Research Article - Journal of Finance and Marketing (2022) Volume 6, Issue 1

Gender bias in banking and the great financial crisis.

Jessica Dunn*

Assistant Professor of Finance, Murray State University, Murray, Kentucky, USA

- Corresponding Author:

- Jessica Dunn

Assistant Professor of Finance

Murray State University

Murray, Kentucky, USA

Email- jdunn13@murraystate.edu

Received: 19-Oct-2021, Manuscript No. AAJFM-21-44970; Editor assigned: 21-Oct-2021, PreQC No. AAJFM-21-44970(PQ); Reviewed: 5-Nov-2021, QC No. AAJFM-21-44970; Revised: 25-Dec-2021, Manuscript No. AAJFM-21-44970(R); Published: 1-Jan-2022, DOI:10.35841/aajfm- 6.1.101

Citation: Dunn J. Gender bias in banking and the great financial crisis. J Fin Mark. 2022; 6(1): 101.

Abstract

This study seeks to determine the relationship between women serving as CEO’s of Bank Holding Companies (BHC’s) between 2003-09, a period leading up to and into the great financial meltdown and a very dark time in banking history. We investigate the presence of a strong gender bias in banking regarding top leadership. We examine all publicly traded BHCs over the period using handcollected data. A close examination of the data finds that a very small fraction of CEO’s are female. We also examine CEO changes over this period to see if there is a trend towards equality in the gender gap. In addition, we compare the performance and riskiness of institutions with female CEOs with those of male CEOs by comparing variables such as bank size, capital position, loan composition, etc.

Keywords

Financial crisis, Banking history, Capital position.

Introduction

This study focuses on the trends of Bank Holding Companies (BHCs) for whom women serve as the CEO. We examine factors and qualities that make a quality CEO, trends towards equality, financial performance, and risk adversity of women versus men in this position. Specifically, we are taking a deeper look into 2004 through 2008, a period leading up to and into the great financial crisis [1].

Historically, gender has had a large impact in the workplace regarding perception of qualification. Over the last decade, there has been a shift in publicity around women taking on leadership roles across all levels of an organization. This can be seen in more groups empowering women leaders in workplaces and an upward trend in women CEOs across all industries. One fact quickly became evident as we delved deeper into the study; there is very little literature regarding female BHC CEOs. Fortunately, there are several studies concerning female CEOs in other industries, from which we extrapolate our findings.

Data

Information concerning CEO information was retrieved from the SEC’s Electronic Data Gathering and Retrieval System (EDGAR). Proxy statements were analyzed to determine CEO changes. In the event of a CEO change, additional SEC filings were analyzed to determine the exact date of the transition.

Our sample includes all publicly traded Bank Holding Companies (BHCs) over a period from 2003-2009. Although the data was plentiful, one area missing in all data sources analyzed was the gender of the BHC’s CEO. Thus, the authors assigned gender based on traditional male/female names, pronouns, and pictures. Although this method is not fool proof, we believe it provides the proper validity to move forward with the study. The data showed 17 female CEOs with 8 to 11 female CEOs in any given year. Overall, there were 72 firm-year observations with female CEOs.

Literature

This literature review is organized into three sections. In section one we describe some of the factors that affect a CEO’s ability to successfully lead a company. In sections two and three we introduce the effect that gender plays in the role of CEO’s and the resulting financial performance.

CEO management effectiveness factors

When you think of qualities of a successful CEO we tend to drift towards characteristics such as the ability to make decisions with speed and conviction, stakeholder engagement, proactive adaptation of effective management techniques, and delivering reliable results on a consistent basis. While these are historically strong qualities for a CEO to possess, one additional factor that is gaining more recognition is corporate social responsibility (CSR), a business model that helps a company be socially accountable to its stakeholders. The CEO is particularly relevant to CSR decisions. CSR is starting to play a more vital role in many firms [2]. According to, certain aspects of CSR are related to long-term compensation of CEOs [3]. This long-term direct relationship with compensation may discourage executives from making decisions that are overly risky, which in turn may actually benefit society. This is demonstrated in findings from a 2014 study where female CEOs are associated with higher levels of equity capital than male counterparts and are more averse to making risky decisions [4].

Another factor that plays a role in overall CEO performance is how well they work alongside others in the top management team (TMT). A study by concludes that CEO characteristics carry over into the TMT’s processes and firm performance [5]. The authors find that CEO and TMT diversity positively affect firm performance. Despite this, even after accounting for multiple types of business segments, the majority of the CEOs and TMT members are male. Argue that CEOs possessing relationship-oriented behaviors may achieve higher levels of firm performance.

Finally, we will look at risk as a whole in terms of CEO performance. A major study by Phuong (2015) focuses on risk and CEO compensation during the 2004 – 2008 period. They investigated CEO salaries, CEO bonuses, other CEO compensation, Percentage of CEO salaries, percentage of CEO bonuses and percentages of CEO’s other annual compensation. Based on a sample size of 63 large banks, the overall conclusion was that none of these factors had a statistically significant impact on the riskiness of the bank CEOs as originally expected. Similar studies have found that female CEOs are more risk averse than male [6].

Impact of gender on CEOs

A look at the C-level of most industries shows a noticeable lack of female CEOs. In this section we examine personal and/or professional events that have helped motivate, or remove a lack of motivation, to help females become CEOs. This, of course, is a subject with much depth and breadth, and we are just scratching the surface of these events [7]. The path to the C-suite may begin early in life. A 2003 study by shows that even from early childhood there is a different reward structure for males versus females. Risk taking, on average, gets rewarded for males and discouraged for females in childhood play [8]. Pallier finds that this reward system can promote less self-confidence and selfesteem at an early age for females versus males. Another factor that seems to play a role in the early development of female business leaders is the environment in which they were raised. A study by shows that a large percentage of female CEOs came from families where the father was self-employed in a small business. This environment would likely have a positive effect on a future CEO understands of the risk versus reward tradeoff and application to most business decisions. Examinations of gender within the C-Suite show that women are most likely to take on the role of Chief Management Officer and Chief Human Resources Officer [9].

The literature also shows that women are more likely to land at the helm of struggling company versus a financially stable one. The difficulty in turning around these struggling companies, in addition to the extra scrutiny on the female CEO, leads many not to accept these positions and gives companies a reason to not hire women in the future [10]. A great example of this is evident in a study by [11].Where they asked 122 students to rate a male and female for position of CEO in both a well performing company and one in financial crisis. Their results showed that people tend to choose a male for companies that are already doing well and a female when the company is in crisis. This should lead to more female CEO appointments of BHCs as banks tried to recover for the financial meltdown but is this the case?

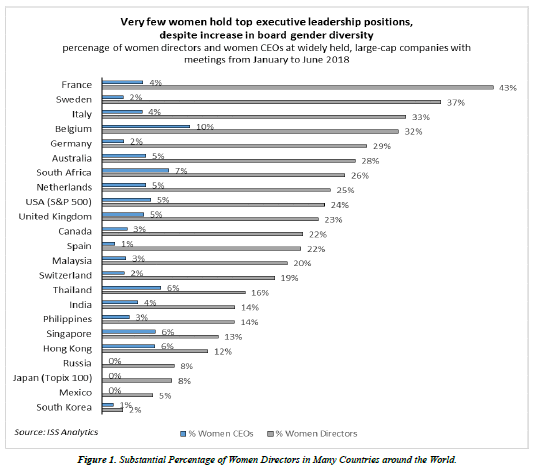

A study by shows the discrepancy in male versus female CEOs from 1992 to 2004 [6]. Furthermore, as clearly shown in Figure 1, in 2018 we see a substantial percentage of women directors in many countries around the world [12]. However, the overall percentage of women CEOs remains much lower. Even though female numbers are lower, a female CEO tends not to make much of a difference to stockholders according to a study by [13]. They find the announcement of a female CEO does not make a significant difference compared to the announcement of a male CEO in regards to stock price. Finally, when women do get the chance to lead a large corporation the results tend to be favorable. Of the 24 female CEOs leading S&P 500 companies, 13 of these women have led their companies’ stocks to outperform the index, on average, over the course of their tenure [14].

A summary of literature available shows that there is a large gap in the number of women versus men in CEO positions of BHCs. There are close to 100 bank holding companies in the United States with assets of more than $10 billion; however, in 2011 only five of these had a female CEO. In 2014 we seen this number drop down to only three [10]. We have seen a decline in the number of total BHCs in past years due to periods of economic crisis, consolidation spurred by the relaxation of state branching and national interstate banking restrictions, and voluntary mergers between unaffiliated banks [15]. By the end of 2018 there were 133 BHCs with more than $10 billion in total assets.

It is clearly shown that more research needs to be done on women and financial institutions. The issue lies in the data available, of which there is little. It would be easy for the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC) to break down data by CEO gender, yet this has not happened to date thus hampering meaningful studies in this area [16].

Results

We first look for difference in size between BHCs led by women versus those led by men in terms of total assets.

We see from Table 1 that the distribution for BHC sizes looks very similar across both genders until the median. Half of the BHCs led by both women and men have assets under about $1.65 billion. Beyond that there appears to be a significant difference. The next 25% of women led BHC’s have assets under $2.44 billion while for men the corresponding number is $5.07 billion. The difference is further exaggerated for the maximum size where BHC’s led by men reach up to 20 times the size of the biggest BHC led by a woman. This difference in distributions should translate into a significant difference in the means between the two groups. Upon calculating we find that this is indeed so. The average size of BHC’s led by women is $1.83 billion while the corresponding number for men is $27.9 billion, with the t-statistic for the difference between means at a highly significant value of -7.61. We interpret this result as indicating that in addition to the fewer number of women being hired to lead BHCs in general, there is a further compression effect at the top where women are even more unlikely to be leaders of large BHCs.

| Group | Minimum | 1st Quartile | Median | 3rd Quartile | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 231,900 | 710,000 | 1,637,000 | 2,437,000 | 11,950,000 |

| Male | 158,700 | 764,700 | 1,653,000 | 5,071,000 | 2,231,000,000 |

Table 1: Distribution of BHCs by Total Assets ($ ‘000).

In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, a lot of banks were found under-capitalized, leading to calls for increased regulation. We now turn to examine if there are any significant differences between women- and men-led BHCs in terms of capitalization (Table 2).

| Female | Male | T-statistic | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Domestic Deposits | 75.16% | 75.81% | -0.75 |

| Total Equity Capital | 9.36% | 9.11% | 0.74 |

Table 2: Capital Structure (% of Total Assets)

Here we see no significant difference between the two groups, indicating that BHCs led by women were just as well-prepared as those led by men prior to and during the financial crisis. We also looked for difference in the share of assets financed by domestic deposits since these would be less prone to withdrawal risk during global financial crises such as the one in 2008. Again, we found no significant difference here. One of the most adverse effects of the financial crisis was the liquidity crunch where banks were considerably more reluctant to lend because of the uncertainty surrounding the value of their assets and/or the ability of borrowers to repay during a recession. We thus now turn to a measure of lending.

| Female | Male | T-statistic | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Loans | 73.14% | 68.87% | 4.23 |

| Real Estate Loans | 74.66% | 75.85% | -0.94 |

| C&I Loans | 17.41% | 15.11% | 3.318 |

Table 3: Loans (% of Total Assets).

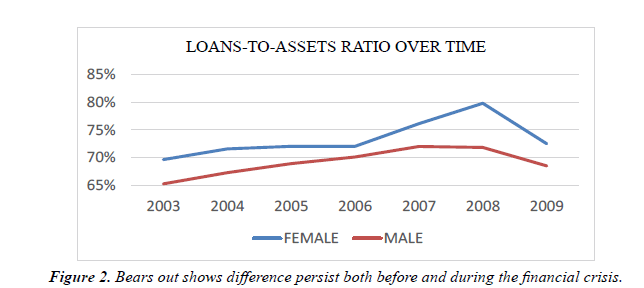

We see from Table 3 that there was in fact a significant difference in loans between the two groups. The difference is about 4.5 percentage points and is statistically very significant. Looking deeper on the potential impact of this difference on businesses, we see that BHCs led by women made on an average 2.4 percentage points more in commercial and industrial (C&I) loans compared to those led by men. This could have a significant impact during the financial crisis. Figure 2 bears out this observation further. We see this difference persist both before and during the financial crisis.

Finally, we look for any difference in performance and riskaversion between these two groups. We use two popular measures to examine risk in the banking industry – nonperforming loans ratio and risk-based capital ratio. We measure performance using return on equity (ROE).

We see in Table 4 that there is no significant difference in either risk or performance between the two groups. Therefore, both in terms of risk-aversion and profitability, BHCs led by women perform just as well as those led by men.

| Female | Male | T-statistic | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-performing Loans | 2.33 | 2.29 | 0.17 |

| Risk-based capital ratio | 0.6 | 0.67 | -0.40 |

| ROE | 13.48 | 14.18 | -1.06 |

Table 4: Risk & Performance Measures.

Summary

The first item of significance learned from this study is that more easily accessible data needs to be made available by bank regulatory agencies. This would allow for more robust analyses and further the cause for women to rise to the C-suite of commercial banks and bank holding companies. Our manually retrieved data shows very few women leading BHCs, and even fewer leading BHC’s with assets in excess of $10 billion. However, if one accounts for size, we find that BHC’s let by women and men are remarkably similar. The differences are sizeable in asset composition. Female led BHC’s tend to have a higher percentage of assets in the form of loans. Two specific areas are total loans and commercial and industrial loans. Male led BHCs made slightly more real estate loans over the examination period. BHCs with female CEOs also had a higher overall percentage of loans to assets for the entire period of 2004 to 2008. It is interesting that as male-led BHC’s started decreasing loans to assets in 2007 female-led BHC’s steadily increased their loan to assets into 2008, at which time the percentage started to drop. One might jump to the conclusion that because of increasing loans during a difficult economic period the percentage of non-performing loans for female led BHCs would have been higher than their counterparts. This, however, is not the case as both groups of non-performing loans were extremely close. This is also the case for return on assets for both groups; they were extremely similar over the study period.

Conclusion

What we can take away from this study is that women deserve their place in the C-suite just as much as men. We also show that the stereotype that female CEOs are more risk averse and thus less likely to take advantage of riskier but higher yielding loan opportunities is false. As the financial crisis was upon us female CEOs continued to make loans while male CEOs tended to back off and commit assets to safer investment opportunities. However, the number of non-performing loans remained approximately equal, showing that female CEO’s were making quality loans during this time.

It is apparent that much more study needs to be done in this area. With the regulators making the data available, it would be very interesting to determine if there is a difference between the performance of male and female led banks at the regional and community bank level.

References

- Wang H, Tsui AS, Xin KR. CEO leadership behaviors, organizational performance, and employees' attitudes. The Leadership Quarterly. 2011;22(1):92-105.

- Fabrizi M, Mallin C, Michelon G. The role of CEO’s personal incentives in driving corporate social responsibility. J Business Ethics. 2014;124(2):311-26.

- Wilf M.International politics of finance and bank regulations(Doctoral dissertation, Princeton University).

- Le TP.CEO Compensation and Risk-Taking in Banking Industry(Doctoral dissertation, Université de Lorraine).

- Buyl T, Boone C, Hendriks W, et.al. Top management team functional diversity and firm performance: The moderating role of CEO characteristics. J Management Studies. 2011;48(1):151-77.

- Kowalik M, Davig T, Morris CS, et.al. Bank consolidation and merger activity following the crisis. Economic Review. 2015;1612387(100):31-49.

- Fitzsimmons TW, Callan VJ, Paulsen N. Gender disparity in the C-suite: Do male and female CEOs differ in how they reached the top?. The Leadership Quarterly. 2014;25(2):245-66.

- Palvia A, Vähämaa E, Vähämaa S. Are female CEOs and chairwomen more conservative and risk averse? Evidence from the banking industry during the financial crisis. J Business Ethics. 2015;131(3):577-94.

- Ferry, Korn. Directors and Boards. 12 August 2016. Picture.2019.

- Mahoney LS, Thorne L. Corporate social responsibility and long-term compensation: Evidence from Canada. J Business Ethics. 2005;57(3):241-53.

- Bruckmüller S, Branscombe NR. How women end up on the “glass cliff.”. Harvard business review. 2011;89(1/2):26.

- Khan WA, Vieito JP. CEO gender and firm performance. J Economics and Business. 2013;67:55-66.

- Brinkhuis E, Scholtens B. Investor response to appointment of female CEOs and CFOs. The Leadership Quarterly. 2018;29(3):423-41.

- ISS Analytics. "Women Executive and Board Gender Diveristy." ISS Analytics, n.d. Picture.

- Landy, Heather. American Banker. 19 June 2014. Document.2019.

- Pallier G. Gender differences in the self-assessment of accuracy on cognitive tasks. Sex roles. 2003;48(5):265-76.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref