Short Communication - Journal of Anesthetics and Anesthesiology (2017) Journal of Anesthetics and Anesthesiology

Reducing failure rate in rapid sequence intubation in emergency department

- *Corresponding Author:

- Surjya Prasad Upadhyay

Specialist Anaesthesiology NMC hospital DIP, Dubai UAE

Tel: 00971554078445

E-mail: run77in@yahoo.com

- *Corresponding Author:

- Piyush N Mallick, MD

Consultant Anaesthesiology Al-Zahra Hospital, Sharjah UAE

Tel: 00971554078445

E-mail: piyush_mallick@hotmail.com

Accepted date: March 22, 2017

Citation: Upadhyay SP, Mallick PN. Reducing failure rate in rapid sequence intubation in emergency department. J Anest Anesthes. 2017;1(1):6-9.

Abstract

Establishment of a patent and secured airway is a fundamental and central component of any resuscitation of an unstable patient. Without oxygenation and adequate ventilation, all effort or life-saving manoeuvre will fail. Endotracheal intubation is a live saving intervention in emergency with little room for error and must be performed in a limited time frame. Longer or repeated intubation attempts are associated with adverse clinical outcomes

Introduction

Establishment of a patent and secured airway is a fundamental and central component of any resuscitation of an unstable patient. Without oxygenation and adequate ventilation, all effort or life-saving manoeuvre will fail. Endotracheal intubation is a live saving intervention in emergency with little room for error and must be performed in a limited time frame. Longer or repeated intubation attempts are associated with adverse clinical outcomes. Airway management using technique of rapid sequence intubation (RSI) is an established technique of securing and protecting airway in emergency department (ED) for patients who are at risk of aspiration of food/blood into the lungs [1-3].

By definition, it involves administration of rapidly acting sedative and neuromuscular blocker simultaneously or in quick succession to anaesthetized a patient rapidly to facilitate rapid placement of endotracheal tube while minimizing the risk of pulmonary aspiration. The aim of RSI is to protect the airway with a cuff endotracheal tube as quickly as possible after anaesthetic induction, while reducing the risk of active or passive regurgitation. This is done without having to use bag mask ventilation after induction of anaesthesia, unlike an elective intubation. Avoidance of bag-mask ventilation minimizes the inflation of air into the stomach, which might otherwise provoke regurgitation [4-8].

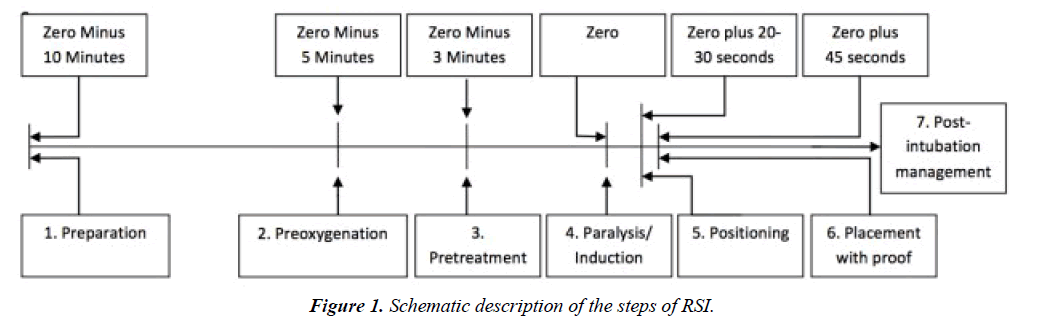

RSI key success lies on planning and execution and detailed consideration at multiple steps. Steps of RIS can be remembered as mnemonic 7 Ps that outline these key steps. Some author add 8th P as Cricoid Pressure after Pretreatment, but this procedure is controversial and has many drawbacks [8-10] (Figure 1).

Preparation and planning

Goal is to maximize the chance of intubation on first attempt. Failed first intubation invites adverse outcome. It should be quick, taking not more than 10 minutes. This step include assessing patient’s airway, formulate airway management plan including rescue plan, assembling necessary equipment and medications. Failure to identify difficult intubation or ventilation is one of the main cause of failed airway management [11,12]. A difficult airway may be either because of difficult bag-mask ventilation, difficult laryngoscopy and intubation, cricothyrotomy and difficult supraglottic airway insertion. It is not feasible in ED to do extensive airway evaluation in a sinking patient. While assessing airway, the basic approach should not be ignored, which include assuring airway patency, protection from aspiration and providing adequate oxygenation and ventilation. It is essential to recognized which patient need awake intubation/surgical airway. Patient with known or anticipated difficult airway, complete airway obstruction may not be a candidate for RSI. If difficult airway is anticipatedalways call anaesthetic in charge before attempting RSI [13,14].

Even in normal looking airway, there must be a backup plan for unanticipated difficult airway management. The backup plan depends on the clinical scenario, expertise of the clinician and availability of resources. Failure to formulate a backup plan is the main reason for airway catastrophes [15]. After quick assessment of airway, before proceeding to RSI, intravenous assess, basic cardiorespiratory monitors (pulse oximetry, ECG, non-invasive blood pressure) should be in place. Before proceeding to RSI basic things that should be at hand can be remembered using mnemonic SOAP-ME:

S=Suction; wide bore suction catheter/younker, functioning suction machine

O=Oxygen; high flow oxygen source, 2nd oxygen source,

A=Airway equipment, different types of laryngoscopes, endotracheal tube, stylets, bougies, videoscope etc.

P=Pharmacologic Agent; Induction agent, paralyzing agent and post intubation sedation/analgesic drug drawn and labelled.

ME=Monitoring equipment; basic standard monitoring, pulse oxymetry, non-invasive blood pressure, Capnography; ECG

Preoxygenation

Preoxygenation is most important in component of RSI specially in a compromised patient in ED. Adequate preoxygenation is to be done to denitrogenate the lungs and replaced air with oxygen in the lungs so that patient can tolerate longer period of apnea during the process of RSI. Standard preoxygenation in operative room is done via tight fitting mask attached to anaesthetic circuit and adequacy of which can be monitored by end tidal oxygen (FeO2) concentration which should be above 90% as a measure of adequate denitrogenation. The same cannot be applied in ED, patients who require RSI are in critically ill and likely desaturate rapidly despite achievement of High FeO2 during induction/ intubation, this occur due to number of factors such as underlying lung pathology, reduced functional residual volume, high metabolic requirements etc. Preoxygenation can be done with high flow oxygen using non-rebreathing mask, alternatively bagvalve- mask (BVM) with one way expiratory valve can be used with high flow oxygen for the same. Preoxygenation with BVM is comparable to that of anaesthesia circuit and superior to nonrebreathing simple mask with high flow oxygen [16]. Ideally all patients in ED who require intubation should continue to receive high flow oxygen. Three minutes preoxygenation is sufficient in patients with normal respiratory drive [17]. Alternately Eight full vital capacity (maximal expiration followed by maximum inhalation) breath can be used for preoxygenation which reduces the preoxygenation time to 60 seconds [18]. Unfortunately, many ED patients are already respiratory crippled and cannot take full vital capacity breath, the optimal duration of preoxygenation in ED has not been evaluated clinically. Alternatively, there are number of other techniques that has been described to prevent rapid desaturation during RSI. One such technique involves administration of high flow oxygen via nasal cannula which provides passive flow of oxygen when the patient is rendered apneic.

Apneic oxygenation

High flow nasal oxygen provides apneic oxygenation and prolonged the desaturation time permitting longer intubation attempt provided there should not be significant leakage mask seal due to nasal tubing, thereby, increases the success of intubation at first attempt. Apneic oxygenation has the potential to increase the safety of RSI in ED by reducing the number of intubation attempts and the incidence of hypoxemia [19]. Other techniques that can be utilized in selected patients are:

Head up position: Preoxygenation in 20° to 30° head up has shown to be more effective in prolonging the safe apnea period, particularly in obese patients, patients with abdominal distension. Care should be taken in patients with suspected spinal injury where spinal immobilization measure has not been applied [20,21].

Airway adjunct: Use of oral/nasopharyngeal airway can be a valuable adjunct in addition to head tilt, chin lift and jaw thrush, particularly in patients with obstructive airway. Head tilt and chin lift should be avoided in patients with suspected cervical spine injury.

Use of CPAP/PEEP: Varieties of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) or Positive end expiratory pressure (PEEP) device are available (some disposable) that can be utilized for patients who are unable to achieve adequate oxygen saturation despite high flow oxygen [22,23].

Manual assist ventilation: Manual assisted ventilation prior to intubation may be needed in patients not able to attained oxygen saturation above 90% despite the application of head up, high flow oxygen, airway adjunct or CPAP/PEEP. Routine application of manual ventilation before intubation in RSI is contraindicated, it should be reserved for refractory hypoxic patients only and when it is provided, it should be very gentle and slow ventilation.

Action plan for failed RSI

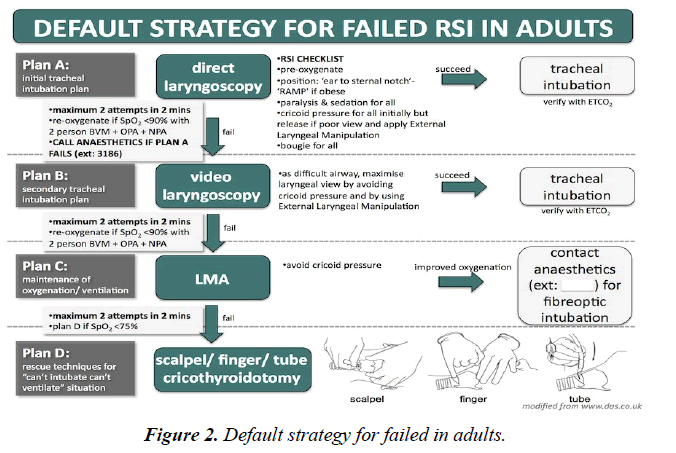

Prepared for failure to intubate and failure to ventilate scenario Clear Back up plan in the form of A, B, C, D should be discussed with each team member and everyone should be familiar with the plans and all the require equipment for the A, B, C, D should be readily at bed side. Plan A is conventional laryngoscopy and intubation, if plan A failed, there should be 2nd alternative, be it video laryngoscope, fiberoptic. Plan C is when both plan A and B failed, and when nothing working it is plan D emergency life-saving rescue measure to provide oxygenation. Below is a modified version of Difficult Airway Society (DAS -2015) [24] guideline that can be followed as a stepwise approach for failed RSI (Figure 2).

Video laryngoscopy

There is growing evidence of increasing success rate with different video laryngoscopy and has been validated by number of studies [25-28]. Video laryngoscopy offers the advantage of exact alignment of the pharyngeal and laryngeal optical axes in order to visualized the glottis and thereby may reduce the number of failed intubation attempt in novice operators but not for experienced operators [29], recent randomized trials has failed to show consistently higher fast pass success with less intubation time [30-32]. Although it provides superior glottic view but the superior view has not been translated clearly into higher success in intubation specially in RSI, where time and number of attempts are crucial factors in RSI for worse outcome. Main limitation of video laryngoscope in RSI may be the time to intubation. Despite the advent in video laryngoscope, it is mostly the direct laryngoscope, which continues to be the most commonly used device for RSI. Video laryngoscope may have a great role in difficult airway scenario (limited mouth opening, micrognathia, large tongue, cervical spine immobility) and may not offer many advantages in normal airway. It has not been placed as first line device in any algorithm for unanticipated difficult airway management.

Confirmation of successful intubation

All endotracheal intubation be it in ED, operative room or critical care area must be confirmed with quantitative wave-form capnography which should be the standard of care for every institution. Inadvertent esophageal intubation is not a sin, but failure to timely recognize and correction is an inexcusable offence.

References

- Sakles JC, Chiu S, Mosier J, et al. The importance of first pass success when performing orotracheal intubation in the emergency department. AcadEmerg Med. 2013;20(1):71-8.

- Goto T, Gibo K, Hagiwara Y, et al. Multiple failed intubation attempts are associated with decreased success rates on the first rescue intubation in the emergency department: A retrospective analysis of multicentre observational data. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2015;23:5.

- Sagarin MJ, Barton ED, Chng YM, et al. Airway management by US and Canadian emergency medicine residents: A multicenter analysis of more than 6,000 endotracheal intubation attempts. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;46(4):328-36.

- Brown CA, Bair AE, Pallin DJ, et al. NEAR III Investigators.Techniques, success, and adverse events of emergency department adult intubations.Ann Emerg Med. 2015;65(4):363-70.

- Li J, Murphy-Lavoie H, Bugas C, et al. Complications of emergency intubation with and without paralysis.Am J Emerg Med. 1999;17(2):141.

- Walls RM. Rapid-sequence intubation in head trauma.Ann Emerg Med. 1993;22(6):1008.

- Sinclair RCF, Luxton MC. Rapid sequence induction. Contin Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain.2005;5(2): 45-8.

- Walls RM. Rapid sequence intubation comes of age. Ann Emerg Med.1996;28:79-81.

- Policy Statement of the American College of Emergency Physicians.Rapid-sequence intubation.Reaffirmed by the ACEP Board of Directors October 2000; October 2006; and April 2012.

- Geradi MJ, Sacchetti AD, Cantor RM, et al. Rapid sequence intubation of the pediatric patient. Ann Emerg Med. 1996;28:55-74.

- American Society of Anaesthesiologists Task force on management of the difficult airway-Practice guidelines for management of the difficult airway: An updated report by the American Society of anesthesiologists task force on management of the difficult airway.Anaesthesiology. 2003;98(5):1269.

- Apfelbaum JL, Hagberg CA, Caplan RA, et al. Practice guidelines for management of the difficult airway: An updated report by the American Society of Anaesthesiologists Task Force on Management of the Difficult Airway.Anaesthesiology. 2013;118(2):251.

- Reed MJ, Dunn MJ, McKeown DW. Can an airway assessment score predict difficulty at intubation in the emergency department?Emerg Med J. 2005;22(2):99-102.

- Murphy M, Walls RM. Identification of the difficult and failed airway. In: manual of emergency airway management. Walls RM, Murphy MF, Luten RC, editors. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia 2004. p.70.

- Cook TM, MacDougall-Davis SR. Complications and failure of airway management. Br J Anaesth. 2012;109(1):68-85.

- Groombridge C, Chin CW, Hanrahan B, et al. Assessment of common preoxygenation strategies outside of the operating room environment. Acad Emerg Med. 2016;23(3):342-6.

- Weingart SD, Levitan RM. Preoxygenation and prevention of desaturation during emergency airway management. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;1-11

- Baraka AS, Taha SK, El-Khatib MF, et al. Oxygenation using tidal volume breathing after maximum exhalation. Anesth Analg.2003;97:1533-35.

- Sakles JC, Mosier JM, Patanwala AE, et al. First pass success without hypoxemia is increased with the use of apneic oxygenation during rapid sequence intubation in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2016;23(6):703-10.

- Ramkumar V, Umesh G, Philip FA. Preoxygenation with 20ºhead-up tilt provides longer duration of non-hypoxic apnea than conventional preoxygenation in non-obese healthy adults. J Anesth. 2011;25(2):189-94.

- Boyce JR, Ness T, Castroman P, et al. A preliminary study of the optimal anesthesia positioning for the morbidly obese patient. Obes Surg. 2003;13(1):4.

- Delay JM, Sebbane M, Jung B, et al. The effectiveness of non-invasive positive pressure ventilation to enhance preoxygenation in morbidly obese patients: A randomized controlled study. Anesth Analg. 2008;107(5):1707.

- Baillard C, Fosse JP, Sebbane M, et al. Non-invasive ventilation improves preoxygenation before intubation of hypoxic patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174(2):171.

- Frerk C, Mitchell VS, Mcnarry AF, et al. Difficult airway society intubation guideline group. Difficult Airway Society 2015 guidelines for management of unanticipated difficult intubation in adults. Br J Anaesth. 2015;115(6):827-848

- De Jong A, Molinari N, Conseil M, et al. Video laryngoscopy versus direct laryngoscopy for orotracheal intubation in the intensive care unit: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40(5):629-39.

- Lewis SR, Butler AR, Parker J, et al. Videolaryngoscopy versus direct laryngoscopy for adult patients requiring tracheal intubation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.2016;15:11.

- Sakles JC, Javedani PP, Chase E, et al.The use of a video laryngoscope by emergency medicine residents is associated with a reduction in esophageal intubations in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22(6):700-7.

- Sakles JC, Mosier JM, patanwala AE, et al. The C-MAC® video laryngoscope is superior to the direct laryngoscope for the rescue of failed first-attempt intubations in the emergency department. J Emerg Med.2015;48(3):280-6.

- Mort TC. Emergency tracheal intubation: Complications associated with repeated laryngoscopic attempts. Anesth Analg. 2004;99(2):607-13.

- Sulser S, Ubmann D, Schlaepfer M, et al. C-MAC videolaryngoscope compared with direct laryngoscopy for rapid sequence intubation in an emergency department: A randomised clinical trial. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2016;33(12):943-948.

- Driver BE, Prekker ME, Moore JC, et al. Direct versus video laryngoscopy using the C-MAC for tracheal intubation in the emergency department, a randomized controlled trial. Acad Emerg Med. 2016;23(4):433-9.

- Desai B, Rogers J, Eason-Bates H. Has video laryngoscopy improved first pass and overall intubation success in the university of Florida health emergency department? J Eme Med Int Care. 2016;2(1):108.