Research Article - Journal of Clinical Dentistry and Oral Health (2022) Volume 6, Issue 5

Incidence of Class I vs. Class II dental caries in general population-A retrospective study

Tasleem Abitha S and Anjaneyulu K*

Department of Conservative and Endodontics, Saveetha Dental College and Hospitals, Saveetha Institute Of Medical and Technical Science (SIMATS), Saveetha University, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India

- Corresponding Author:

- Anjaneyulu K

Department of Conservative and Endodontics

Saveetha Dental College and Hospitals

Saveetha Institute Of Medical and Technical Science (SIMATS)

Saveetha University, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India

E-mail: kanjaneyulu.sdc@saveetha.com

Received: 08-August-2022, Manuscript No. AACDOH-22-70345; Editor assigned: 10-August-2022, PreQC No. AACDOH-22-70345(PQ); Reviewed: 24-August-2022, QC No.AACDOH-22-70345; Revised: 29-August-2022, Manuscript No. AACDOH-22-70345(R); Published: 05-Sep-2022, DOI:10.35841/aacdoh-6.5.121

Citation: Tasleem Abitha S, Anjaneyulu K. Incidence of Class I vs. Class II dental caries in general population-A retrospective study. J Clin Dent Oral Health. 2022;6(5):121

Abstract

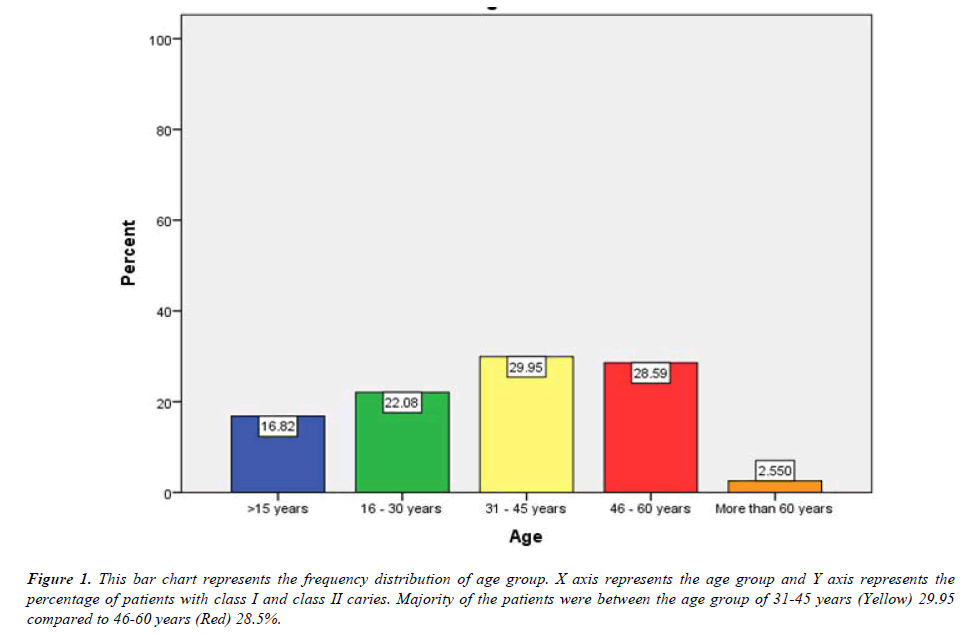

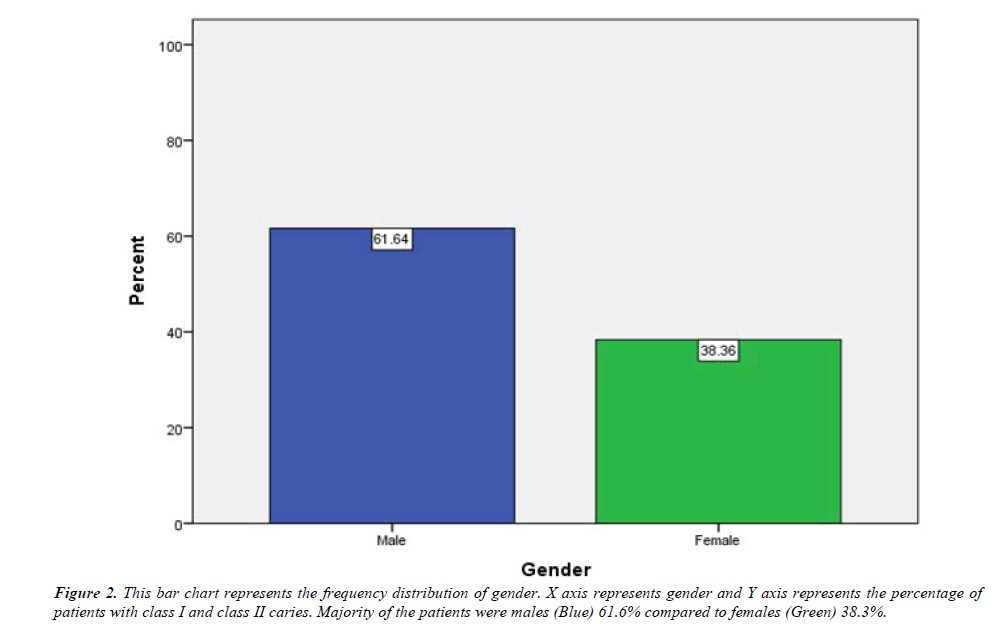

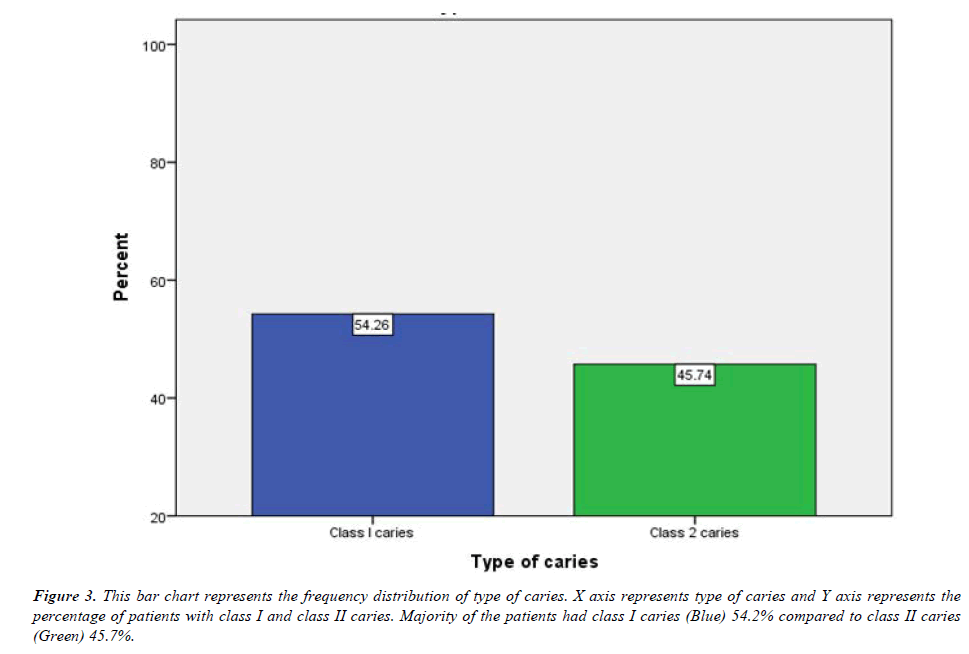

Introduction: The prevalence of dental caries due to the continuous improvement of living conditions, improved self-care practices, effective use of fluorides, adoption of healthy lifestyles and implementation of preventive oral care programs while in developing countries increasing the level of dental caries and treatment need has been observed. Materials and methods: This study is a retrospective cross sectional study conducted in a Private Dental Institution, in Chennai to determine the class I vs. class II dental caries with the approval from the Institutional Review Board. It included demographic data of the patients along with dental status of each individual. The data collection was done by reviewing the patient's record and analysed the data of 86000 patients between June 2019 and March 2021. Results: From our current study it is seen that, majority of the participants who had class I and Class II caries were between the age group of 31-45 years (29.9%) followed by 46-60 year (28.5%), 16-30 years (22%), >15 years (16.8%) and more than 60 years (2.5%). From our current study it is seen that, around 54.2% of the population had class I caries whereas 45.7% of the population had class II caries. Conclusion: Within the limits of the current study it has been proven that, Class I caries are more prone to affect the general population than Class II caries.

Keywords

Dental caries, Class I caries, Class II caries, Poor oral hygiene, Innovative technology.

Introduction

The prevalence of dental caries due to the continuous improvement of living conditions, improved self-care practices, effective use of fluorides, adoption of healthy lifestyles and implementation of preventive oral care programs while in developing countries increasing the level of dental caries and treatment need has been observed [1].

Dental caries is the most common chronic disease worldwide. Dental caries is a multifactorial disease; several factors play a role in the initiation and progression of the lesion including environmental factors, host, and behavioural factors [1,2]. The distribution of caries has changed in the last century and exclusively recent data indicate that about 90 percent of carious lesions occur in the pits and fissures of permanent posterior teeth and that molar tooth are most susceptible to caries [3].

Class I caries include occlusal surface, buccal and lingual pits of posterior teeth and lingual surface of anterior teeth whereas Class II are involving proximal surface of posterior teeth [4]. In the recent years the global distribution of dental caries presents a varied picture, most of the countries with low caries prevalence are experiencing an unprecedented increase in caries prevalence and severity of dental caries hence the present study was aimed at determining the prevalence of dental caries, effect of the gender and the positioning of the teeth and their surfaces in the oral cavity on the prevalence of dental caries [5].

When a cavity is prepared to remove a carious lesion it is typically slightly larger than the size of the lesion itself. On the tooth surface it has an outline form which refers to the perimeter of the cavity [6]. This is also usually a little larger than the perimeter of the carious lesion. The cavity must have subtle features incorporated in its form to ensure longevity of the restoration. These features are typically referred to as retention and resistance forms [7].

Retention forms represent features that enable a cavity to retain a restoration in place without movement. For example, if one was to think of a Class I cavity as resembling a box, when the base of the box (pupal floor) is slightly wider than its opening (occlusal) there is virtually no means for a restoration placed in such a cavity to get dislodged in one piece [6,8]. Resistance forms refer to the cavity design that prevents fracture of either the restoration or the tooth itself. For example, amalgam is a brittle material and if used in thicknesses less than 2 mm it may undergo fracture under loads of mastication [9,10]. Therefore, a cavity prepared for amalgam restoration must provide for adequate amalgam thickness on the occlusal of at least 2 mm [11]. Enamel is highly brittle, however, dentin which is softer acts as a cushion to support enamel and prevent its fracture. If an enamel margin was left unsupported during cavity preparation for amalgam, it may undergo fracture under forces of mastication [9]. Our team has extensive knowledge and research experience that has translate into high quality publications [12-32].

Hence, the aim of the study is to access the incidence of class I vs. Class II dental caries in general population.

Materials and Methods

This study is a retrospective cross sectional study conducted in a Private Dental Institution, in Chennai to determine the class I vs. class II dental caries with the approval from the Institutional Review Board.

Data collection

Data is extracted from Patient management software of Saveetha dental college from the time period February 2020 to February 2021 based on the following inclusion and exclusion criteria’s.

Inclusion criteria

Patients who had Class I and Class II caries

Exclusion criteria

• Patients below the age of 18 years.

• Retreatment cases.

• Teeth with pulpal involvement.

Data Analysis

The data collected were reviewed and cross verified. The collected data is entered in MS Excel sheet, and transferred to SPSS version 21 for analysis. Independent variables were PID, Name; Dependent variables were age, gender, tooth number, apical preparation size. Chi square test was used to analyse the association. P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Results were presented in the form of bar diagrams.

Results

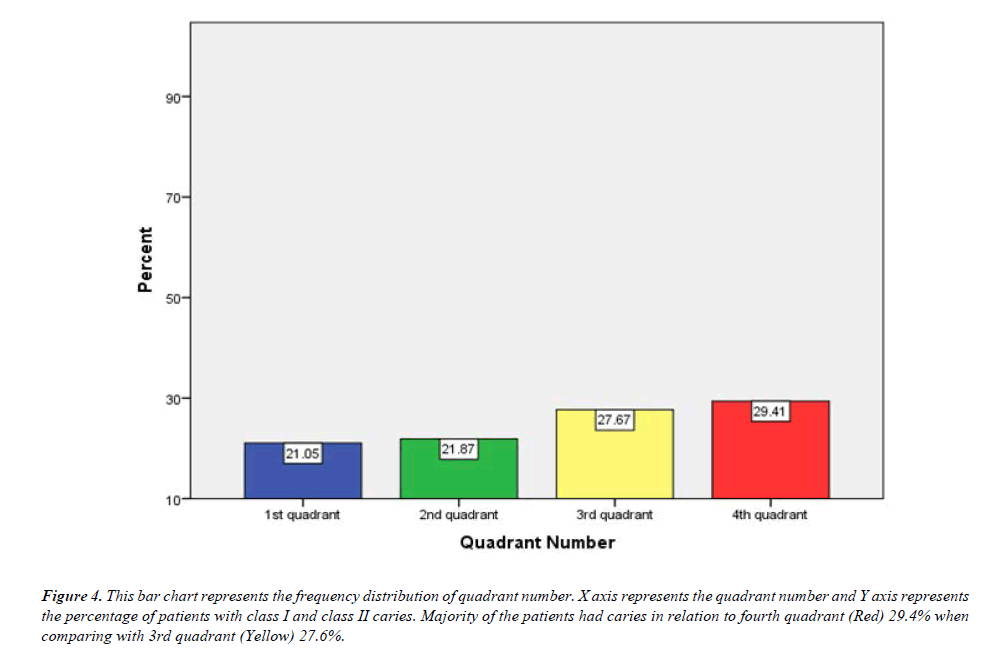

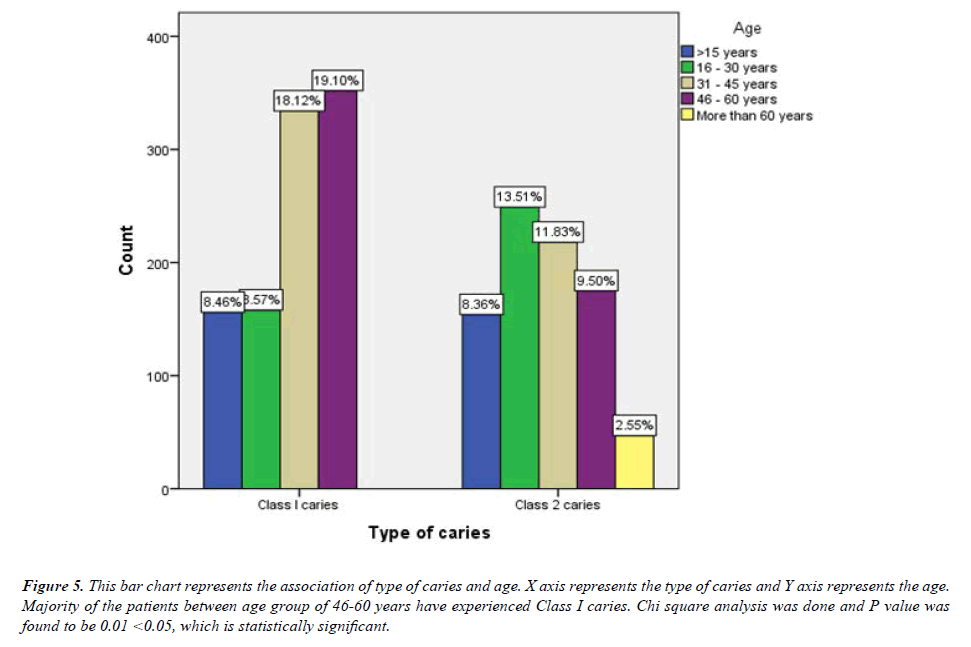

The results of the study are presented as bar diagrams below. Figure 1 represents the frequency distribution of age group. Figure 2 represents the frequency distribution of gender. Figure 3 represents the frequency distribution of type of caries. Figure 4 represents the frequency distribution of quadrant number. Figure 5 represents the association of type of caries and age. Figure 6 represents the association between the type of caries and gender.

Figure 1: This bar chart represents the frequency distribution of age group. X axis represents the age group and Y axis represents the percentage of patients with class I and class II caries. Majority of the patients were between the age group of 31-45 years (Yellow) 29.95 compared to 46-60 years (Red) 28.5%.

Figure 4: This bar chart represents the frequency distribution of quadrant number. X axis represents the quadrant number and Y axis represents the percentage of patients with class I and class II caries. Majority of the patients had caries in relation to fourth quadrant (Red) 29.4% when comparing with 3rd quadrant (Yellow) 27.6%.

Figure 5: This bar chart represents the association of type of caries and age. X axis represents the type of caries and Y axis represents the age. Majority of the patients between age group of 46-60 years have experienced Class I caries. Chi square analysis was done and P value was found to be 0.01 <0.05, which is statistically significant.

Figure 6:This bar chart represents the association between the type of caries and gender. X axis represents the type of caries and Y axis represents the gender. Majority of the male patients have experienced Class I (38.9%) whereas female patients have got Class II caries (23%). Chi square analysis was done and P value was found to be 0.00 < 0.05, which is statistically significant.

Discussion

From our current study it is seen that, majority of the participants who had class I and Class II caries were between the age group of 31-45 years (29.9%) followed by 46-60 year (28.5%), 16-30 years (22%), >15 years (16.8%) and more than 60 years (2.5%) which correlates with the study done by Celia et al., 201632. With increasing age, the prevalence of caries in primary teeth decreased and the prevalence of caries in permanent teeth increased. The highest caries restoration rate was observed in the 12-year-old age group for primary teeth and in the 25-35 year old age group for permanent teeth [33]. Tooth decay is prevalent among middle-aged and older adults. While tooth decay is related to preventable causes such as sugar consumption, fluoride usage, and access to dental care, disparities exist even when dental care is available, due in part to social determinants of health [34].

The findings from the current study proves that, around 61.6% of the male population are prone to more dental caries than female population (38.36%) which correlates with the study done by Shaffer et al. [35]. Sex differences in dental caries experience have also been widely observed, with most studies showing that women and girls are at higher risk and experience more carious lesions than do men and boys [36]. The factors that cause men to experience a greater burden of dental caries are not fully understood, and some of these factors may differ among populations. Possible explanations have been proposed, including earlier tooth eruption in males (and therefore increased time of exposure to cariogenic processes), differences in dietary behaviors, access and utilization of oral health care, hormonal and/or physiological differences, and characteristics of the dentition, tooth enamel, or saliva [36,37].

From our current study it is seen that, around 54.2% of the population had class I caries whereas 45.7% of the population had class II caries which correlated with the study done by Zubair et al. [38]. Class I caries include occlusal surface, buccal and lingual pits of posterior teeth and lingual surface of anterior teeth whereas Class II are involving proximal surface of posterior teeth [39]. As the food particles are more prone to damage the occlusal surfaces more than proximal surface, Class I caries are said to be more common among the general population [40]. Association between type of caries and age was done and P value was found to be 0.01 < 0.05, which is statistically significant.

From our current study it is seen that, majority of the caries have affected the 4th quadrant (29.4%) more than other quadrants. Association between the type of caries and gender was done and P value was found to be 0.00 < 0.05, which is statistically significant.

Conclusion

Within the limits of the current study it proven that, Class I caries are more prone to affect the general population than Class II caries. Dental caries prognosis depends on the health of the patient, maintenance of oral hygiene, and the extent and severity of dental caries. If the individual reports early signs of dental caries, a lesion may be reversed with a preventive method and minor dental intervention like remineralization of the initial lesion. If dental caries progresses to the moderate stage with loss of specific tooth structure, the tooth must be filled and rebuilt. Prognosis is also crucial for decisionmaking regarding whether ordinary restoration or extensive restorative treatment should take place. Extensive restoration should not occur when there is a chance that the prognosis will be poor for salvaging the tooth.

Acknowledgement

The authors would thank all the participants for their valuable support and authors thank the dental institution for the support to conduct.

Conflict of interest

Nil

Source of funding

The present project is supported/funded/sponsored by

• Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences, Saveetha Dental College and Hospitals, Saveetha University, Chennai, India

• Al Fajr index

References

- Curzon ME, Preston AJ. Risk groups: Nursing bottle caries/caries in the elderly. Caries Res. 2004;38(1):24-33.

- Kidd E, Fejerskov O. How does a caries lesion develop? In Essentials of Dental Caries. Oxford University Press 2016.

- Selwitz RH, Ismail AI, Pitts NB. Dental caries. Lancet. 2007;369(9555):51-59.

- Gonzalez-Gonzalez JM. Fractal structure of caries. Caries Res. 1997;31(3):186-188.

- Bruvo M, Ekstrand K, Arvin E, et al. Optimal drinking water composition for caries control in populations. J Dent Res. 2008;87(4):340-343.

- Jiyao L. Clinical Management of Dental Caries. Dent Caries. 2016;107-128.

- https://www.intechopen.com/books/1442

- https://academic.oup.com/book/41697

- Sheiham A. Dental caries affects body weight, growth and quality of life in pre-school children. Br Dent J 2006; 201:625.

- Xiao H. Dental caries: Disease burden versus its prevention. In Dental Caries. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg 2016;91-106.

- Tahmourespour A. Probiotics and the reduction of dental caries risk. Contempary Approach Dental Caries 2012;1:271-288.

- Muthukrishnan L. Imminent antimicrobial bioink deploying cellulose, alginate, EPS and synthetic polymers for 3D bioprinting of tissue constructs. Carbohydr Polym. 2021;260:117774.

- PradeepKumar AR, Shemesh H, Nivedhitha MS, et al. Diagnosis of vertical root fractures by cone-beam computed tomography in root-filled teeth with confirmation by direct visualization: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Endod. 2021;47(8):1198-214.

- Chakraborty T, Jamal RF, Battineni G, et al. A Review of Prolonged Post-COVID-19 Symptoms and Their Implications on Dental Management. Int J Environ Res Pub Health. 2021;18(10):5131.

- Muthukrishnan L. Nanotechnology for cleaner leather production: a review. Environ Chem Lett. 2021;19(3):2527-49.

- Teja KV, Ramesh S. Is a filled lateral canal–A sign of superiority?. J Dent Sci. 2020;15(4):562.

- Narendran K, MS N, SARVANAN A. Synthesis, Characterization, Free Radical Scavenging and Cytotoxic Activities of Phenylvilangin, a Substituted Dimer of Embelin. Ind J Pharm Sci. 2020;82(5):909-12.

- Reddy P, Krithikadatta J, Srinivasan V, et al. Dental caries profile and associated risk factors among adolescent school children in an urban South-Indian city. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2020;18(1):379-86.

- Sawant K, Pawar AM, Banga KS, et al. Dentinal Microcracks after Root Canal Instrumentation Using Instruments Manufactured with Different NiTi Alloys and the SAF System: A Systematic Review. App Sci. 2021;11(11):4984.

- Bhavikatti SK, Karobari MI, Zainuddin SL, et al. Investigating the antioxidant and cytocompatibility of Mimusops elengi Linn extract over human gingival fibroblast cells. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(13):7162.

- Karobari MI, Basheer SN, Sayed FR, et al. An in vitro stereomicroscopic evaluation of bioactivity between Neo MTA Plus, Pro Root MTA, BIODENTINE & glass ionomer cement using dye penetration method. Material. 2021;14(12):3159.

- Rohit Singh T, Ezhilarasan D. Ethanolic extract of Lagerstroemia Speciosa (L.) Pers., induces apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in HepG2 cells. Nutr Cancer. 2020;72(1):146-56.

- Ezhilarasan D. MicroRNA interplay between hepatic stellate cell quiescence and activation. European J Pharmacol. 2020;885:173507.

- Romera A, Peredpaya S, Shparyk Y, et al. Bevacizumab biosimilar BEVZ92 versus reference bevacizumab in combination with FOLFOX or FOLFIRI as first-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer: a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lan Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;3(12):845-55.

- Raj RK. ß-Sitosterol-assisted silver nanoparticles activates Nrf2 and triggers mitochondrial apoptosis via oxidative stress in human hepatocellular cancer cell line. J Biomed Mat Res Part A. 2020;108(9):1899-1908.

- Vijayashree Priyadharsini J. In silico validation of the non-antibiotic drugs acetaminophen and ibuprofen as antibacterial agents against red complex pathogens. J Periodontol. 2019;90(12):1441-8.

- Priyadharsini JV, Girija AS, Paramasivam A. In silico analysis of virulence genes in an emerging dental pathogen A. baumannii and related species. Arch Oral Biol. 2018;94:93-8.

- Uma Maheswari TN, Nivedhitha MS, Ramani P. Expression profile of salivary micro RNA-21 and 31 in oral potentially malignant disorders. Braz Oral Res. 2020;10;34.

- Gudipaneni RK, Alam MK, Patil SR, et al. Measurement of the maximum occlusal bite force and its relation to the caries spectrum of first permanent molars in early permanent dentition. J Clin Pediatric Dent. 2020;44(6):423-8.

- Chaturvedula BB, Muthukrishnan A, Bhuvaraghan A, et al. Dens invaginatus: a review and orthodontic implications. B Dent J. 2021;230(6):345-50.

- Kanniah P, Radhamani J, Chelliah P, et al. Green synthesis of multifaceted silver nanoparticles using the flower extract of Aerva lanata and evaluation of its biological and environmental applications. Chemistry Select. 2020;5(7):2322-31.

- Hybels CF, Wu B, Landerman LR, et al. Trends in decayed teeth among middle-aged and older adults in the United States: socioeconomic disparities persist over time. J Pub Health Dent. 2016 Sep;76(4):287-94.

- Hybels CF, Wu B, Landerman LR, et al. Trends in decayed teeth among middle-aged and older adults in the United States: Socioeconomic disparities persist over time. J Public Health Dent 2016;76(4):287-94.

- Baskran RR, Ranjan M. Knowledge and awareness about class II dental caries among dental practitioners among the south Indian population. Int J Pharma Res. 2022;14(3).

- Shaffer JR, Leslie EJ, Feingold E, et al. Caries experience differs between females and males across age groups in Northern Appalachia. Int J Dent. 2015;2015.

- Dye BA, Tan S, Smith V, et al. Trends in oral health status; United States, 1988-1994 and 1999-2004.

- National Research Council, Division on Earth and Life Studies, Commission on Life Sciences, et al. Diet and health: Implications for reducing chronic disease risk. National Academies Press 1989.

- Zubair NH, Sukartini E, Hayati AT. The comparison of secondary caries between class I amalgam and class I composite restoration. Padjadjaran J Dent. 2010;22(3).

- Svanberg M. Class II amalgam restorations, glass-ionomer tunnel restorations, and caries development on adjacent tooth surfaces: a 3-year clinical study. Caries Res. 1992;26(4):315-7.

- Formann AK. Measurement errors in caries diagnosis: some further latent class models. Biometrics. 1994:865-71.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref