

E-mail: psy.heshmati@gmail.com

Received: 19-Nov-2021, Manuscript No. AAJMHA-21-47899; Editor assigned: 22-Nov-2021, PreQC No. AAJMHA-21-47899 (PQ); Reviewed: 06-Dec-2021, QC No. AAJMHA-21-47899; Revised: 20-Dec-2021, Manuscript No. AAJMHA-21-47899 (R); Published: 27-Dec-2021, DOI:10.35841/aajmha-6.1.105

Citation: Heshmati R, Lo C, Khooy MP, et al. Pathway linking emotional suppression to depression and anxiety in cancer patients under chemotherapy: The mediating role of ego-strength. J Ment Health Aging. 2022; 6(1):105

Abstract

Background: Ego-strength, the developmental qualities which begin to animate man pervasively during successive stages of life, has an important role in psychological adaptation to cancer, especially when considering the outcomes of emotional suppression in cancer patients. However, the modulating effects of ego-strength on emotional suppression and symptoms of depression and anxiety has not been studied among cancer patients in previous research. This study aimed to investigate whether ego-strength mediates the relationship between emotional suppression and symptoms of depression and anxiety in cancer patients. Methods: 120 cancer patients were recruited from a private hospital in Tabriz to complete baseline questionnaires. Depression, anxiety, ego-strength and emotional suppression were assessed by BDI-II, BAI, PIES and WAI respectively. Mediation models were tested using structural equation modeling, controlling for age and gender. Results: Emotional suppression was positively associated with depression and anxiety, and negatively associated with ego-strength. Ego-strength was negatively associated with depression and anxiety. Ego-strength partially mediated the relationship between emotional suppression and depression, and fully mediated the relationship between emotional suppression and anxiety. Conclusion: Ego-strength may help prevent the onset or unfavorable course of depression and anxiety in cancer patients.

Keywords

Cancer, Depression, Anxiety, Emotional suppression, Ego-strength.

Introduction

A diagnosis of cancer can be worrying and is frequently associated with anxiety and depression [1]. Boyes and et al. evaluated a heterogeneous sample of cancer patients and found that the point prevalence of anxiety was 22% and the point prevalence of depression was 13% at 6 months post – diagnosis [2]. Also, 9% of patients presented with comorbid anxiety and depression. Other studies have shown that patients with breast cancer usually present varying levels of depressive symptoms [3]. The symptoms of anxiety in cancer patients are similar to other people’s anxiety symptoms. In some patients, in addition to general symptoms of anxiety such as fear, anxiety, hand tremor, shortness of breath, feelings of stinging something in the throat and palpitations, there are other symptoms that exist in cancer patients including: catastrophic thinking to the disease and the feeling of cancer relapse. Also the symptoms of depression include losing energy and interest, feelings of guilt, having problems in concentrating, losing appetite, and thoughts of death or suicide. Other symptoms include the changes in activity level, cognitive abilities, speech and vital functions (such as sleep, sexual activity and other biological functions) [4]. In cancer patients, untreated anxiety can produce problems about control of symptoms, disturbance in decision making related to treatment, social interaction, quality of life and weak coherence [5], and depression can lead to dysfunction in interpersonal, social and occupational functions of the patients [6], metastasis, pain and a higher rate of cancer symptoms [7]. The ability to regulate emotions, including tendencies toward emotional suppression, can play an essential role in regulating and moderating the effects of psychological avoidance on depression and anxiety. Suppression of emotion can be defined as a person's effort to decrease emotional expression of a certain emotion and/or their effort to decrease or eliminate thoughts or outward expression of this said emotion [8]. For example, an individual who experiences sorrow in reaction to losing their job might suppress this sorrow by attempting to hide any discernible signs (i.e., facial expressions) of their sorrow to their family and friends, or by externally declareing an opposite emotional reaction (e.g., "putting on a smile") [9]. In Summary, emotional suppression can be defined as an internalization of emotions during emotional arousal [10]. People repeatedly and rapidly forget that emotional status has a direct and profound influence on physical and mental health [11]. Emotional suppression has been reported to be associated with medical illness including cancer [12]. Some researchers have argued that emotional suppression may be an important risk factor for cancer [3]. Empirical evidence has accumulated to support the relationship between emotional suppression and psychosocial maladjustment such as depressive symptoms in patients with breast cancer [13]. For example, Schlatter and Cameron showed that anger suppression was associated with higher level of depression in breast cancer patients during chemotherapy [14]. The results of another study showed that emotional suppression was associated with the level of depressive symptoms in women newly diagnosed with breast cancer and anger suppression might play a unique role in the depressive symptoms among women newly diagnosed with breast cancer. Emotional expression in a supportive group environment improved the management of disease-related emotion and reduced distress. Nakatani et al. found that cancer patients with emotional suppression showed higher level of psychological distress and reported more negative emotions than the patients with emotional expression after receiving their diagnosis. The results of the other study showed that suppression was associated with higher anxiety and depression [15]. Furthermore, emotional expression can predict fewer depressive symptoms [16].

The expression or suppression of emotions has been associated with ego-strength. One of the factors that enables one to maintain his or her emotional stability in the face of internal and external stressors is ego-strength [17]. Ego-strength has been defined as a measure of the effectiveness with which the ego is performing its task of adapting to the demands of reality [18]. In other words, it is the ego’s task to evaluate the requirements of reality and to see that the individual’s needs are met within that framework. Ego strength is a power used by a person to face life difficulties, from the light to heavy ones. If it is good, the person must be able to keep his/her psychological stability while facing with stress, which is caused by either internal or external issues [19]. Ego-strength can also be understood as a measure of the “internal psychological equipment or capacities that an individual brings to his or her interactions with others and with the social environment” [20]. Ego-strength encompasses the capability of an individual to showcase resilience, remain emotionally stable and deal effectively with stressful or frustrating situations, and is associated with healthy communication between self and others [21]. Research into ego-strength includes the study of ego defense mechanisms like suppression, rationalization, denial etc. that help us deal with the reality [21].

As a measurable construct, ego-strength is composed of specific psychosocial abilities associated with resolving the stages of development according to Erikson. The capacity for hope, will, purpose, competence, fidelity, love, care and wisdom are dependent on the achievement of developmental milestones stretching from infancy to later adulthood [18]. Researchers believe that ego-strength is an important factor that can predict psychological health and treatment compliance in people with chronic disease [22]. Jamil, Atef Vahid, Dehghani and Habibi in their research showed that ego-strength has positive and significant correlation with mental health [23]. Spielberger found that people with high ego-strength are less susceptible to anxiety [24]. The results of Chansiya and Jogsan’s research reveal 0.54 positive correlation between ego-strength and anxiety [18]. Sheppard et al. indicated that weakness of egostrength was associated with depressive symptoms, accounting for 32% of the variance [20].

Considering that anxiety and depression are important clinical outcomes affecting quality of life in cancer, investigating the factors affecting them can provide more effective psychological treatments for patients. Ego-strength is one of these variables that can play an important role in person’s mental health and may modulate the effects of emotional suppression in cancer patients. However, the mediator role of ego-strength between emotional suppression and symptoms of depression and anxiety has not been studied among cancer patients in previous research. We aimed to test whether ego-strength may mediate the relationship between emotional suppression and symptoms of depression and anxiety in cancer patients.

Methods

Participants and procedure

We recruited Iranian patients with cancer attending a private hospital in Tabriz from April through May 2019 to complete a cross-sectional questionnaire package. The eligibility criteria included being able to read and write, and being in chemotherapy. Exclusion criteria included a history of alcohol and drug abuse, having another chronic illness, or a history of psychiatric disorder. All participants provided informed consent. The objectives of the study were described to participants and they were assured that all questionnaires are anonymous, and participation is voluntary. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Tabriz.

Measures and instruments

Beck anxiety inventory (BAI): This measure of anxiety contains 21 items assessed on a 0 (no) to 3 (severe) scale [25]. Scores may range from 0 to 63 and are classified as follows: 0–7 minimal or no anxiety, 8–15 mild anxiety, 16–25 moderate anxiety and over 26 severe anxiety. The Persian (Farsi) version of BAI has been shown to have good reliability (r=0.83), validity (r=0.72), and internal consistency (alpha=0.92) [26].

Beck depression inventory-II (BDI-II): This measure of depression contains 21 items rated from 0 (none) to 3 (severe) [27]. Scores may range from 0 to 63. The classification of the total score is as follows: <10, none or minimal depression; 10– 18, mild to moderate symptoms of depression; 19–29, moderate to severe depression; and 30–63, severe depression. The Persian (Farsi) translation of this questionnaire has been validated and shown to have acceptable internal consistency (alpha=0.87) and test-retest reliability (r= 0.74) [28].

Weinberger adjustment inventory (WAI): The WAI (Weinberger, & Schwartz, 1990) assesses psychological adjustment including distress, self-restraint and defensiveness [29]. In the present study, we used the self-restraint and defensiveness subscales. The 30-item self-restraint subscale measures impulse control, suppression of aggression, sense of responsibility, and consideration of others (e.g., "Doing things to help other people is more important to me than almost anything else"). The 22-item defensiveness subscale assesses denial of distress and suppressive defensiveness or claims of absolute restraint (e.g., “I never act like I know more about something than I really do”). Participants rate each statement on a fivepoint scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). A total score that can range from 52 to 260 was generated to measure the tendency toward emotional suppression, with higher scores indicating more suppression. In our study, the WAI had adequate internal consistency (alpha=0.75).

Psychosocial inventory of ego-strength (PIES): The 64-item PIES assesses ego-strength, which refers to the accumulation of protective psychosocial characteristics over the life span [30]. This validated scale was devised to measure eight protective qualities that include the capacity for hope (e.g., “When I think about the future, I feel optimistic”), sense of purpose (e.g., “Fear keeps me from striving for many of my goals”), experience of competence (e.g., “I have strengths that enable me to be effective in certain situations”), and the ability to form loving relationships (e.g., “I don't think I have really loved anyone outside of my family”) [31]. Items are answered on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (does not describe me well) to 5 (describes me well). It generates a total score ranging from 64 to 320, with higher scores indicating greater ego-strength. In the present study, internal consistency was high (alpha=0.90).

Statistical analysis

The data was analyzed by using SPSS 22 and Amos 18 software. Overall, less than 1% of items were missing. A single imputation using the expectation maximization algorithm was used to replace these missing values.

Descriptive statistics were calculated and Pearson correlations assessed the relationships between ego-strength, emotional suppression, depression and anxiety. Structural equation models (SEM) were used to examine whether ego-strength mediated the relationship between emotional suppression and depression, and in a separate model, anxiety. In the hypothesized mediation models, emotional suppression was the independent variable (IV), ego-strength was the mediator variable (M), and depression and anxiety were respective dependent variables (DV). Age (as a continuous variable), gender (0 female, 1 male), and disease stage (0 early, 1 advanced) were included as possible covariates. To evaluate the goodness-of-fit of our models, we report on the χ2/df, the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), the Comparative Fit Index criterion (CFI) and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) [32]. A χ2/df value ≤ 3 is indicative of good model fit. For the TLI and CFI, values ≥ 0.90 were considered indicative of good fit. An RMSEA value ≤ 0.08 was considered adequate.

Results

See Table 1 for descriptive statistics on the sample. Mean age was 76.07 years although there was a wide range from 60 to 100 years, and the sample was fairly balanced in terms of gender. Most individuals were early stage, and breast and colon cancer were the most common sites of disease.

| Variable | Description | Min - Max | Cr. Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | 76.07 (9.39) | 19-83 | |

| Male | 45.80% | ||

| Female | 54.20% | ||

| Cancer Stage | |||

| Stage I | 50.80% | ||

| Stage II | 37.50% | ||

| Stage III | 6.70% | ||

| Stage IV | 5% | ||

| Type of cancer | |||

| Colon | 20% | ||

| Stomach/Esophagus | 17.50% | ||

| Lung | 5.80% | ||

| Prostate | 13.30% | ||

| Breast | 31.70% | ||

| Cervical | 2.50% | ||

| Lymphoma | 9.20% | ||

| Months living with cancer | 19.53 (21.23) | Jan-96 | |

| Emotional suppression | 262.92 (19.71) | 211-328 | 0.75 |

| Ego strength | 220.75 (32.80) | 114-289 | 0.9 |

| Anxiety | 15.68 (10.50) | Jan-56 | 0.89 |

| Non | 21.70% | 0-7 | |

| Mild | 37.50% | Aug-15 | |

| Moderate | 22.50% | 16-25 | |

| Severe | 18.30% | 26-56 | |

| Depression | 18.92 (10.80) | Feb-46 | 0.88 |

| Non | 21.70% | 0-9 | |

| Mild | 30.80% | Oct-18 | |

| Moderate | 29.20% | 19-29 | |

| Severe | 18.30% | 30-46 |

Table 1. Sample characteristics (N=120).

See Table 2 for the correlation matrix. Patients with higher levels of emotional suppression had lower levels of egostrength (r=−0.23, p<0.05). In addition, emotional suppression was positively correlated with depression (r=0.45, p<0.01) and anxiety (r=0.21, p<0.05). Ego-strength was negatively correlated with depression (r=−0.59, p<0.01) and anxiety (r=−0.41, p<0.01). Gender was also significantly correlated with emotional suppression (r=−0.19, p<0.05) and depression (r=−0.20, p<0.05), such that women were more emotionally suppressive compared to men (female M=2.66 SD=19.61 vs. male M=2.58, SD=19.19), and more depressed (female M=20.93 SD=12.02 vs. male M=16.58, SD=8.68). Age was positively associated with emotional suppression (r=0.23, p<0.05) and depression (r=0.27, p<0.01). Age and ego-strength were also negatively associated (r=−0.22, p<0.05).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Emotional suppression | - | |||||

| 2 Ego strength | -0.23* | - | ||||

| 3 Depression | 0.45** | -0.59** | - | |||

| 4 Anxiety | 0.21* | -0.41** | 0.59** | - | ||

| 5 Gender | -0.19* | -0.004 | -0.20* | -0.15 | - | |

| 6 Age | 0.23* | -0.22* | 0.27** | 0.07 | 0.33** | - |

Table 2. Pearson correlation matrix (N=120).

Models fit indices

Emotional suppression was specified as the independent variable and ego-strength, the mediator. Depression was the dependent variable in one model, and anxiety was the DV in a separate model. A direct effect of emotional suppression on the DV was also specified in each case. Age and gender were included as covariates. The depression model had sufficient goodness-offit: χ2=3.95, df=2, χ2/df=1.97, p=0.14; TLI=0.91; CFI=0.98; RMSEA=0.09. Also, the anxiety model fit the data very well: χ2=2.28, df=2, χ2/df=1.14, p=0.32; TLI=0.98; CFI=0.99; RMSEA=0.03 (see Table 3).

| χ2 | df | χ2/df | P | TLI | CFI | RMSEA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression model | 3.95 | 2 | 1.97 | 0.14 | 0.91 | 0.98 | 0.09 |

| Anxiety model | 2.28 | 2 | 1.14 | 0.32 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.03 |

Table 3. Fit indices of the models.

Path coefficients

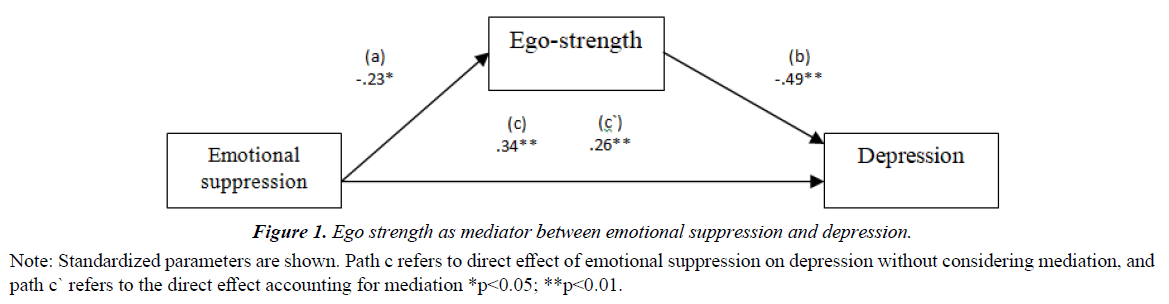

Figure 1 displays the depression model with mediation by ego-strength. Emotional suppression predicted ego-strength (b=−0.23, p<0.05; i.e., path a in Figure 1). Ego-strength predicted depression (b=−0.49, p<0.01; i.e., path b in Figure 1). Emotional suppression still significantly predicted depression even with ego-strength in the model (b=0.26, p<0.01; i.e., path c` in Figure 1). If ego-strength is excluded from the model, the direct effect of emotional suppression on depression is b=0.34, p<0.01 (i.e., path c in Figure 1).

Figure 1: Ego strength as mediator between emotional suppression and depression.

Note: Standardized parameters are shown. Path c refers to direct effect of emotional suppression on depression without considering mediation, and path c` refers to the direct effect accounting for mediation *p<0.05; **p<0.01.

The significance of the indirect effect of emotional suppression was tested using the Bootstrap estimation procedure. We generated 2000 bootstrapping samples from the original data set (N= 120). Table 4 displays the indirect effect and its associated 95% confidence intervals. Consistent with our hypothesis, emotional suppression had an indirect effect on depression via ego-strength and this effect remained significant after controlling for gender and age (b=0.13, p<0.05).

| Model pathways | β | Sig. | 95% Bias corrected CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upper bound-Lower bound | |||

| Depression model | |||

| Total effect | [0.19 to 0.47] | ||

| Emotional suppression →depression | 0.34 | 0.001 | |

| Indirect effect | [0.02 to 0.26] | ||

| Emotional suppression →depression | 0.13 | 0.015 | |

| Direct effect | [0.13 to 0.38] | ||

| Emotional suppression → depression | 0.26 | 0 | [-0.39 to -0.03] |

| Emotional suppression → ego-strength | -0.23 | 0.011 | [-0.62 to -0.36] |

| Ego-strength → depression | -0.49 | 0 | |

| Anxiety model | |||

| Total effect | |||

| Emotional suppression → anxiety | 0.19 | 0.012 | [0.04 to 0.32] |

| Indirect effect | |||

| Emotional suppression → anxiety | 0.08 | 0.04 | [0.04 to 0.16] |

| Direct effect | |||

| Emotional suppression → anxiety | 0.12 | 0.137 | [-0.03 to 0.27] |

| Emotional suppression → ego-strength | -0.19 | 0.048 | [-0.35 to -0.02] |

| Ego-strength → anxiety | -0.41 | 0.001 | [-0.50 to -0.24] |

Table 4. Results for the total, indirect, and direct effects of emotional suppression on depression and anxiety via ego-strength.

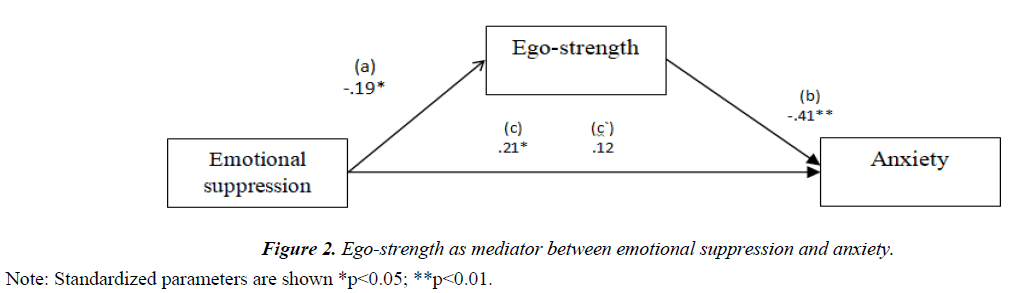

The anxiety model is shown in Figure 2. The pathway between emotional suppression and ego-strength was significant (b=−0.19, p<0.05; i.e., path a in Figure 2). The pathway between ego-strength and anxiety was also significant (b=−0.41, p<0.01; i.e., path b in Figure 2). There was no remaining direct effect of emotional suppression on anxiety with ego-strength in the model. If ego-strength is excluded from the model, the direct effect of emotional suppression on anxiety is b=0.21.

The bootstrapped 95% confidence interval (CI) confirmed that the indirect effect of ego-strength in the relationship between emotional suppression, and the anxiety was significant (b=0.08, p<0.05). As hypothesized, ego-strength was a full mediator, and this mediation remained significant after controlling for the only significant covariate, age.

Discussion

In this study, we found that emotional suppression had a direct effect on depression, consistent with contemporary evidence, for example Fila-Jankowska, & Szawinska [33]; Marroquin, Czamanski-Cohen, Weish, & Stanton [34]; Young, Sandman, Craske [35]. Emotional suppression acts as a defense mechanism and leads to avoiding and inhibiting threatening information and the lack of expression of unpleasant emotional experiences [29]. Cancer patients who do not express their emotions and suppress them are more susceptible to depression than those who express their emotions [36]. When negative emotions (such as anger, fear, hatred, etc.) have not been expressed, they may fester into a pervasive negative attitude toward the self, making the person further prone to depression. On the other hand, the results of Werner-Seidler, Banks, Dunn and Moulds’ study showed that reduced capacities to down regulate heightened negative affect are common to both anxiety and depression [37], whereas reduced ability to regulate positive affect may be more specific to depressive disorders [35]. Regarding this issue, it can be said that cancer patients who, in addition to suppressing their negative emotions, continuously suppress their positive emotions in an attempt to deaden all feeling, may also be prone to depression [38]. Properly expressing and managing positive emotions and sharing it with others can increase their effects in cancer patients.

We found that ego-strength had a mediating role between emotional suppression and symptoms of depression and anxiety, after controlling for age and/or gender. This is a novel finding that builds upon prior work which had shown that emotional suppression is associated with greater anxiety and depression in cancer patients [15]. The ability to express to regulate and express emotions was associated with resolving the conflicts of the eight Eriksonian stages that form a strong ego. When a person suppresses their emotions, they actually suppress a part of themselves, which weakens the hope, will, purpose, sense of competence, and other strengths that are related to ego. The existence of a strong ego can help psychological adaptation to life challenges like cancer and lessen the likelihood of depression and anxiety. This finding that ego-strength can predict depression is consistent with Sheppard et al. [20], and Hyphantis et al. [39] In the Freudian view, ego-strength referred to the ability to manage the demands and conflicts between Id, Superego and the requirements of the environment. From this perspective, ego-strength helps to maintain emotional stability in the context of stressful conditions in which one can easily feel helpless. Lack of ego-strength is one of the main indicators of psychological pathology in the psycho-dynamic approach [40]. Weakness of ego is associated with inefficient defense mechanisms, and lack of compromise and the capacity to deal with failure [41]. Ego-strength or maturity allows individuals to maintain emotional stability when coping with internal and external stressors.

Freud believed that the occurrence of mental disorders was the result of fixation in the early stages of growth. These fixations cause defects in the growth and functioning of the ego [42]. The inability to cultivate ego processes, such as judgment, moral reasoning, and reality testing can lead to mental harm. Hence, persons who have weak ego will lack readiness to adapt to reality consistent with observed correlations between low egostrength, anxiety, loss of control over consciousness thoughts and a lack of influence on the environment.

In cancer patients, there is the possibility that ego-strength itself may be weakened by illness and because of reliance on suppression as a coping mechanism, they are not able to control their negative emotions, or manage their daily stress and anxiety. This avoidant method of coping can increase emotional distress and implies less ability to accept the unpleasant realities of medical illness with consequent poor self-management and worsening of clinical outcomes.

Study limitations

Since the design is cross-sectional, the present research fail to infer that the change of the ego-strength could causally lead to the latter improvement of anxiety and depression in cancer patients under chemotherapy. Also, this study was only carried out on those doing chemotherapy, we should be cautious in generalizing the results to those who are not on chemotherapy stage. Furthermore, another limitation of the present study is the self-reporting of the questionnaires which can create biases in responses, the limitation of sampling from one hospital and one ethnicity during a limited time period. Considering these limitations, we recommend other researchers to conduct studies about patients in different treatment phases, other ethnicities and over more extended time periods. As well as, a better research design that allows causal influence should be taken into careful consideration in the following research.

Clinical implications

The study findings provided new evidence for the role of egostrength as a mediator between emotional suppression and anxiety/depression in patients with cancer. One of the clinical implications of this study is the need for health care providers to identify the psychological problems of cancer patients. Regular assessment of anxiety and depression can help health care providers recognize cancer patients with emotional problems and provide suitable psychological interventions. Given that emotional suppression affects the ego-strength and depression, educational programs for managing and expressing the positive and negative emotions in cancer patients with emotional suppression can help patients to manage the difficult conditions of the disease and improve their mood. Also, in patients with lower ego-strength, psychoanalytic treatments can focus on increasing patients’ ego-strength to overcome their psychoemotional distress.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we found that suppression of emotions can be a predictor of depression in patients with cancer and that egostrength was found to be an important mediator of relationship between emotional suppression and symptoms of depression and anxiety. Future work may seek to investigate how to promote ego-strength in the context of illnesses such as cancer and to reduce reliance on maladaptive coping mechanisms like suppression.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank the cancer patients who participated in this study.

References

- Mathews A, Ridgeway V, Warren R, et al. Predicting worry following a diagnosis of breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2002;11(5):415-18

- Boyes AW, Girgis A, D'Este CA, et al. Prevalence and predictors of the short-term trajectory of anxiety and depression in the first year after a cancer diagnosis: A population-based longitudinal study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(21):2724-9.

- Li L, Yang Y, He J, et al. Emotional suppression and depressive symptoms in women newly diagnosed with early breast cancer. BMC Womens Health. 2015;15(1):1-8.

- Tel H, Tel H, Do?an S. Fatigue, anxiety and depression in cancer patients. Neurol Psychiatry Brain Res. 2011;17(2):42-5.

- Weinberger MI, Bruce ML, Roth AJ, et al. Depression and barriers to mental health care in older cancer patients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26(1):21-26.

- Gross JJ. Antecedent – and response –focused emotion regulation: divergent consequences for experience, expression, and physiology. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;74(1):224-237.

- Chahar Mahali S, Beshai S, Feeney JR, et al. Associations of negative cognitions, emotional regulation, and depression symptoms across four continents: International support for the cognitive model of depression. BMC Psychiatr. 2020;20(1):1-2.

- Gross JJ, Levenson RW. Emotional suppression: Physiology, self-report and expressive behavior. J Pers Soc Psychol. 64(6) (1993) 970-986.

- J. Patel, P. Patel, Consequences of repression of emotion: Physical health, mental health and general well-being, J Psychother Pract Res. 1 (3) (2019) 1-16.

- Giese?Davis J, Spiegel D. Suppression, repressive?defensiveness, restraint, and distress in metastatic breast cancer: Separable or inseparable constructs? J Pers. 2001;69(3):417-49.

- Iwamitsu Y, Shimoda K, Abe H, et al. Anxiety, emotional suppression, and psychological distress before and after breast cancer diagnosis. Psychosomatics. 2005;46(1):19-24.

- Schlatter MC, Cameron LD. Emotional suppression tendencies as predictors of symptoms, mood, and coping appraisals during AC chemotherapy for breast cancer treatment. Ann Behav Med. 2010;40(1):15-29.

- Peh CX, Liu J, Bishop GD, et al. Emotion regulation and emotional distress: The mediating role of hope on reappraisal and anxiety/depression in newly diagnosed cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2017;26(8):1191-7.

- Martino ML, Gargiulo A, Lemmo D, et al. Longitudinal effect of emotional processing on psychological symptoms in women under 50 with breast cancer. Health Psychol Open. 2019;6(1):2055102919844501.

- Ziadni MS, Jasinski MJ, Labouvie-Vief G, Lumley MA. Alexithymia, defenses, and ego strength: Cross-sectional and longitudinal relationships with psychological well-being and depression. J Happiness Stud. 2017;18(6):1799-813.

- Chhansiya BM, Jogsan YA. Ego Strength and Anxiety among Working and Non-working women. Int J Indian Psychol. 2015;2(4):23.

- Petrovic ZK, Peraica T, Kozaric-Kovacic D. Comparison of ego strength between aggressive and non-aggressive alcoholics: a cross-sectional study. Croat Med J. 2018;59(4):156-65.

- Sheppard VB, Llanos AA, Hurtado-de-Mendoza A, et al. Correlates of depressive symptomatology in African-American breast cancer patients. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7(3):292-99.

- Singh N, Anand A. Ego-strength and self-concept among adolescents: A study on gender differences. Int J Indian Psychol. 2015;3:46-54.

- Settineri S, Mento C, Santoro D, et al. Ego strength and health: An empiric study in hemodialysis patients. Health. 2012;4(12):1328-1333.

- Jamil L, Atef Vahid M, Dehghani M, et al. The mental health through psychodynamic perspective: The relationship between the ego strength, the defense styles, and the object relations to mental health. Iran J Psychiatr Clin Psychol. 2015;21(2):144-54.

- Spielberger CD. Conceptual and methodological issues in anxiety research. Anxiety: Current trends in theory and research. 1966:481-93.

- Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, et al. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consulting Clin Psychol. 1988;56(6):893.

- Kaviani H, Mousavi AS. Psychometric properties of the Persian version of Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI). Tehran Univ Med J. 2008;66(2):136-140.

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, et al. An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of general psychiatry. 1961;4(6):561-71.

- H. Ghassemzadeh, R. Mojtabai, N. Karamghadiri, N. Ebrahimkhani, Psychometric properties of a Persian?language version of the Beck Depression Inventory?Second edition: BDI?II?PERSIAN, Depression and anxiety. 21(4) (2005) 185-92.

- Weinberger DA, Schwartz GE. Distress and restraint as superordinate dimensions of self?reported adjustment: A typological perspective. J Pers. 1990;58(2):381-417.

- Markstrom CA, Sabino VM, Turner BJ, et al. The psychosocial inventory of ego strengths: Development and validation of a new Eriksonian measure. J Youth Adolesc. 1997;26(6):705-32.

- Bentler PM. Fit indexes, Lagrange multipliers, constraint changes and incomplete data in structural models. Multivariate Behav Res. 1990;25(2):163-72.

- Fila-Jankowska A, Szawi?ska A. Suppression of negative affect in cancer patients. Trauma and defensiveness of self-esteem as predictors of depression and anxiety. Pol Psychol Bull. 2016;47(3):318-26.

- Marroquín B, Czamanski-Cohen J, Weihs KL, et al. Implicit loneliness, emotion regulation, and depressive symptoms in breast cancer survivors. J Behav Med. 2016;39(5):832-44.

- Young KS, Sandman CF, Craske MG. Positive and negative emotion regulation in adolescence: Links to anxiety and depression. Brain Sci. 2019; 9(4):1-20.

- Beutler LE, Daldrup R, Engle D, et al. Family dynamics and emotional expression among patients with chronic pain and depression. Pain. 1988;32(1):65-72.

- Werner-Seidler A, Banks R, Dunn BD, et al. An investigation of the relationship between positive affect regulation and depression. Behav Res Ther. 2013;51(1):46-56.

- Dryman MT, Heimberg RG. Emotion regulation in social anxiety and depression: A systematic review of expressive suppression and cognitive reappraisal. Clin Psychol Rev. 2018;65:17-42.

- Hyphantis TN, Christou K, Kontoudaki S, et al. Disability status, disease parameters, defense styles, and ego strength associated with psychiatric complications of multiple sclerosis. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2008;38(3):307-27.

- Weiner IB, Tennen HA, Suls JM. Handbook of psychology, personality and social psychology. John Wiley & Sons; 2012.

- Carvalho AF, Hyphantis TN, Taunay TC, et al. The relationship between affective temperaments, defensive styles and depressive symptoms in a large sample. J Affect Disord. 2013;146(1):58-65.

- Seaton CL, Beaumont SL. Pursuing the good life: A short-term follow-up study of the role of positive/negative emotions and ego-resilience in personal goal striving and eudaimonic well-being. Motiv Emot. 2015;39(5):813-26.

- Leube D, Whitney C, Kircher T. The neural correlates of ego-disturbances (passivity phenomena) and formal thought disorder in schizophrenia. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2008;258(5):22-7.

- Gold SN. Relations between level of ego development and adjustment pattern in adolescents. J Pers Assess 1980;44(6):630-38.

- Stanton AL, Danoff?burg S, Huggins ME. The first year after breast cancer diagnosis: hope and coping strategies as predictors of adjustment. Psychooncology. 2002;11(2):93-102.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref