Research Article - Journal of Public Health and Nutrition (2022) Volume 5, Issue 4

Assess the magnitude of under nutrition and associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care service in public hospitals of Western Ethiopia.

Haile Bikila*

Department of Public Health, Wollega University, Nekemte, Western Ethiopia

- *Corresponding Author:

- Bikila H

Department of Public Health

Wollega University

Nekemte

Western Ethiopia

E-mail: haile.bikila@gmail.com

Received: 23-Dec-2021, Manuscript No. AAJPHN-21-50525; Editor assigned: 27-Dec-2021, Pre QC No. AAJPHN-21-50525(PQ); Reviewed: 11-Jan-2022, QC No. AAJPHN-21-50525; Revised: 11-Apr-2022, Manuscript No. AAJPHN-21-50525(R); Published: 18-Apr-2022, DOI: 10.35841/aajphn-5.4.116

Citation: Bikila H. Assess the magnitude of under nutrition and associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care service in public hospitals of Western Ethiopia. J Pub Health Nutri. 2022;5(4):116

Abstract

Background: Pregnancy is a time when the body is under a lot of stress, which increases your dietary needs. Under nutrition is a worldwide health issue, especially among pregnant women. Malnutrition during pregnancy can result in miscarriages, fetal deaths during pregnancy, preterm delivery, and maternal mortality for both the mother and her fetus. Therefore, this research was aimed to assess the magnitude of under nutrition and associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care services at public hospitals at Western Ethiopia. Objective: To assess the magnitude of under nutrition and associated factors among pregnant women attending Antenatal Care service in Public Hospitals of western Ethiopia. Methods: Facility based cross-sectional study was conducted from April 10 to May 10, 2020 among 780 pregnant mothers. The study participants were selected by systematic random sampling methods from antenatal care clinics of the hospitals. Interviewer administered structured questionnaire was used to collect the data and Mid-upper arm circumference, height and weight were measured to determine the magnitude of under nutrition among the study participants. The data were entered to Epi Info version 7.2.3, and then exported to SPSS version 24 for analysis. Multivariable logistic regression was used to identify independent predictors considering Adjusted Odd Ratio (AOR) at p-value ≤ 0.05 to measure the strength of association between dependent and independent variables. Result: The magnitude of under nutrition among pregnant women was found to be 39.2% (95%CI: 35.7%, 42.6%). Rural residence [(AOR=1.97, 95% CI: (1.24, 3.14)], substance use [(AOR: 3.33, 95% CI: (1.63, 6.81)], low dietary diversity of women [(AOR= 7.56, 95% CI: (4.96, 11.51)], mildly food insecure household [(AOR= 4.36, 95% CI: (2.36, 8.79)], moderately food insecure household [(AOR= 3.71, 95%CI: (1.54, 8.79), and severely food insecure household [(AOR= 6.96, 95% CI: (3.15, 15.42)] were factors significantly associated with under nutrition. Conclusion: The study showed that the magnitude of under nutrition is very high among pregnant women. Factors associated with under nutrition of pregnant women were rural residency, household food insecurity, dietary diversity and substance use. Therefore, all concerned bodies should made efforts to reduce the risk of under nutrition by reducing substance use and improving household food security there by to increase women’s dietary diversity.

Keywords

Under nutrition, Pregnancy, Associated factor.

Abbreviations

ANC: Antenatal Care; AOR: Adjusted Odds Ratio; COR: Crude Odds Ratio; DALYs: Disability Adjusted Life Years; FAO: Food And Agricultural Organization; FFQ: Food Frequency Questionnaire; GDP: Gross Domestic Product; GHI: Global Hunger Index; HFIAS: Household Food Insecurity Access Scale; MCH: Maternal And Child Health; MDDW: Minimum Dietary Diversity Of Women; MUAC: Mid Upper Arm Circumference; SDGs: Sustainable Development Goals; UN: United Nations; UNICEF: United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund; USA: United States of America; WHO: World Health Organization

Background

Under nutrition is the result of inadequate intake of food in terms of either quantity or quality, poor utilization of nutrients due to infections or other illnesses, or a combination of these immediate causes [1]. Pregnancy strongly depends on the health and nutritional status of women and a high proportion of pregnant women are affected by poor nutrition which leads them to unhealthy and distress conditions. Under nutrition goes beyond calories and signifies deficiencies in any or all of the following: energy, protein, and/or essential vitamins and minerals [2].

Pregnancy constitutes states of considerable physiological stress, which cause increased nutritional demands. If these demands are in adequate, not only the nutritional status of the subject will affect, but also the course of pregnancy and lactation. Nutrition-related problems form the core of many current issues in women’s health, and poor nutrition can have profound effects on reproductive outcomes [3]. Lack of adequate nutrition of good quality and quantity during pregnancy can cause health problems for both the mother and her fetus. Under nutrition is among the most common causes of maternal mortality [1,4].

The prevalence of undernourishment-the percentage of the population without regular access to adequate calories-has stagnated since 2015, and the number of people who are hungry has actually risen to 822 million from 785 million in 2015 [1]. Expectant and nursing mothers, infants and children constitute the most vulnerable segments of a population from the nutritional standpoint. The Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 identified that maternal and child malnutrition causes 1.7 million deaths and 176.9 million DALYs (Disability Adjusted Life Years) [5]. A survey carried out in South India revealed that among poor women whose dietaries during pregnancy provided 1400-1500 calories and about 40 g of protein daily, nearly 20% of pregnancies had terminated in abortions, miscarriages or stillbirths [6].

Maternal under nutrition directly or indirectly causes about 3.5 million deaths of women in developing countries [7]. In developing countries, it has been estimated that poor nutritional status in pregnancy accounts for 14% of fetuses with IUGR (Intra Uterine Growth Retardation), and maternal stunting account for a further 18.5% [8]. If adolescents or women are undernourished during pregnancy, the cycle of maternal malnutrition, fetal growth restriction, child stunting, subsequent lifetime of impaired productivity, and increased maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality are continued [9].

Under nutrition among women in reproductive age is significantly higher in Africa due to chronic energy and/ or micronutrient deficiencies especially during pregnancy [10,11]. In developing nations the prevalence of under nutrition among pregnant women ranges from 13% to 38% [12,13]. The situation is worse in Africa that the burden of malnutrition among pregnant women is about 23% [14].

A 2018 WHO (World Health Organization) African region report indicates, nine countries in Africa had a prevalence rates above 15%, this includes Ethiopia in which maternal underweight exceeds 20% [15]. Recent study done among young pregnant mothers in Ethiopia indicates the prevalence of under nutrition is 38% [16]. Individual studies across Ethiopia indicates high rates of under nutrition among pregnant women, ranging from 9.2% to 44, 9% [17-24], making Ethiopia to be one of the countries with highest burden of maternal under nutrition from the world.

Malnutrition is holding back development with unacceptable human consequences [1]. Globally, hunger and malnutrition reduce a Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of a given country by 1.4-2.1 trillion United States Dollar (USD) a year. Similarly, malnutrition costs between 3 and 16% annual GDP of the 54 African countries, and for mentioning Ethiopia loss 16.5% a year [25,26].

Despite efforts made to improve the problem; the progress made in last decade was very low, and currently the burden of under nutrition is continued to be the major public health problem in developing countries including our country Ethiopia [3]. Different studies done across our country tried to show the burden and determinant of under nutrition among pregnant women, in any consideration of the problems of under nutrition, these segments require special consideration. As under nutrition caused by complex interrelated factors the programs and interventions designed to reduce its burden should depend on the reliable and recent information derived from extensive studies targeting this segment of population. Therefore, this study intended to provide valuable information to contribute to existing knowledge on the nutritional status of pregnant women at national and local level.

Materials and Methods

Study design, area, and period

An institution-based cross-sectional study design was carried out. This study was conducted in public general hospitals of the Oromia region. The study was conducted in five public hospitals in the zone were the selected study area. This study was conducted in Public Hospitals of western Ethiopia from April 10 to May 10, 2020.

Source and Study population

The source populations were all third-trimester pregnant women who were coming for delivery and antenatal care visits in the selected public general hospitals of the Oromia region. Third-trimester pregnancy women who were coming for antenatal care visits in general public hospitals of the Oromia region western part were selected as the study population.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All selected third-trimester pregnant women who were coming for ANC in public general hospitals during the study period were included, whereas pregnancy women with bilateral edema, who were seriously sick and unable to respond to the interview, were excluded from the study.

Sample size and Sampling techniques

Sample size was calculated using double population proportion formula by assuming precision OR (Odd ratio) 1.52 (d) =5%, confidence level =95% (Ζα/2=1.96), and proportion of under nutrition (P1 proportion among exposed group) 49.5%, (p2 proportion among exposed group) 39.2%. By, it becomes 768. By considering a 5% non-response rate, 806 pregnant women were taken as a final sample size after using the design effect two.

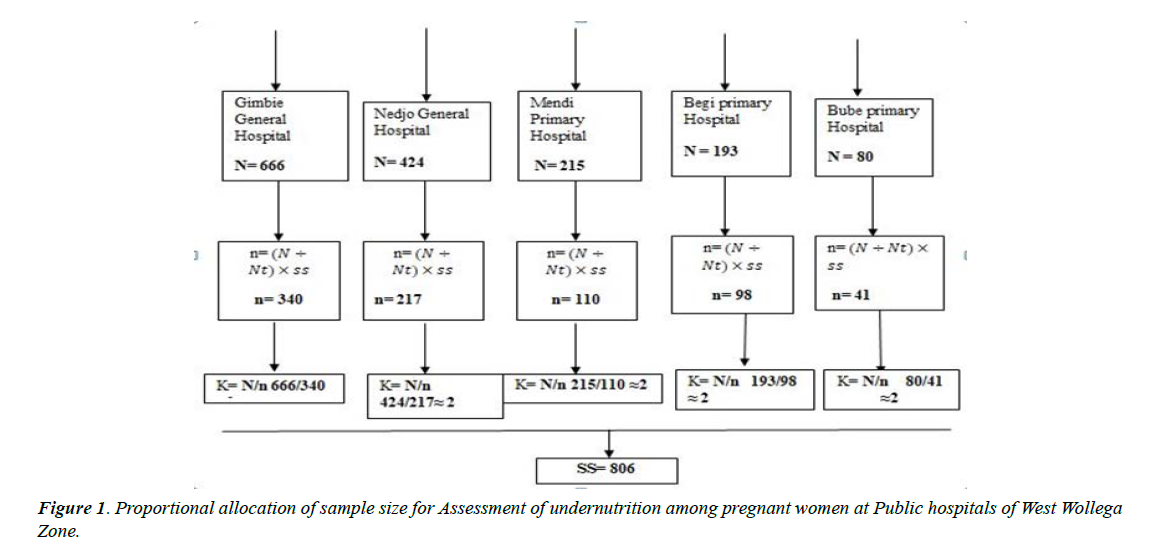

The sample size was allocated proportional to their average monthly client flow. Systematic sampling was used to select the study units from pregnant women attending ANC. The interval K value was determined for samples at each hospital by dividing the number of units in the population (N) by the desired sample size (n). The first respondent selected by lottery method, and then every second respondent was included until the desired sample size was attained (Figure 1).

Data collection procedure

A semi-structured questionnaire was initially prepared in English and then translated into the regional language; Afaan Oromo was used. Afaan Oromo version was again translated back to English to check for any inconsistencies or distortion in the meaning of words. Data were collected using an interviewer-administered, and MUAC measurement questionnaire was adapted from the literature. Data collection was performed by one BSc Nurse as supervisor and five Midwifery nurses (Diploma) were employed for data collection. To assure the quality of the data properly designed data collection instrument and training of data collectors and supervisors was done, the enumerators and the supervisor were given training for three days on procedures, techniques, ways of collecting the data, and monitoring the procedure especially on anthropometric measurement. Ten percent pretest was done at the, Gida public general hospital to check the consistency of the questioner. The collected data were reviewed and checked for completeness by supervisors and principal investigators each week. MUAC was measured by considering the mothers in Frankfurt plane and sideways to measure the left side, arms hanging loosely at the side with the palm facing inward, taken at marked midpoint of upper left arm, a flexible non stretchable tape were used, and difference between trainee and trainer was 0-5 mm after standardization of measurement error calculation before data collection.

Independent and dependent variable

Nutritional status of pregnant mothers is the outcome variable, and the independent variables were all the sociodemographic characteristics, dietary habit, environmental, maternal obstetrical and gynecology history. A brief description of how some of these variables were measured is as follows.

Dependent variable

The mid-upper arm circumstance values below a cutoff point <23 cm were considered as under nutrition in this study, whereas for the individual 23 cm and above, was considered normal [13].

Potential confounding factor

Potential confounding variables measured in the study were socio-demographic characteristics, obstetrics and gynecology including the age of mother, marital status, religion, educational background of mothers, women’s decision-making autonomy, household income, occupation, ethnicity, number of antenatal care visits, type of pregnancy, maternal previous surgery, malaria, parity, iron and folic acid supplementation, marriage at age, substance use, hemoglobin level, coffee intake, husband’s support, difficulty to access food during the last three months, Dietary diversity, household food insecurity, prenatal feeding habits like skipping meals, frequency of meal, habit of eating snack, food avoidance, and food intake and history of low birth weight.

Anthropometric measurement

The anthropometric measurement mid upper arm circumstance was taken from individual third-trimester pregnant women. Intra-observer and inter-observer variability of anthropometric measurement were assessed on 10 volunteers to reduce Technical Error of Measurement (TEM) at end of training. The measuring instruments were calibrated after each session of measurements. The Supervisor gave close supervision and technical supports, and checked the collected data for completeness, accuracy, and consistency every day and onsite.

Results

Socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of pregnant women

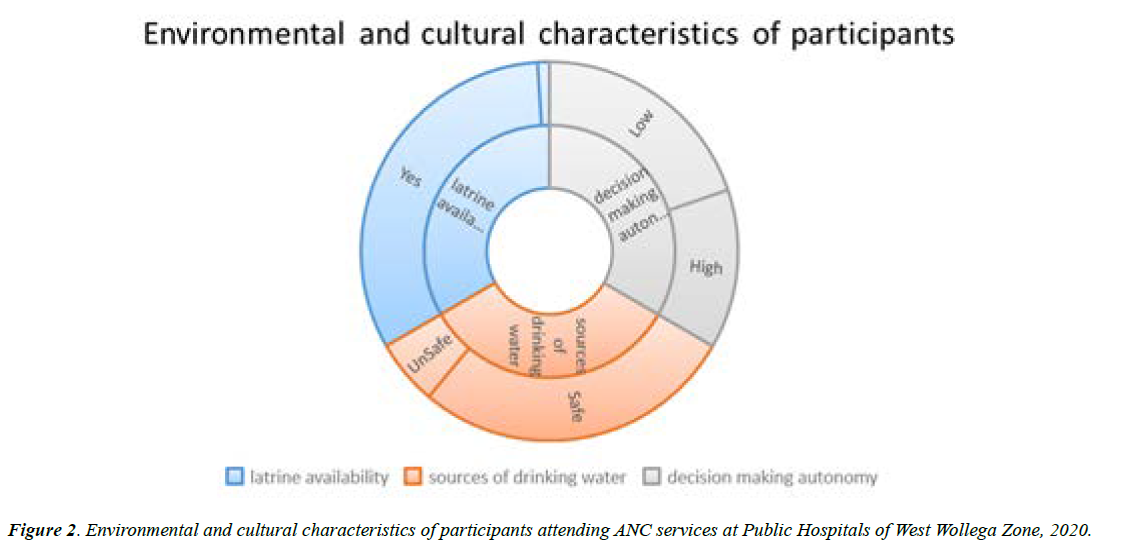

Out of 806 pregnant initially planned to be included in the study, 780 of them were participated with 96.8% response rate. The mean (± SD) age of respondents was 26 ± 5.32. The median family size of respondents was three persons. Majorities (64.7%) of respondents were Protestant, and about 20% were Orthodox follower. All most all of the participants (97.7% were married. Majority (53.1%) of respondents are urban dwellers while the rest (46.9%) are rural residents. About 24% of respondents completed tertiary education while only 8% had no formal education. Nearly half (48.6%) of participants were Housewife, and only 6.4% of them were daily laborers. Majority (55.4%) of respondent’s family have >1500 ETB monthly income (Table 1). Nearly all 96.7% of participants have latrine near their house, while 83.7% have access to safe water source, and Fifty nine percent of pregnant women have low decision-making autonomy while the rest have high decision-making autonomy (Figure 2).

| Variables | Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Religion of respondents | Muslim | 72 | 9.2 |

| Protestant | 505 | 64.7 | |

| Orthodox | 158 | 20.3 | |

| Others | 45 | 5.8 | |

| Marital status of respondents | Single | 12 | 1.5 |

| Married | 762 | 97.7 | |

| Divorced | 6 | 0.8 | |

| Residence | Urban | 414 | 53.1 |

| Rural | 366 | 46.9 | |

| Respondents occupational status | Government employee | 151 | 19.4 |

| Merchant | 118 | 15.1 | |

| House wife | 379 | 48.6 | |

| Daily laborer | 50 | 6.4 | |

| Student | 82 | 10.5 | |

| Couples occupational status | Government employee | 182 | 23.7 |

| Farmer | 253 | 32.9 | |

| Merchant | 134 | 17.4 | |

| Daily laborer | 199 | 25.9 | |

| Age group of respondents | 15-24 | 330 | 42.3 |

| 25-34 | 396 | 50.8 | |

| 35-49 | 54 | 6.9 | |

| Respondents educational status | No formal education | 60 | 7.7 |

| Primary education | 282 | 36.2 | |

| Secondary education | 252 | 32.3 | |

| Tertiary education | 186 | 23.8 | |

| Couples educational status | No formal education | 54 | 7 |

| Primary education | 246 | 32 | |

| Secondary education | 294 | 38.3 | |

| Tertiary education | 174 | 22.7 | |

| Family size of respondent | =3 | 486 | 62.3 |

| 04-Jun | 240 | 30.8 | |

| >6 | 54 | 6.9 | |

| Presence of under five children in the house hold | No | 456 | 58.5 |

| Yes | 324 | 41.5 | |

| Household monthly income | <1000 | 246 | 31.5 |

| 1000-1500 | 102 | 13.1 | |

| >1500 | 432 | 55.4 | |

| Note: Others* 7th day Adventists | |||

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of participants attending Antenatal care services at Public Hospitals of West Wollega Zone, 2020

Reproductive and health care characteristics of the respondents

A mean (± SD of age at first marriage, number of pregnancy, and gestational age of respondents were 19(± 2.14) years, 2 (± 1.16) pregnancy, and 30 (± 5.1) weeks respectively. About three fourth of participants were married at age of 18 years and above. Majority (63.8%) of respondents were at their third trimesters of pregnancy, about two third 68.5 of them were multigravida. Seven hundred and two of respondents (90%) said their current pregnancy was intended. About 78% of respondents were used any type of contraceptive before current pregnancy. One hundred fifty six (20%) of respondents reported history of pregnancy related complication, 8.5% reported history of current illness, and 3.8% reported history of chronic illness, while only 6.3% of them have history of substance use(Table 2).

| Variables | Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at first marriage of respondents (N=774) | <18 years | 132 | 17.1 |

| = 18 years | 642 | 82.9 | |

| Trimesters of pregnancy | Second | 282 | 36.2 |

| Third | 498 | 63.8 | |

| Number of pregnancy | Prim gravida | 246 | 31.5 |

| Multigravida | 534 | 68.5 | |

| Number of birth (N=528) | Null para | 276 | 52.3 |

| Multipara | 252 | 47.7 | |

| Previous birth interval (N=252) | <2 years | 30 | 11.9 |

| 2 to 4 years | 150 | 59.5 | |

| >= 4 years | 72 | 28.6 | |

| Intention of current pregnancy | No | 78 | 10 |

| Yes | 702 | 90 | |

| Number of antenatal care visit | First visit | 210 | 26.9 |

| Second visit | 216 | 27.7 | |

| Third visit | 210 | 26.9 | |

| Fourth visit | 144 | 18.5 | |

| Previous contraceptive use | No | 174 | 22.3 |

| Yes | 606 | 77.7 | |

| Nutritional advice during pregnancy (N=570) | No | 276 | 48.4 |

| Yes | 294 | 51.6 | |

| Use of iron and folic acid supplementation (N=570) | No | 36 | 6.3 |

| Yes | 534 | 93.7 | |

| Deworming (N=570) | No | 473 | 83 |

| Yes | 97 | 17 | |

| History of pregnancy complication | No | 624 | 80 |

| Yes | 156 | 20 | |

| History of current illness | No | 714 | 91.5 |

| Yes | 66 | 8.5 | |

| History of frequent illness | No | 708 | 90.8 |

| Yes | 72 | 9.2 | |

| History of chronic illness | No | 750 | 96.2 |

| Yes | 30 | 3.8 | |

| Substance use | No | 731 | 93.7 |

| Yes | 49 | 6.3 | |

Table 2. Reproductive and medical characteristics of participants attending Antenatal care services at Public Hospitals of West Wollega Zone, 2020 (N=780)

Dietary characteristics of the respondents

Two hundred and thirty six (30.3%) of participants respond as consuming meals less than three times a day while majority of respondents (62.3%) of them said not increased their meals since pregnancy. Nearly half (49.2%) of pregnant women reported no habit of eating snack. Only 14.6% of participants have habit of fasting, while 18.5% have food avoidance and 8.5% have habit of skipping meal during current pregnancy.

More than three forth (80%) of pregnant women have poor prenatal feeding habit, 40% of them consumed low dietary diversity. From total participants, 600 (76.9%) were from food secure, 10.8% were from mildly food insecure, 5.4% were from moderately food insecure, and 6.9% were from severely food insecure household (Table 3). All most all (97.7%) of the participants adequately consume cereals, more than three forth (80.1%) adequately consume legumes, and more than half (58.3%) adequately consume dark green leafy vegetables. Less than half of respondents adequately consume the rest of food group listed in the table below, except milk and its products, which no participants have adequately consumed during last four weeks before the study (Table 4).

| Variables | Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of meals in a day | <3 | 236 | 30.3 |

| =3 | 544 | 69.7 | |

| Increased frequency of meals | No | 486 | 62.3 |

| Yes | 294 | 37.7 | |

| Habit of eating snack | No | 384 | 49.2 |

| Yes | 396 | 50.8 | |

| Habit of fasting | No | 666 | 85.4 |

| Yes | 114 | 14.6 | |

| Food avoidance | No | 636 | 81.5 |

| Yes | 144 | 18.5 | |

| Habit of skipping meal | No | 714 | 91.5 |

| Yes | 66 | 8.5 | |

| Prenatal feeding habits of respondents | Poor | 630 | 80.8 |

| Good | 150 | 19.2 | |

| Dietary diversity of woman | Low | 312 | 40 |

| High | 468 | 60 | |

| Household food insecurity status | Food secure | 600 | 76.9 |

| Mild | 84 | 10.8 | |

| Moderate | 42 | 5.4 | |

| Severe | 54 | 6.9 | |

Table 3. Prenatal feeding habits of participants attending Antenatal care services at Public Hospitals of West Wollega Zone, 2020

| Variable | Category | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cereals intake | Inadequate | 18 | 2.3 |

| Adequate | 762 | 97.7 | |

| Legumes intake | Inadequate | 155 | 19.9 |

| Adequate | 625 | 80.1 | |

| Dark green leafy vegetables intake | Inadequate | 325 | 41.7 |

| Adequate | 455 | 58.3 | |

| Yellow orange vegetables intake | Inadequate | 522 | 66.9 |

| Adequate | 258 | 33.1 | |

| White roots and tubers intake | Inadequate | 532 | 68.2 |

| Adequate | 248 | 31.8 | |

| Flesh meats intake | Inadequate | 696 | 89.2 |

| Adequate | 84 | 10.8 | |

| Milk and milk products intake | Inadequate | 768 | 98.5 |

| Adequate | 12 | 1.5 | |

| Eggs intake | Inadequate | 672 | 86.2 |

| Adequate | 108 | 13.8 | |

| Oils and fats intake | Inadequate | 522 | 66.9 |

| Adequate | 258 | 33.1 |

Table 4. Consumption of common food groups among participants attending ANC services at Public Hospitals of West Wollega Zone, 2020

Nutritional status of respondents

The mean (± SD) MUAC of pregnant women studied was 24.24 (± 2.7) cm. The magnitude of under nutrition (MUAC <23 cm) was 39.2%, (95%CI: 35.7%, 42.6%) (Figure 3)

Results of logistic regression analysis: Under nutrition was taken as a dependent variable and compared against each independent variable for association. Bivariable logistic regression was done to identify factors associated with nutritional status of pregnant women. Accordingly, household food insecurity, low dietary diversity, poor prenatal feeding habits, number of pregnancy, trimesters of pregnancy, age at first marriage less than 18 years, family size ≥6, substance use, chronic illness, rural residence, not eating snack, not increase frequency of meal shows significant association with under nutrition crudely at 25% (Tables 5-7).

| Associated Factors | Undernutrition (MUAC<23) | P-Value | COR | 95%C.I for COR | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes Count (%) | No | Lower | Upper | ||||

| Count (%) | |||||||

| Age group of respondents | 15-24 | 138(41.8) | 192(58.2) | 0.717 | 0.89 | 0.5 | 1.6 |

| 25-34 | 144(36.4) | 252(63.6) | 0.251 | 0.71 | 0.4 | 1.27 | |

| 35-49 | 24(44.4) | 30(55.60) | 1 | ||||

| Respondents residence | rural | 198(54.1) | 168(45.9) | 0 | 3.34 | 2.47 | 4.51* |

| urban | 108(26.1) | 306(73.9) | 1 | ||||

| Household monthly income | <1000 | 112(47.5) | 124(52.5) | 0.263 | 1.29 | 0.79 | 5.25 |

| 1000-1500 | 46(45.1) | 56(54.9) | 0.156 | 1.17 | 0.54 | 3.98 | |

| >1500 | 178(41.2) | 254(58.8) | 1 | ||||

| Family size of respondent | >=6 | 30(55.6) | 24(44.4) | 0.039 | 1.82 | 1.03 | 3.20* |

| 04-May | 78(32.5) | 162(67.5) | 0.032 | 0.7 | 0.51 | 0.97 | |

| <=3 | 198(40.7) | 288(59.3) | 1 | ||||

| Presence of under five children | Yes | 138(42.6) | 186(57.4) | 0.105 | 0.79 | 0.59 | 1.05 |

| No | 168(36.8) | 288(63.2) | 1 | ||||

| Sources of drinking water | Unsafe | 48(80) | 12(20) | 0.479 | 1.15 | 0.78 | 1.68 |

| Safe | 258(35.8) | 462(64.20) | 1 | ||||

| No latrine | Yes | 12(50) | 12(50) | 0.276 | 1.57 | 0.7 | 3.54 |

| No | 294(38.9) | 462(61.1) | 1 | ||||

| Decision making autonomy | Low | 186(40.3) | 276(59.7) | 0.478 | 1.11 | 0.83 | 1.49 |

| High | 120(37.7) | 198(62.3) | 1 | ||||

| Substance use | Yes | 32(65) | 17(34.7) | 0 | 3.14 | 1.71 | 5.76* |

| No | 274(37.5) | 45762.5) | 1 | ||||

| Respondents educational status | No formal education | 66(55) | 54(45) | 0.528 | 1.21 | 0.67 | 2.2 |

| Primary education | 162(52.9) | 144(47.1) | 0.127 | 1.35 | 0.92 | 1.97 | |

| Secondary education | 66(28.9) | 162(71.1) | 0.576 | 1.12 | 0.75 | 1.66 | |

| Tertiary education | 12(9.5) | 114(90.5) | 1 | ||||

| Couples educational status | No formal education | 72(60) | 48(40) | 0.393 | 1.31 | 0.71 | 2.43 |

| Primary education | 108(50) | 108(50) | 0.425 | 0.85 | 0.57 | 1.27 | |

| Secondary education | 9638.1) | 156(61.9) | 0.141 | 1.33 | 0.91 | 1.96 | |

| Tertiary education | 30(16.7) | 150(83.3) | 1 | ||||

| Respondents occupational status | farmer | 66(45.8) | 78(54.2) | 0.258 | 1.33 | 0.81 | 2.17 |

| merchant | 18(25) | 54(75) | 0.867 | 1.03 | 0.7 | 1.53 | |

| house wife | 198(51.6) | 186(48.4) | 0.651 | 1.16 | 0.6 | 2.24 | |

| daily laborer | 18(33.3) | 36(66.7) | 0.099 | 1.58 | 0.92 | 2.73 | |

| government employee | 6(6.7) | 84(93.3) | 1 | ||||

| Couples occupational status | farmer | 192(56.1) | 150(43.9) | 0.094 | 1.4 | 0.94 | 2.06 |

| merchant | 18(15) | 102(85) | 0.551 | 1.15 | 0.73 | 1.82 | |

| daily laborer | 72(52.2) | 66(47.8) | 0.774 | 1.06 | 0.7 | 1.61 | |

| government employee | 24(14.8) | 138(85.2) | 1 | ||||

| Note: * = statistically significant at p-value < 0.25, 1: reference category, COR: Crude Odds Ratio, 95%CI: 95 percent confidence interval | |||||||

Table 5. Bivariate analysis of Socio demographic factors associated with undernutrition among pregnant women attending ANC at West Wollega public Hospitals, 2020

| Associated Factors | Undernutrition (MUAC<23) | P-Value | COR | 95% CI for COR | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes, Count (%) | No. Count (%) | Lower | Upper | ||||

| Number of pregnancy | multigravida | 228(42.7) | 306(57.3) | 0.004 | 1.61 | 1.17 | 2.21* |

| prim gravida | 78(31.7) | 168(68.3) | 1 | ||||

| Trimesters of pregnancy | 3rd trimester | 174(34.9) | 324(65.1) | 0.001 | 0.61 | 0.45 | 0.82* |

| 2nd trimester | 132(46.8) | 150(53.2) | 1 | ||||

| Age at first marriage | <18 years | 96(72.7) | 36(27.3) | 0 | 5.49 | 3.62 | 8.32* |

| >=18 years | 210(32.7) | 432(67.3) | 1 | ||||

| History of illness in current pregnancy | Yes | 30(45.5) | 36(54.5) | 0.28 | 1.32 | 0.8 | 2.2 |

| No | 276(38.7) | 438(61.3) | 1 | ||||

| History of chronic illness | Yes | 18(60) | 12(40) | 0.021 | 2.41 | 1.14 | 5.06* |

| No | 288(38.4) | 262(61.6) | 1 | ||||

| History of pregnancy complication | Yes | 60(38.5) | 96(61.5) | 0.826 | 0.96 | 0.67 | 1.38 |

| No | 246(39.40) | 378(60.60) | 1 | ||||

| No previous contraceptive use | Yes | 72(41.40) | 102(58.60) | 0.51 | 1.12 | 0.8 | 1.58 |

| No | 234(38.60) | 372(61.40) | 1 | ||||

| Number of antenatal care visit | first visit | 84(40) | 126(60) | 0.276 | 0.79 | 0.51 | 1.21 |

| second visit | 66(30.60) | 150(69.4) | 0.003 | 0.52 | 0.34 | 0.81 | |

| third visit | 90(42.9) | 120(57.1) | 0.58 | 0.89 | 0.58 | 1.36 | |

| fourth visit | 66(45.8) | 78(54.2) | 1 | ||||

| Non intended pregnancy | Yes | 36(46.2) | 42(53,8) | 0.188 | 1.37 | 0.86 | 2.2 |

| No | 270(38.5) | 432(61.5) | 1 | ||||

| Note: * = statistically significant at p-value <0.25, 1: reference category, COR: Crude Odds Ratio, 95%CI: 95 percent confidence interval | |||||||

Table 6. Bivariate analysis of Reproductive and medical factors associated with undernutrition among participants attending ANC services at West Wollega public Hospitals, 2020

| Associated Factors | Undernutrition (MUAC<23) | P-Value | COR | 95% CI for COR | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes, Count (%) | No, Count (%) | Lower | Upper | ||||

| Less than three meals in a day | Yes | 95(40.3) | 141(59.7) | 0.7 | 1.06 | 0.78 | 1.45 |

| No | 211(38.8) | 333(61.2) | 1 | ||||

| No habit of eating snack | Yes | 186(48.4) | 198(51.6) | 0 | 2.16 | 1.61 | 2.89* |

| No | 120(30.3) | 276(69.7) | 1 | ||||

| Not increased frequency of meals | Yes | 240(49.4) | 246(50.6) | 0 | 3.37 | 2.43 | 4.67* |

| No | 66(22.4) | 228(77.6) | 1 | ||||

| Food avoidance during pregnancy | Yes | 54(37.5) | 90(62.5) | 0.638 | 0.91 | 0.63 | 1.33 |

| No | 252(39.60) | 384(60.4) | 1 | ||||

| Habit of fasting while pregnant | Yes | 54(47.4) | 60(52.6) | 0.055 | 1.48 | 0.99 | 2.2 |

| No | 252(37.8) | 414(62.2) | 1 | ||||

| Habit of skipping meal | Yes | 54(81.8) | 12(18.2) | 0 | 8.25 | 4.33 | 15.71* |

| No | 252(35.3) | 462(64.7) | 1 | ||||

| Prenatal feeding habits | Poor | 187(29.7) | 443(70.3) | 0.236 | 0.84 | 0.25 | 1.67 |

| Good | 50(33.3) | 150(66.7) | 1 | ||||

| Household food insecurity status | Severe | 42(77.9) | 12(22.2) | 0 | 8.57 | 4.41 | 16.67* |

| Moderate | 30(71.4) | 12(28.8) | 0 | 6.12 | 3.06 | 12.23* | |

| Mild | 60(71.4) | 24(28.6) | 0 | 6.12 | 3.69 | 10.14* | |

| Food secure | 174(29) | 426(71) | 1 | ||||

| Dietary diversity of woman | Low | 222(71.2) | 90(28.8) | 0 | 11.28 | 8.03 | 15.84* |

| High | 84(17.9) | 384(82.0) | 1 | ||||

| Dark green leafy vegetables intake | inadequate | 121(37.2) | 204(62.8) | 0.334 | 0.87 | 0.65 | 1.16 |

| adequate | 185(40.7) | 270(59.3) | 1 | ||||

| Yellow orange vegetables intake | inadequate | 216(41.4) | 306(58.6) | 0.081 | 1.32 | 0.97 | 1.8 |

| adequate | 90(34.9) | 168(65.1) | 1 | ||||

| White roots and tubers intake | inadequate | 207(38.9) | 325(61.1) | 0.788 | 0.96 | 0.7 | 1.31 |

| adequate | 99(39.9) | 149(60.1) | 1 | ||||

| Flesh meats intake | inadequate | 270(38.8) | 426(61.2) | 0.472 | 0.85 | 0.53 | 1.34 |

| adequate | 36(42.9) | 48(57.1) | 1 | ||||

| Eggs intake | inadequate | 265(39.4) | 407(60.6) | 0.771 | 1.06 | 0.7 | 1.62 |

| adequate | 41(38) | 67(62.0) | 1 | ||||

| Oils and fats intake | inadequate | 202(38.7) | 320(61.3) | 0.664 | 0.94 | 0.69 | 1.27 |

| adequate | 104(40.3) | 154(59.7) | 1 | ||||

| Note: * = statistically significant at p-value <0.25, 1: reference category, COR: Crude Odds Ratio, 95%CI: 95 percent confidence interval | |||||||

Table 7. Bivariate analysis of dietary factors with nutritional status of pregnant women attending antenatal care clinics in public hospitals of west Wollega Zone, 2020

Variables associated with adjusted analysis: pregnant women, accordingly, household food insecurity, low dietary diversity, substance use and residence were identified as independent predictors of under nutrition among pregnant women.

The odds of under nutrition were four times [AOR=4.36, 95% CI: (2.36, 8.79)] more among mildly food insecure household, and nearly four times [AOR=3.71, 95% CI: 1.54, 8.61), among moderately food insecure households, and six times [AOR=6.96, 95% CI: (3.15,15.42)] among severely food insecure household) compared with their food secure counterparts. Pregnant women with low dietary diversity had seven times [AOR=7.56, 95% CI :( 4.96, 11.51)] increased odds of under nutrition than those with high dietary diversity status.

Moreover, the odds of under nutrition was three times [AOR=3.33, 95% CI: 1.63, 6.81)] among substance users -than their counter- parts. Rural pregnant women had nearly three times [AOR=2.68, 95%CI: 1.77, 4.06)] increased odds of under nutrition than urban women (Table 8).

| Associated factors | Undernutrition(MUAC<23cm) | Bivariate analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COR | 95% C.I COR | AOR | References -->

References

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref | ||||||