Research Article - Journal of Clinical Dentistry and Oral Health (2022) Volume 6, Issue 2

Etching technique used for composite restoration in class I cavities

Reddy AB, Deepak S*

Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics, Saveetha Dental College, Saveetha University, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India

- *Corresponding Author:

- Deepak S

Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics

Saveetha Dental College

Saveetha University

Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences

Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India

E-mail: deepaks.sdc@saveetha.com

Received: 04-Mar-2022, Manuscript No. AACDOH-22-60799; Editor assigned: 07-Mar-2022, PreQC No. AACDOH-22-60799(PQ); Reviewed: 21-Mar-2022, QC No. AACDOH-22-60799; Revised: 23-Mar-2022, Manuscript No. AACDOH-22-60799(R); Published: 30-Mar-2022, DOI:10.35841/aacdoh-6.2.110

Citation: Reddy AB, Deepak S, Etching technique used for composite restoration in class I cavities. J Clin Dentistry Oral Health. 2022;6(2):110

Abstract

Background: Acid etching is the use of an acidic substance to prepare the tooth's natural enamel for the application of an adhesive. The application of weak acid, usually 30% phosphoric acid roughens the surface before bonding a resin filling or veneer. Aim: The aim of this study was to determine the etching technique used for composite restoration in class I cavities. Materials and Methods: A total of 5391 patients who had undergone class I composite restoration in the mandibular 1st molars were taken from April 2020 to March 2021.The data was collected from the patient management system. The data was collected and the analysis was done using SPSS by IBM version 23. Results: Out of 5391 composite restorations, 95.03% of the restorations were done using self etching technique and 4.97% of them were done using total etching technique. Conclusion: Total etching technique was the most common etching technique used in class I composite restorations.

Keywords

Composite, Etching technique, Self etch, Total etch, Molars.

Introduction

When utilised under posterior resin-based composite restorations, self-etching adhesives are thought to reduce postoperative sensitivity. With the release of a seventh generation adhesive system in late 2002, the development of “Generational” bonding technologies that improve the attachment of aesthetic restorative materials to tooth structure (enamel and dentin) continues to advance [1]. Changes in manufacturer component components and dentin treatment processes have resulted in the introduction of "simpler" selfetching adhesive solutions that combine an etchant, primer, and adhesive in one or two containers and are marketed as "all-inone" adhesives [2]. Previously, multi-bottle, total-etch systems with distinct etching, priming, and adhesive components were considered to be time consuming and technique sensitive [3]. Total-etch adhesive systems use phosphoric acid etchants in varied concentrations (30% to 40%) to prepare the enamel and dentin surfaces before applying separate primer and adhesive monomer agents [4].

Etching enamel removes the smear layer, demineralizes the inorganic enamel surface, and creates microporosities for a patent and mechanical bond. Etching dentin also eliminates the smear layer, demineralizes the dentin substrate, and opens the tubules of the dentin. Phosphoric acid etchants can produce over-conditioning of the dentin surface (organic [collagen] and inorganic [hydroxyapatite] components) with absolute demineralization of the dentin substrate in total-etch systems [5]. Dentinal tubules are also denatured and channelled, enhancing dentinal fluid flow and perhaps increasing posttreatment sensitivity [6].

Self-etch systems do not require a separate acid etch component or subsequent rinse operations because they are made up of aqueous mixes of acidic functional monomers, which are usually phosphoric acid esters [7]. Self-etch techniques also allow for total infiltration and penetration of resin monomers into the collagen network of demineralized dentin, thereby improving marginal integrity and reducing or eliminating patient symptoms [8]. Self-etch adhesive methods did not differ from total-etch adhesive systems in restoration sensitivity and marginal discoloration, according to a recent in-vivo investigation [9]. Other advantages of self-etch systems include lower method sensitivity and the elimination of the need for moist bonding, which is required with totaletch systems [10].

For the clinical lifetime of adhesive restorations, the strength of the connections between resin and tooth substrates is critical. When employing etch-and-rinse adhesives, bonding to enamel is regarded to be stable and long-lasting. Bonding to enamel has recently been proven to seal and protect the more fragile resin–dentin bond from water deterioration [11]. Our team has extensive knowledge and research experience that has translated into high quality publications [12-30].

Materials and Methods

It is a single cantered retrospective study conducted at Saveetha dental college and hospitals, Chennai. A total of 5391 patients who had undergone class I composite restoration in the mandibular 1st molars, predominantly South Indians, were included in the study. Ethical clearance was obtained from the International review board. The study was conducted from April 2020 to February 2021. Validation to the study was done by undergraduate, postgraduates and all faculty members of Saveetha dental college.

Data collection was done by using patient management software which has all patients’ records. It is a recording system of all patients of all data related to the medical and dental history of patients and treatment done in Saveetha dental college. The collected data was tabulated under the following parameters - name, age, gender and etching technique. The main variables included are the presence of etching technique, age and gender.

The data analysis was performed using SPSS software (version 23). The chi square test and Pearson correlation was done. The chi square test was used to compare the data and checked for the distributions at 0.05 level of significance for effect of statistical significance.

Results and Discussion

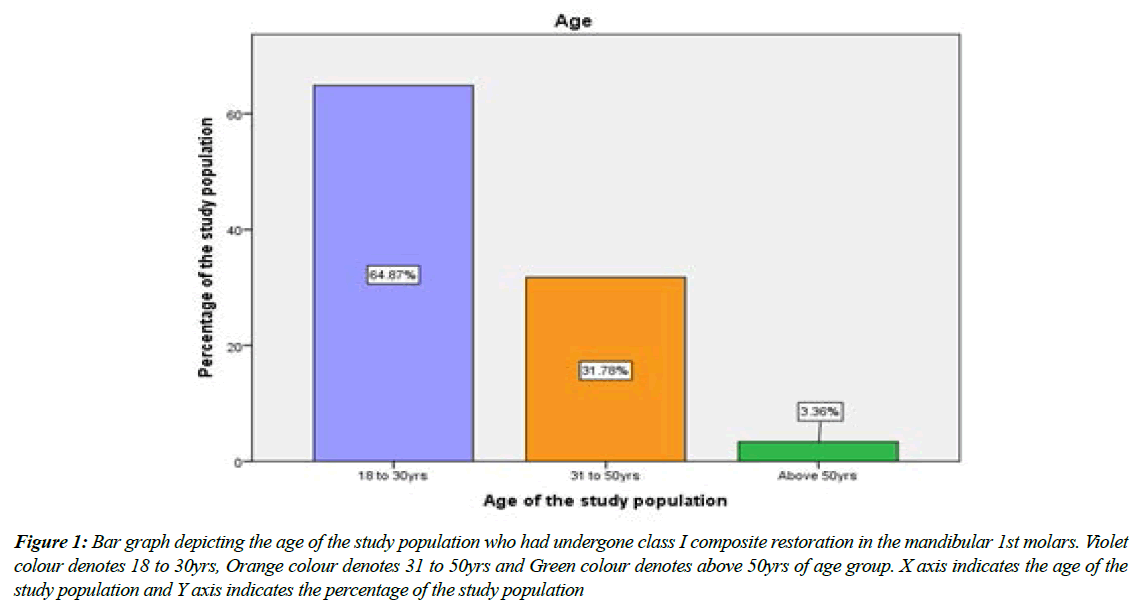

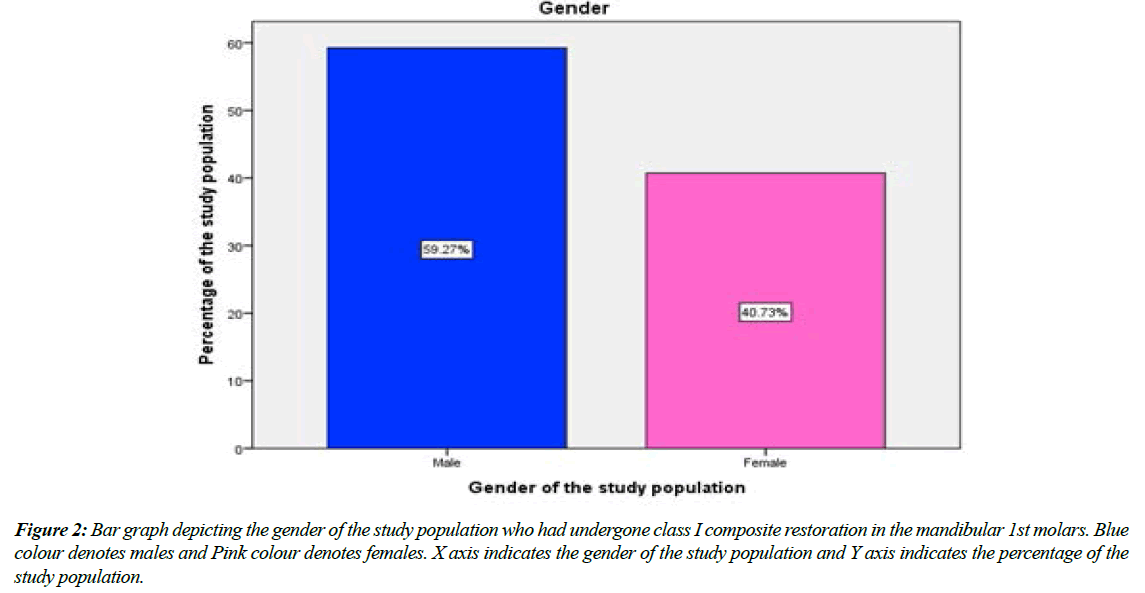

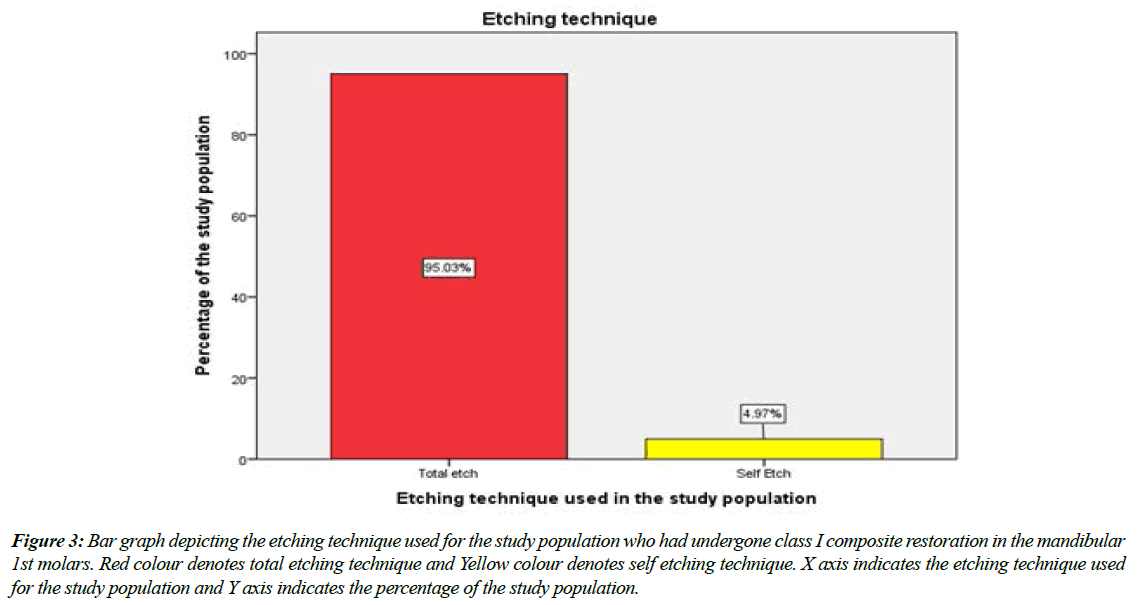

The data collected from the digital archives was tabulated, imported to SPSS and descriptive statistics was performed. Out of 5391 patients, the age of 64.87% of the population ranged from 18 to 30 years, 31.78% of them belonged to the age group of 31 to 50yrs and 3.36% of them were above 50yrs (Figure 1). 59.27% of them were males and 40.73% of the patients were females in the entire study population (Figure 2). The etching technique used for class I composite restoration in the mandibular 1st molars was categorised into 2 groups, namely self etch and total etch. Out of 5391 composite restorations, 95.03% of the restorations were done using self etch technique and 4.97% of them were done using total etch technique (Figure 3).

Figure 1: Bar graph depicting the age of the study population who had undergone class I composite restoration in the mandibular 1st molars. Violet colour denotes 18 to 30yrs, Orange colour denotes 31 to 50yrs and Green colour denotes above 50yrs of age group. X axis indicates the age of the study population and Y axis indicates the percentage of the study population

Figure 2: Bar graph depicting the gender of the study population who had undergone class I composite restoration in the mandibular 1st molars. Blue colour denotes males and Pink colour denotes females. X axis indicates the gender of the study population and Y axis indicates the percentage of the study population.

Figure 3: Bar graph depicting the etching technique used for the study population who had undergone class I composite restoration in the mandibular 1st molars. Red colour denotes total etching technique and Yellow colour denotes self etching technique. X axis indicates the etching technique used for the study population and Y axis indicates the percentage of the study population.

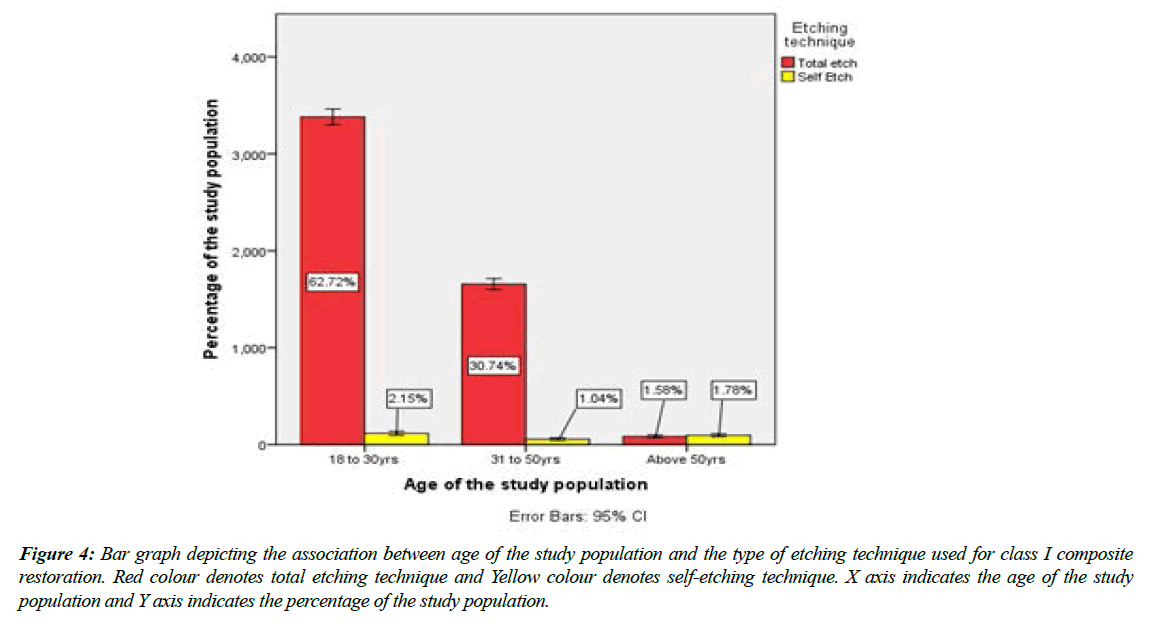

An association was done between age group of the study population and etching technique used for class I composite restorations. Out of 64.87% of the population who were aged from 18 to 30 yrs., 62.72% of the restorations were done using total etch technique and 2.15% of the restorations were done using self etching technique. Out of 31.78% of them who belonged to the age group of 31 to 50yrs, 30.74% of the restorations were done using total etching technique and 1.04% of them using self etching technique. Out of 3.36% of them were above 50yrs, 1.58% of the restorations were done using total etching technique and 1.78% using self etching technique (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Bar graph depicting the association between age of the study population and the type of etching technique used for class I composite restoration. Red colour denotes total etching technique and Yellow colour denotes self-etching technique. X axis indicates the age of the study population and Y axis indicates the percentage of the study population.

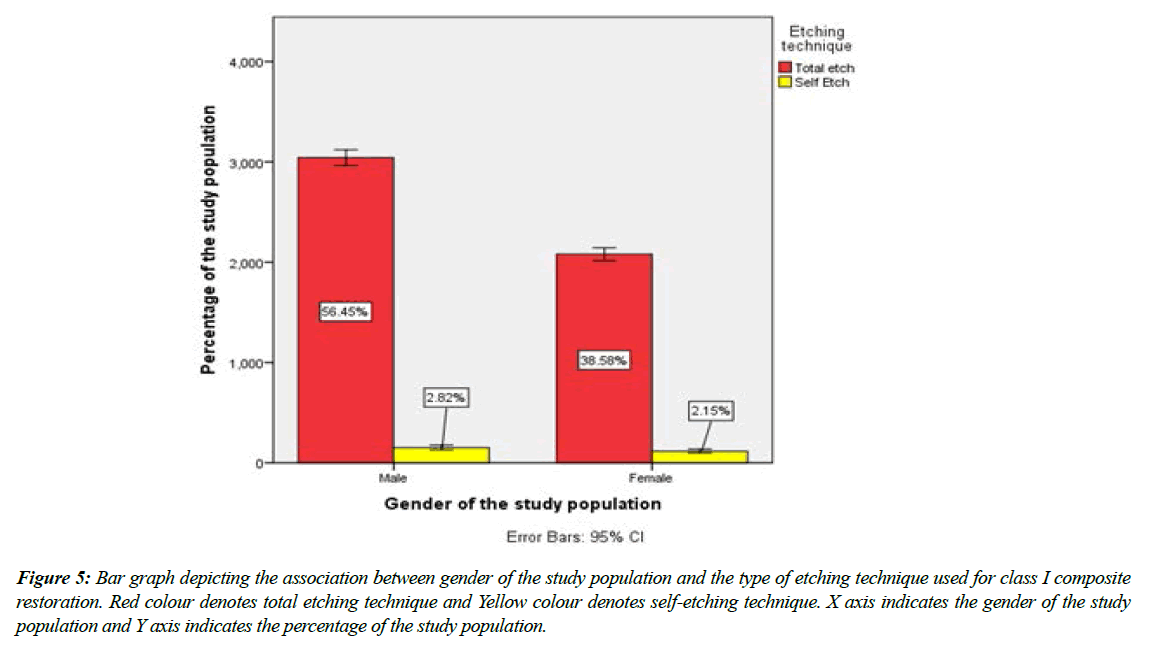

An association was done between gender and the etching technique used for class I composite restorations. Out of 59.27% of the male patients, 56.45% of them had undergone class I composite restorations using total etch technique and 2.82% with self etching technique. Out of 40.73% of the female patients, 38.58% of them had undergone class I composite restorations using total etching technique and 2.15% with self etching technique (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Bar graph depicting the association between gender of the study population and the type of etching technique used for class I composite restoration. Red colour denotes total etching technique and Yellow colour denotes self-etching technique. X axis indicates the gender of the study population and Y axis indicates the percentage of the study population.

A study given by Owens et al. [31], states that “A comparison of the self-etch adhesives at the enamel margin revealed Bond had significantly less leakage compared to the Nano-Bond group. No other significant differences were recorded between self-etch adhesives”.

A study given by Erickson et al. [32], states that “An inter-group comparison revealed significantly lower leakage at the enamel margin versus the dentin margin of all adhesive groups”. A study states that, there was concern that phosphoric acid placed on dentin would cause pulpal inflammation and necrosis. Early results reported with dentin etching were disappointing because the adhesive resin utilized was the same unfilled hydrophobic bonding resin (i.e. Bis-GMA) used for etched enamel. The hydrophobic resin would not wet the moist, vital dentin, and predictable adhesion could not be produced. Error Bars help to indicate estimated error or uncertainty to give a general sense of how precise a measurement is. This is done through the use of markers drawn over the original graph and its data points. Typically, Error bars are used to display either the standard deviation, standard error, confidence intervals or the minimum and maximum values in a ranged dataset.

A study given by Eliades et al. [33], states that they demonstrated the success of the etch-and-rinse total-etch adhesive bond based upon the addition of a hydrophilic monomer [eg: hydroxyethyl methyl methacrylate (HEMA)] to the primer and adhesive. This hydrophilic monomer allows the adhesive resin to penetrate the peritubular dentin and dentinal tubules. At the same time, Bowen was investigating the use of a dentin primer that actually was a self-cure adhesive that was painted on the enamel and dentin; it produced clinically acceptable bonds. This primer was commercialized to become two of the earliest etch-and-rinse total-bond adhesives introduced and that are still being used successfully.

The dispute over total etching vs. self etching continues, but we now have a third option in the form of selective etching or a hybrid etching process. Selective etching combines the advantages of both total etch and self-etching techniques.

Phosphoric acid is great for etching enamel, which is one of its many uses. Phosphoric acid is applied to the enamel surfaces, avoiding the dentin, in a selective or hybrid etching procedure. The gel is rinsed off the tooth after 15 seconds, and the tooth is dried. This approach maximises enamel bond strengths while removing the possibility of over-drying or over-etching the dentin after rinsing off phosphoric acid. A phosphoric acid gel that is viscous enough to stay on the enamel and not run is required for this approach to work.

Conclusion

The most common etching technique used in class I composite restoration was total etching technique. In this retrospective study, dietary and nutritional patterns of the patient, smoking, medical conditions (such as diabetes), were not recorded. Nevertheless, within the limitations of the present study, it can be said that there is a higher preference for total etching technique than self etching technique.

Acknowledgement

The authors sincerely acknowledge the Medical record department faculties in helping and sorting out data’s pertinent to this study.

Conflict of Interest

None to declare

Source of Funding

The present project is funded by

Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences, Saveetha Dental College and Hospitals, Saveetha University, India

Rakshith private limited.

References

- He Z, Shimada Y, Tagami J. The effects of cavity size and incremental technique on micro-tensile bond strength of resin composite in Class I cavities. Dental Mat. 2007;23(5):533-8.

- Knibbs PJ. The clinical performance of a glass polyalkenoate (glass ionomer) cement used in a'sandwich'technique with a composite resin to restore Class II cavities. Br Dental J. 1992;172(3):103-7.

- Ruiz JL. Practical and Predictable Class II and III Direct Composite Restorations. Supra-Gingival Minimally Invasive Dentistry. 2017;183-203.

- Dietschi D, Herzfeld D. In vitro evaluation of marginal and internal adaptation of class II resin composite restorations after thermal and occlusal stressing. Euro J Oral Sci. 1998;106(6):1033-42.

- Ozel E, Tuna EB, Firatli S, et al. Effect of different parameters of Er: YAG laser irradiations on class V composite restorations: A scanning electron microscopy study. Scanning. 2016;38(5):434-41.

- Bauer JG. Contour of class V composite restorations. J Prost Dent. 1987;58(1):8-12.

- Martinez NC. Effect of the lingual margin configuration on the fracture strength of class IV resin based composite restorations under static loading. University of Iowa. 2015.

- Santos MJ. A restorative approach for class ii resin composite restorations: a two-year follow-up. Operative Dent. 2015;40(1):19-24.

- Jackson RD. Class II composite resin restorations: faster, easier, predictable. Br Dental J. 2016;221(10):623-31.

- Muthukrishnan L. Imminent antimicrobial bioink deploying cellulose, alginate, EPS and synthetic polymers for 3D bioprinting of tissue constructs. Carbo Poly. 2021;260:117774.

- PradeepKumar AR, Shemesh H, Nivedhitha MS, et al. Diagnosis of vertical root fractures by cone-beam computed tomography in root-filled teeth with confirmation by direct visualization: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Endo. 2021;47(8):1198-214.

- Chakraborty T, Jamal RF, Battineni G, et al. A review of prolonged post-COVID-19 symptoms and their implications on dental management. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(10):5131.

- Muthukrishnan L. Nanotechnology for cleaner leather production: a review. Environ Chem Lett. 2021;19(3):2527-49.

- Teja KV, Ramesh S. Is a filled lateral canal–A sign of superiority?. J Dent Sci. 2020;15(4):562.

- Narendran K, MS N, Sarvanan A. Synthesis, Characterization, Free Radical Scavenging and Cytotoxic Activities of Phenylvilangin, a Substituted Dimer of Embelin. Ind J Pharmac Sci. 2020;82(5):909-12.

- Reddy P, Krithikadatta J, Srinivasan V, et al. Dental caries profile and associated risk factors among adolescent school children in an urban South-Indian city. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2020;18(1):379-86.

- Sawant K, Pawar AM, Banga KS, et al. Dentinal Microcracks after Root Canal Instrumentation Using Instruments Manufactured with Different NiTi Alloys and the SAF System: A Systematic Review. App Sci. 2021;11(11):4984.

- Bhavikatti SK, Karobari MI, Zainuddin SL, et al. Investigating the Antioxidant and Cytocompatibility of Mimusops elengi Linn Extract over Human Gingival Fibroblast Cells. Int J Enviro Res Public Hea. 2021;18(13):7162.

- Karobari MI, Basheer SN, Sayed FR, et al. An In Vitro Stereomicroscopic Evaluation of Bioactivity between Neo MTA Plus, Pro Root MTA, BIODENTINE & Glass Ionomer Cement Using Dye Penetration Method. Mat. 2021;14(12):3159.

- Rohit Singh T, Ezhilarasan D. Ethanolic extract of Lagerstroemia Speciosa (L.) Pers., induces apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in HepG2 cells. Nutr Cancer. 2020;72(1):146-56.

- Ezhilarasan D. MicroRNA interplay between hepatic stellate cell quiescence and activation. Euro J Pharmacol. 2020;885:173507.

- Romera A, Peredpaya S, Shparyk Y, et al. Bevacizumab biosimilar BEVZ92 versus reference bevacizumab in combination with FOLFOX or FOLFIRI as first-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer: a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;3(12):845-55.

- Raj R K. ß-Sitosterol-assisted silver nanoparticles activates Nrf2 and triggers mitochondrial apoptosis via oxidative stress in human hepatocellular cancer cell line. J Biomed Mat Res Part A. 2020;108(9):1899-908.

- Vijayashree Priyadharsini J. In silico validation of the non-antibiotic drugs acetaminophen and ibuprofen as antibacterial agents against red complex pathogens. J Periodontol. 2019;90(12):1441-8.

- Priyadharsini JV, Girija AS, Paramasivam A. In silico analysis of virulence genes in an emerging dental pathogen A. baumannii and related species. Archiv Oral Biol. 2018;94:93-8.

- Uma Maheswari TN, Nivedhitha MS, Ramani P. Expression profile of salivary micro RNA-21 and 31 in oral potentially malignant disorders. Braz Oral Res. 2020;34.

- Gudipaneni RK, Alam MK, Patil SR, et al. Measurement of the maximum occlusal bite force and its relation to the caries spectrum of first permanent molars in early permanent dentition. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2020;44(6):423-8.

- Chaturvedula BB, Muthukrishnan A, Bhuvaraghan A, et al. Dens invaginatus: A review and orthodontic implications. Br Dent J. 2021;230(6):345-50.

- Kanniah P, Radhamani J, Chelliah P, et al. Green synthesis of multifaceted silver nanoparticles using the flower extract of Aerva lanata and evaluation of its biological and environmental applications. Chem Select. 2020;5(7):2322-31.

- Owens BM, Johnson WW, Harris EF. Marginal permeability of self-etch and total-etch adhesive systems. Oper Denti. 2006 ;31(1):60-7.

- Erickson RL, De Gee AJ, Feilzer AJ. Fatigue testing of enamel bonds with self-etch and total-etch adhesive systems. Dental Mat. 2006;22(11):981-7.

- Rudawska A. Adhesives: Applications and Properties. BoD. 2016;398.

- Eliades G, Watts DC, Eliades T. Dental Hard Tissues and Bonding: Interfacial Phenomena and Related Properties. Springer Sci Bus Media. 2005;198.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at,Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref