Research Article - Journal of Clinical Dentistry and Oral Health (2022) Volume 6, Issue 3

Retrospective analysis of incidence of dental caries in posterior teeth in males and females.

Azima Hanin S.M, Anjaneyulu K*Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics, Saveetha Dental College, Saveetha University, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India

- *Corresponding Author:

- Anjaneyulu K

Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics

Saveetha Dental College, Saveetha University

Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences

Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India

E-mail: kanjaneyulu.sdc@saveetha.com

Received: 21-Apr-2022, Manuscript No. AACDOH-22-61373; Editor assigned: 23-Apr-2022, PreQC No. AACDOH-22-61373 (PQ); Reviewed: 07-May-2022, QC No. AACDOH-22-61373; Revised: 10-May-2022, Manuscript No. AACDOH-22-61373 (R); Published: 17-May-2022, DOI:10.35841/aacdoh- 6.3.115

Citation: Azima HSM, Anjaneyulu K. Retrospective analysis of incidence of dental caries in posterior teeth in males and females. J Clin Dentistry Oral Health. 2022;6(3):115

Abstract

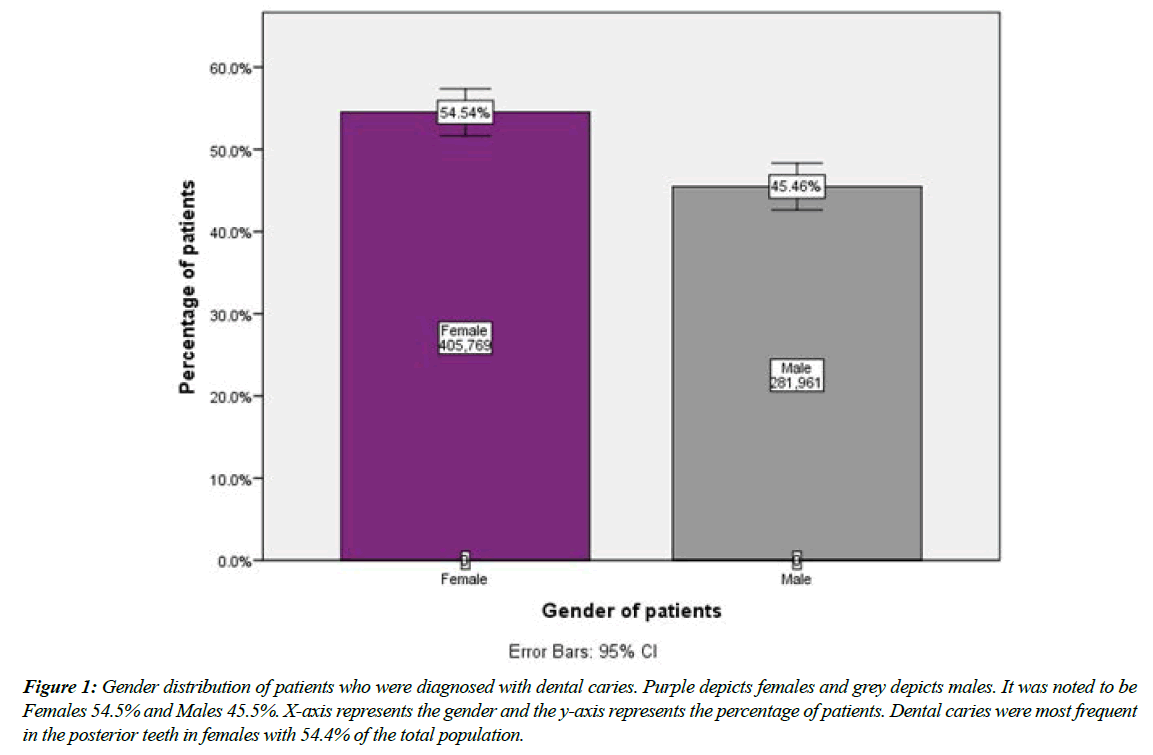

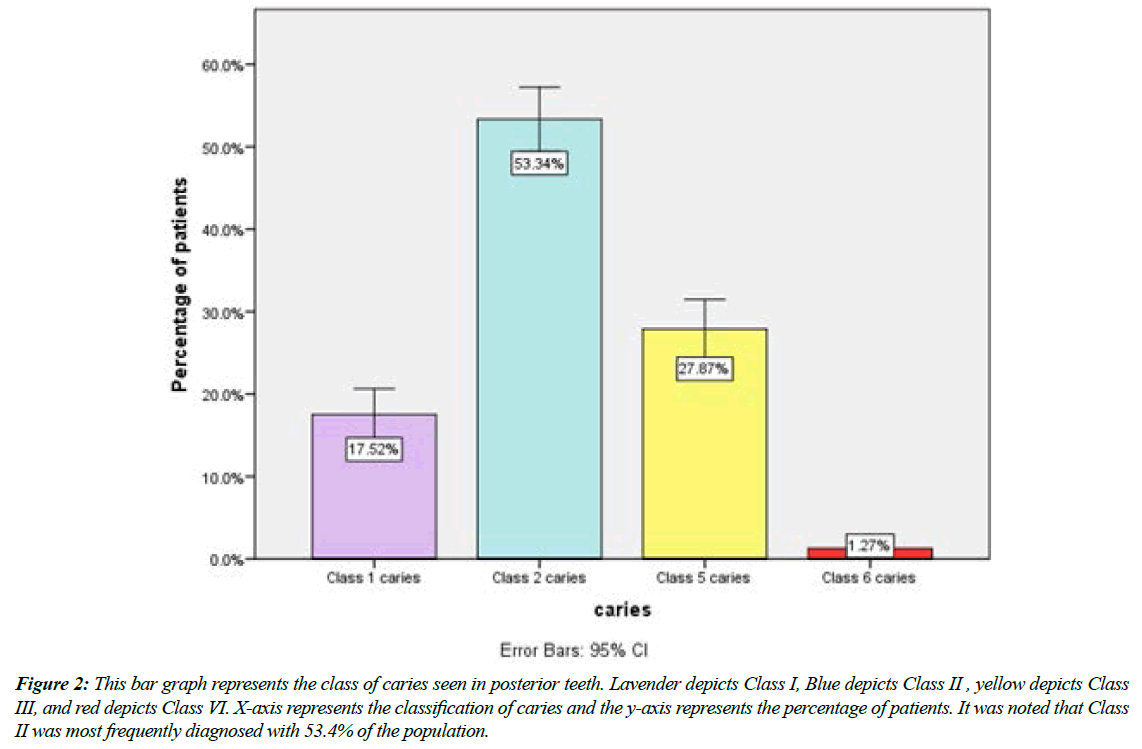

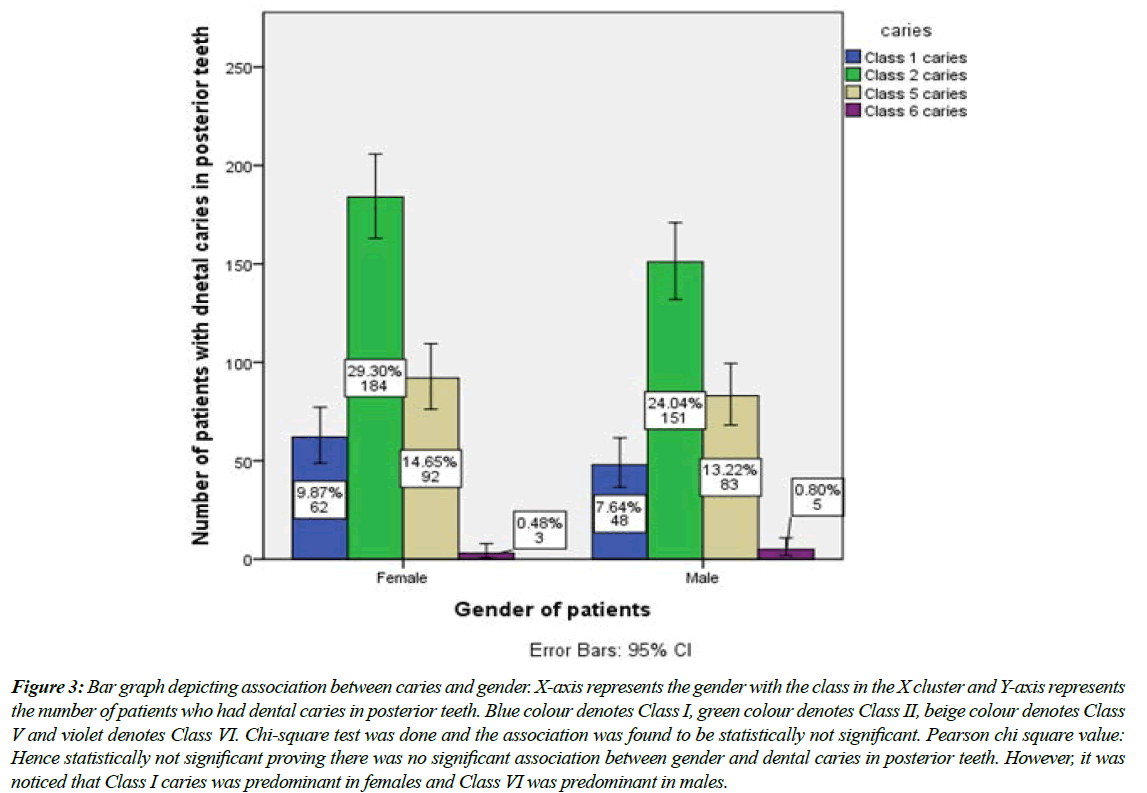

Introduction: Dental caries is a chronic disease which is considered to be a major public health problem globally. There is evidence indicating that many caries risk factors provide a gender bias due to such as different salivary composition and flow rate, hormonal fluctuations, dietary habits, genetic variations, and particular social roles among their family. Aim: The main objective of this study was to analyze the incidence of dental caries in posterior teeth in males and females. Materials and Methods: This retrospective study was conducted among patients who were diagnosed with dental caries in a university teaching hospital in Chennai during the period of December 2020 to May 2021. The collected data was then subjected to statistical analysis using Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS). Descriptive statistics and Chi square tests were used. Results: Dental caries were most frequent in the posterior teeth in females with 54.4% of the total population. It was noted that Class II was most frequently diagnosed with 53.4% of the population. It was noticed that Class I caries was predominant in females and Class VI was predominant in males. Conclusion: Within the limits of this study, it was observed that: 1. Dental caries were most frequent in the posterior teeth in females. 2. It was noted that Class II was most frequently diagnosed. 3. It was noticed that Class I caries was predominant in females and Class VI was predominant in males.

Keywords

Dental caries, Tooth diseases, Gender bias, Females, Males.

Introduction

Dental caries is a multifactorial disease that starts with microbiological shifts within the complex biofilm and is affected by salivary flow and composition, exposure to fluoride, consumption of dietary sugars, and by preventive behaviors (cleaning teeth) [1-4]. The disease is initially reversible and can be halted at any stage, even when some dentine or enamel is destroyed (cavitation), provided that enough biofilm can be removed [5-7]. Dental caries is a chronic disease that progresses slowly in most people. The disease can be seen in both the crown (coronal caries) and root (root caries) portions of primary and permanent teeth, and on smooth as well as pitted and fissured surfaces [8].

There is evidence indicating that many caries risk factors provide a gender bias, placing women at a higher caries risk than men [9]. These factors may include different salivary composition and flow rate, hormonal fluctuations, dietary habits, genetic vari- ations, and particular social roles among their family [10]. Additionally, there are systemic diseases that have been found to be associated with caries and to have an association with the female gender [11].

The issue of gender is controversial. In children, girls were found to have a higher risk for caries [12-14], whereas others have found it to be a modifier, [15] and yet others found boys to have a higher or similar risk [16]. In adults, white men have been found to be at a higher risk for root caries [17,18], whereas studies on other tooth surfaces have either found no effect of gender on caries risk or found women to be at a higher [16].

Some studies report about the gender differences in their findings and those that do, often show disparities. Some studies have stated a higher prevalence of tooth loss in women, whereas some studies showed a higher prevalence in men, while still others showed no significant relationship with gender [19- 26]. The variations could be because better dental behavior is seen among females due to better perception on esthetics and also women have a greater sensitivity towards illness and discomfort. In contrast women experience variations in estrogen and progesterone levels throughout their life cycle [27]. This is considered to make them more susceptible to periodontal disease than men [28]. Men on the other hand consume alcohol more often and smoke more cigarettes which make them more susceptible to tooth loss [28]. Our team has extensive knowledge and research experience that has translate into high quality publications [29-40].

Materials and Methods

Study Setting

This university hospital-based retrospective study was carried out by reviewing the dental records of patients diagnosed with dental caries who visited a university teaching hospital in Chennai. Since this was a university hospital setting the large sample size and distribution of population contributed a major advantage for this study. Data collected was reliable and with evidence. The study was conducted after obtaining approval from the Institutional Ethical Review Board.

Sampling

Data was reviewed and collected from 50,000 patient records over a one month period from December 2020. Data of those patients who were diagnosed with dental caries was collected. 1169 patients who were diagnosed with dental caries and in the age group of 1-60 years, were included in the study while those with incomplete hospital records were excluded from the study. Cross verification was done using photographs and radiographs.

Data collection

The following patient data were recorded as follows: hospital record number, gender, age, type of caries, radiographic/ dental diagnosis. The Total population of patients who were diagnosed with dental caries was 1169. Data collected was then exported to Microsoft Excel 2010.

Data analytics

The acquired data was subjected to statistical analysis. Microsoft Excel 2010 data spreadsheet was used for tabulation of parameters and later exported to the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS version 20.0) for Windows. Descriptive statistics were applied to the data and chi-square tests were applied at a level of significance of 5% (P < 0.05).

Results

Dental caries were most frequent in the posterior teeth in females with 54.4% of the total population (Figure 1). It was noted that Class II was most frequently diagnosed with 53.4% of the population (Figure 2). It was noticed that Class I caries was predominant in females and Class VI was predominant in males (Figure 3).

Figure 1: Gender distribution of patients who were diagnosed with dental caries. Purple depicts females and grey depicts males. It was noted to be Females 54.5% and Males 45.5%. X-axis represents the gender and the y-axis represents the percentage of patients. Dental caries were most frequent in the posterior teeth in females with 54.4% of the total population.

Figure 2: This bar graph represents the class of caries seen in posterior teeth. Lavender depicts Class I, Blue depicts Class II , yellow depicts Class III, and red depicts Class VI. X-axis represents the classification of caries and the y-axis represents the percentage of patients. It was noted that Class II was most frequently diagnosed with 53.4% of the population.

Figure 3: Bar graph depicting association between caries and gender. X-axis represents the gender with the class in the X cluster and Y-axis represents the number of patients who had dental caries in posterior teeth. Blue colour denotes Class I, green colour denotes Class II, beige colour denotes Class V and violet denotes Class VI. Chi-square test was done and the association was found to be statistically not significant. Pearson chi square value: Hence statistically not significant proving there was no significant association between gender and dental caries in posterior teeth. However, it was noticed that Class I caries was predominant in females and Class VI was predominant in males.

Discussion

Dental caries have been reported to disproportionately affect women in many populations all around the world. The magnitude of this disparity in dental caries by gender increases from childhood to adolescence and into adulthood. This difference was observed as early as 4000 BP. Surveys conducted in India, Hungary, Bangladesh, Spain, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and in isolated traditional Brazilian villages have reported higher caries rates in women than men [41-48]. Following a similar pattern as observed in caries, extraction in women is greater than in men and also has been linked to caries and parity [49]. Findings in this study corroborate with the above mentioned studies, it was noticed that dental caries were most frequent in the posterior teeth in females with 54.4% of the total population. There are suggestions that higher caries prevalence among women could be caused by easier access to food supplies and frequent snacking during food preparation and by behaviors related to access to dental care [41]. In certain countries, the gender difference in oral health seems to involve social and religious causes, such as son preference, ritual fasting, and dietary restrictions during pregnancy [44]. Genome-wide association studies have found caries susceptible and caries protective loci, some of which are X-linked, that influence variation in taste, saliva, and enamel proteins, affecting the oral environment and the microstructure of enamel, which may partly explain gender differences in caries. Because of the complexity of the data related to sociodemographic factors in caries risk assessment and management, they should be considered as a modifier or potential contributor to risk [45].

Class II carious lesions involve the proximal surfaces (mesial and distal) of posterior teeth with access established from the occlusal tooth surface. It was observed that Class II was most frequently diagnosed with 53.4% of the population, also Class I caries was predominant in females and Class VI was predominant in males. A study by Arshad Hassan et al had similar findings. The reason for prevalence of proximal caries may be due to the fact that deep seated debris and plaque inside the embrasures are often hard to clean with simple mechanical tooth brushing, whereas other classification sites are relatively easy to cleanse. Our study was the first of this kind that was done locally. Although local caries burden is known, studies on incidence of dental caries in posterior teeth in males and females are lacking.

Conclusion

Within the limits of this study, it was observed that:

1. Dental caries were most frequent in the posterior teeth in females.

2. It was noted that Class II was most frequently diagnosed.

3. It was noticed that Class I caries was predominant in females and Class VI was predominant in males.

References

- Pitts NB. Are we ready to move from operative to non-operative/preventive treatment of dental caries in clinical practice?. Caries Res. 2004;38(3):294-304.

- Featherstone JD. The science and practice of caries prevention. J Am Dent Assoc. 2000 Jul 1;131(7):887-99.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Oral health in America: a report of the Surgeon General. NIH Publ. 2000:155-88.

- Pitts NB. Modern concepts of caries measurement. J Den Res. 2004;83(1_suppl):43-7.

- Lukacs JR. Sex differences in dental caries experience: clinical evidence, complex etiology. Clin Oral Invest. 2011;15(5):649-56.

- Lukacs JR, Largaespada LL. Explaining sex differences in dental caries prevalence: Saliva, hormones, and “life‐history” etiologies. J Human Bio Ass. 2006;18(4):540-55.

- Krol DM. Dental caries, oral health, and pediatricians. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2003;33(8):253-70.

- Ismail AI, Sohn W, Lim S, et al. Predictors of dental caries progression in primary teeth. J Dent Res. 2009;88(3):270–5.

- Declerck D, Leroy R, Martens L, et al. Factors associated with prevalence and severity of caries experience in preschool children. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2008;36(2):168–78.

- Campus G, Lumbau A, Lai S, et al. Socio-economic and behavioural factors related to caries in twelve-year-old Sardinian children. Caries Res. 2001;35(6):427–34.

- Lukacs JR. Gender differences in oral health in South Asia: metadata imply multifactorial biological and cultural causes. Am J Hum Biol. 2011;23(3):398–411.

- Douglass CW, Jette AM, Fox CH, et al. Oral health status of the elderly in New England. J Gerontol. 1993;48(2):39–46.

- Joshi A, Douglass CW, Jette A, Feldman H. The distribution of root caries in community-dwelling elders in New England. J Public Health Dent. 1994;54(1):15–23.

- Hiidenkari T, Parvinen T, Helenius H. Edentulousness and its rehabilitation over a 10‐year period in a Finnish urban area. Comm Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1997;25(5):367-70.

- Nalçacı R, Erdemir EO, Baran I. Evaluation of the oral health status of the people aged 65 years and over living in near rural district of Middle Anatolia, Turkey. Arch Gerontol Geriat. 2007;45(1):55-64.

- Liu L, Zhang Y, Wu W, et al. Characteristics of dental care-seeking behavior and related sociodemographic factors in a middle-aged and elderly population in northeast China. BMC Oral Health. 2015 ;15(1):1-9.

- Ansai T, Takata Y, Soh I, A et al. Relationship between tooth loss and mortality in 80-year-old Japanese community-dwelling subjects. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:386.

- KraljevićŠimunković S, Vučićević Boras V, Pandurić J, et al. Oral health among institutionalised elderly in Zagreb, Croatia. Gerodontol. 2005;22(4):238-41.

- Suominen‐Taipale AL, Alanen P, Helenius H, et al. Edentulism among Finnish adults of working age, 1978–1997. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1999;27(5):353-65.

- Shah N. Gender issues and oral health in elderly Indians. Int Dental J. 2003;53(6):475-84.

- Sakki TK, Knuuttila ML, Vimpari SS, et al. Lifestyle, dental caries and number of teeth. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1994;22(5PT1):298-302.

- Kawamoto A, Sugano N, Motohashi M, Matsumoto S, Ito K. Relationship between oral malodor and the menstrual cycle. J Periodontal Res. 2010 Oct;45(5):681–7.

- Muthukrishnan L. Imminent antimicrobial bioink deploying cellulose, alginate, EPS and synthetic polymers for 3D bioprinting of tissue constructs. Carbo Poly. 2021;260:117774.

- PradeepKumar AR, Shemesh H, Nivedhitha MS, et al. Diagnosis of vertical root fractures by cone-beam computed tomography in root-filled teeth with confirmation by direct visualization: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Endo. 2021;47(8):1198-214.

- Chakraborty T, Jamal RF, Battineni G, et al. A review of prolonged post-COVID-19 symptoms and their implications on dental management. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(10):5131.

- Muthukrishnan L. Nanotechnology for cleaner leather production: a review. Environ Chem Lett. 2021;19(3):2527-49.

- Teja KV, Ramesh S. Is a filled lateral canal–A sign of superiority?. J Dent Sci. 2020;15(4):562.

- Narendran K, MS N, Sarvanan A. Synthesis, Characterization, Free Radical Scavenging and Cytotoxic Activities of Phenylvilangin, a Substituted Dimer of Embelin. Ind J Pharmac Sci. 2020;82(5):909-12.

- Reddy P, Krithikadatta J, Srinivasan V, et al. Dental caries profile and associated risk factors among adolescent school children in an urban South-Indian city. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2020;18(1):379-86.

- Sawant K, Pawar AM, Banga KS, et al. Dentinal Microcracks after Root Canal Instrumentation Using Instruments Manufactured with Different NiTi Alloys and the SAF System: A Systematic Review. App Sci. 2021;11(11):4984.

- Bhavikatti SK, Karobari MI, Zainuddin SL, et al. Investigating the Antioxidant and Cytocompatibility of Mimusops elengi Linn Extract over Human Gingival Fibroblast Cells. Int J Enviro Res Public Hea. 2021;18(13):7162.

- Karobari MI, Basheer SN, Sayed FR, et al. An In Vitro Stereomicroscopic Evaluation of Bioactivity between Neo MTA Plus, Pro Root MTA, BIODENTINE & Glass Ionomer Cement Using Dye Penetration Method. Mat. 2021;14(12):3159.

- Rohit Singh T, Ezhilarasan D. Ethanolic extract of Lagerstroemia Speciosa (L.) Pers., induces apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in HepG2 cells. Nutr Cancer. 2020;72(1):146-56.

- Ezhilarasan D. MicroRNA interplay between hepatic stellate cell quiescence and activation. Euro J Pharmacol. 2020;885:173507.

- Romera A, Peredpaya S, Shparyk Y, et al. Bevacizumab biosimilar BEVZ92 versus reference bevacizumab in combination with FOLFOX or FOLFIRI as first-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer: a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;3(12):845-55.

- Raj R K. β‐Sitosterol‐assisted silver nanoparticles activates Nrf2 and triggers mitochondrial apoptosis via oxidative stress in human hepatocellular cancer cell line. J Biomed Mat Res Part A. 2020;108(9):1899-908.

- Vijayashree Priyadharsini J. In silico validation of the non‐antibiotic drugs acetaminophen and ibuprofen as antibacterial agents against red complex pathogens. J Periodontol. 2019;90(12):1441-8.

- Priyadharsini JV, Girija AS, Paramasivam A. In silico analysis of virulence genes in an emerging dental pathogen A. baumannii and related species. Archiv Oral Biol. 2018;94:93-8.

- Uma Maheswari TN, Nivedhitha MS, Ramani P. Expression profile of salivary micro RNA-21 and 31 in oral potentially malignant disorders. Braz Oral Res. 2020;34.

- Gudipaneni RK, Alam MK, Patil SR, et al. Measurement of the maximum occlusal bite force and its relation to the caries spectrum of first permanent molars in early permanent dentition. J Clini Pediatr Dent. 2020;44(6):423-8.

- Chaturvedula BB, Muthukrishnan A, Bhuvaraghan A, et al. Dens invaginatus: a review and orthodontic implications. Br Dent J. 2021;230(6):345-50.

- Kanniah P, Radhamani J, Chelliah P, et al. Green synthesis of multifaceted silver nanoparticles using the flower extract of Aerva lanata and evaluation of its biological and environmental applications. Chem Select. 2020;5(7):2322-31.

- Griffin SO, Griffin PM, Swann JL, et al. New coronal caries in older adults: implications for prevention. J Dental Res. 2005;84(8):715-20.

- Petersen PE, Razanamihaja N. Oral health status of children and adults in Madagascar. Int Dent J. 1996;46(1):41-7.

- de Olivera Carrilho MR. Root caries: from prevalence to therapy. Karger Medi Sci Publ. 2017 Oct 19.

- Vieira AR. Genetic basis of oral health conditions. Springer. 2019.

- McGhee JR. Secretory Immunity and Infection: Proceedings of the International Symposium on the Secretory Immune System and Caries Immunity. Spri Sci Bus Med. 2012.

- Wu F, Zhu J, Li G, et al. Biologically synthesized green gold nanoparticles from Siberian ginseng induce growth-inhibitory effect on melanoma cells (B16). Artificial cells Nanomed Biotech. 2019;47(1):3297-305.

- Hasan A, Khan JA, Taqi M, et al. Predictors for Proximal Caries in Permanent First Molars: A Multiple Regression Analysis. J Contem Dental Pract. 2019;20(7):818-21.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at,Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref