Research Article - Addiction & Criminology (2023) Volume 6, Issue 5

The culture of recovery: an antidote to coloniality.

Patton D*, Best D, Pula P & Hollandy YDepartment of Criminology and Social Science, College of Business, Law & Social Sciences, UK

- *Corresponding Author:

- Patton D

Department of Criminology and Social Science

College of Business, Law & Social Sciences, UK

E-mail: d.patton@derby.ac.uk

Received: 19-Sep-2023, Manuscript No. AARA-23-114135; Editor assigned: 21-Sep-2023, PreQC No. AARA-23-114135 (PQ); Reviewed: 04-Oct-2023, QC No. AARA-23-114135; Revised: 10-Oct-2023, Manuscript No. AARA-114135 (R); Published: 18-Oct-2023, DOI: 10.35841/aara-6.5.166

Citation: Patton D, Best D, Pula P, et al., The culture of recovery: An antidote to coloniality. Addict Criminol. 2023;6(5):166

Keywords

Addiction recovery, The culture of recovery, Coloniality, Antidotes, Recovery capital, CHIME

The Culture of Recovery: An Antidote to Coloniality

Debate surrounds the role and contribution of lived experience to the drug addiction recovery knowledge base. Bruce Alexander's book, 'The Globalisation of Addiction,' shows how coloniality via globalization, capitalism, and consumer culture have colonised and marginalized communities, their cultures, knowledge, beliefs, ceremonies, values, rituals, and practices [1]. This includes those in addiction and recovery pathways. This article posits that recovery pathways collectively create a culture of recovery. The two key questions this article explores is: 1. what are some of the main features of the culture of recovery? 2. What potential impact do personal recovery journeys intersecting with cultural capital have in creating social and structural change? This addresses a key gap in the literature that tends to focus on factors and forces at the individual level. The focus here is to extend the typical gaze of recovery studies to begin to explore features at the cultural level operating during recovery whilst considering their implications for social and structural change.

This paper will begin by discussing the impact of coloniality on addiction and recovery. Coloniality is deemed to be the dominant influence shaping the structures and culture within society. The discussion will present a range of perspectives on the impact of coloniality. The paper will then move on to consider frameworks which have been shown to reduce the negative effects of drug addiction pathways and promote recovery before presenting the methods used to explore the main features of the culture of recovery. Such frameworks are key as they suggest that the negative impact of coloniality can be overcome.

The Impact of Coloniality’s Matrix of Power on Addiction and Addiction Recovery

Colonialism and coloniality are terms which are often used erroneously. Whilst colonialism in simple terms refers to the historical, physical and political occupation and oppression and rule of geographic territories and people by another. Whereas, [2] defines coloniality as “the underlying logic of the foundation and unfolding of Western civilization” and its modernity which still endures today [3]. It is predicated on a matrix of power which has four interconnected domains: the control of knowledge and understanding (epistemology, science, ontology, religion etc); the control of authority (the nation state and its institutions); the control of economy (capitalism, exploitation of labour, land appropriation); the control of subjectivities (being, sensing and thinking) [3-5].

The following section will discuss perspectives from several researchers who highlight a range of colonial factors and forces such as global, structural, neo-liberal, capitalist forces as leading to addiction, isolation, social erosion and diminishing health and well-being. The impact of coloniality in relation to addiction and addiction recovery can be seen in the matrix of power discussed below.

Coloniality and it’s- Control Over the Economy

Alexander highlighted the potent role of coloniality and its control over the economy. He demonstrated how globalisation via a capitalist free market economy creates global dislocation which he found to be a precursor to addiction. He highlighted how the cultural traditions from a range of communities impinge upon the free market economy [1]. Therefore, social structures, paradigms and hierarchies were established within society to suppress and homogenise these cultural traditions to establish a free market society. Alexander provides multiple examples of the widespread impact that the control of the economy has on various life domains impacting everyday life.

“In order for “free markets” to be “free,” the exchange of labour, land, currency, and consumer goods must not be encumbered by elements of psychosocial integration such as clan loyalties, village responsibilities, guild or union rights, charity, family obligations, social roles, or religious values. Cultural traditions “distort” the free play of the laws of supply and demand, and thus must be suppressed. In free market economies, for example, people are expected to move to where jobs can be found, and to adjust their work lives and cultural tastes to the demands of a global market.” [1].

He argues that as free market globalization speeds up and spreads so does addiction, in this sense he regards addiction as being globalised as a result of the structural norms, values and practices that permeate the culture of the free market capitalist society.

Gabor Maté’s work also highlights the negative effects of a hypercapitalist ideology within society promoting individualism, competition and self-centredness [6]. Highlights the role of macro structural forces and systems viewing society as toxic due to the assumptions that it makes about what’s necessary for human life [7]. He argues that these structures are producing increasing levels of addiction, mental health, suicide, depression, and self-harm etc. Similarly, also provides evidence as to how the structures of post-industrial societies have created social erosion and severely undermined participation for some groups in civic, environmental, and economic life. He cites the impact of this as a social and health hazard to people within communities which has created disconnection, isolation and loneliness [8].

Putnam has documented the declining connection amongst family, friends, neighbours, and social structures but highlights the vital role social capital plays to civic and personal health [9]. In 2018, the UK appointed a minister of loneliness due to more than nine million people often or always feeling lonely and due to the detrimental impact of loneliness on health and well-being [10]. The Jo Cox Loneliness Commission Report [10] highlighted a range of potent structural features of UK society in creating high levels of loneliness in society including social and cultural norms, the impact of modern lives on work/life balance, communities becoming more ‘closed off’, the rise of digital and online engagement and perceived stigma of loneliness etc [11]. Research by Harvard Business Review has shown that loneliness and weak social connections are associated with a reduction in lifespan similar to that caused by smoking 15 cigarettes a day and greater than that associated with obesity [12]. Understanding the impact of social erosion, isolation and social connectedness has led [13] to state that health and wellbeing “are holistic social, political, economic and ecological processes.” Research also highlights how social capital has diminished with capitalism and patriarchy as colonial structures of domination, eroding and destroying the role and place of larger units of extended kin within society [14]. Family and community have been replaced with a small privatised autocratic unit which has increased alienation and facilitated inequalities and abuses of power against communities with specific characteristics. Block P posits a free-market ideology embedded within western society’s consumer culture with its constellations of empire and control as being responsible for a culture of addictive consumption with accompanying beliefs in competition, scarcity, and acquisition resulting in isolation, polarization, reductions in health and well-being and increased violence [15]. Due to declining social capital and connections, community connectors have been highlighted as having a central role in helping to build social and community capital [16].

Coloniality’s Control Over Knowledge

Coloniality’s control over knowledge, has created an ideological perspective of domination with the advent of positivism which has shaped the addiction, treatment and harm reduction fields. This perspective is embedded in practice via a medical model approach to addiction and recovery. Practice is therefore clinic focussed, led by professional experts, focussed on individuals, their deficits and the risks they pose, with an emphasis on replication of an evidence-based service. This has esteemed certain voices, methods and approaches including forms of knowledge whilst de-legitimising and marginalising others. The dominance of coloniality’s control of knowledge has hindered both the knowledge and practice bases within the field. The impact of coloniality’s control over knowledge, especially as expressed through the prevention and treatment agendas literature, have overly decontextualised and depoliticised crime and addiction pathways from its social-structural roots, producing analyses that are too individualistic, agentic, and that over- responsibilise individuals, providing reductionist accounts and which thereby reproduce a colonial epistemology [17,18].

Coloniality’s Control Over Authority

Coloniality’s control over authority via the state has led to the creation of a range of totalising institutions and accompanying professions to act as agents of the state to tackle the drugs and crime problems. For example, we have seen the creation of the treatment clinic and the prison as places of pathologisation and exclusion that permits specific sub-sets of the population to be marginalised and separated out from the rest of society. As a result of engagement in such institutions, structural factors and forces have been engineered to ensure that there are ongoing consequences, barriers and stigma which seek to limit their pathways into the community for a long time after they leave. Further, coloniality’s control over subjectivities has undermined a subject’s sense of self-authority and self-worth in relation to their being, sensing and thinking. Hegemonic narratives imbued with notions of hierarchy and value, have validated some sub-sections of the population forms of being, sensing and thinking whilst negating it for other sub-sections of the population.

Coloniality’s control of subjectivities

Dimou highlights the role of coloniality in downplaying non- western knowledge forms and practices, stating that

“it maintains the intellectual violence of colonialism through the discrimination and denial of any alternative ways of thinking, knowing, and being in the world” [3].

The systematic oppression and delegitimization of alternative ways of thinking, knowing and being has esteemed certain voices and perspectives whilst marginalising and silencing others to the detriment of knowledge production.

The theorists discussed above emphasize that ideological, structural, social and economic forces shaped by coloniality lead to personal, social, and societal ills. In summary, the structural forces of coloniality have created a culture of negative features: of isolation, individualism, addiction, competition, inequality etc. (see Table 1 below).

| The Culture of Coloniality |

| Isolation |

| Individualism |

| Competition |

| Consumption |

| Self-Centredness |

| Limits on who can contribute and participate |

| Control |

| Homogeneity |

| Inequality & Social Injustices |

Table 1. The Culture of Coloniality.

Reducing the Impact of Coloniality During Recovery

Research by [19] have found that what works in addiction recovery at the personal level are a number of pull factors which act as ‘antidotes’ to earlier pains of addiction, recovery, and more precisely societal ills. The detrimental, marginalizing, and stigmatizing impacts of coloniality seem to significantly diminish across various life domains as individuals progress in their recovery journey. A notable distinction emerges between individuals in stable recovery (five years or more of continuous recovery) and those in early recovery (the first year) [20]. Patton found that those in early recovery often face a complex web of inequalities: social isolation, strained relationships, trauma, a sense of hopelessness, possess negative self-identities, unstable housing, unemployment, or low-paying jobs [21]. They often find themselves within subcultural lifestyles and encounter various forms of stigma. The influence of coloniality appears most pronounced in the early phase, as life in stable recovery looks dramatically different. Respondents reported lives that exceeded their wildest expectations and were better than their lives prior to substance use. Stable recovery includes supportive social networks, family reconciliation, possessing a sense of empowerment and vision for one’s life, and active community participation through various legitimate identities and roles like homeownership, employment, education, and community involvement, secure housing, meaningful employment linked to having a sense of purpose.

Quality of life studies in the UK and US, in contrast to some of the ills created by the structures and culture of coloniality discussed above, show that those in drug addiction recovery have better outcomes for quality of life and well- being especially when compared to the general population [22-24]. Recovery through the lens presented in these studies highlights that recovery should not be viewed as the elimination of an illness or pathology but rather as a process that produces long term well-being, growth, human development and flourishing.

A range of frameworks have been developed which measure and support progress during recovery and help to overcome harms. Recovery capital is a key framework that can both measure recovery progress and identify factors that support or hinder recovery progress [25]. Coined by [26], recovery capital encompasses internal and external resources enabling recovery initiation and maintenance. Best propose three core domains of recovery capital: personal (skills, capacities, resilience, mental health etc.), social (relationships, support, networks etc.), and community (possessing a sense of belonging and participation in the community and society, accessing resources like education, housing, employment, mutual aid groups etc). These domains form a holistic framework for identifying factors driving growth and accrual of recovery capital [27].

The CHIME framework was developed by [28] based on a meta-analysis review of effective interventions that supported mental health recovery. The outcome of their review produced CHIME, a five-part model which provides a framework to guide recovery interventions. CHIME is an acronym that stands for connectedness, hope and optimism about the future, identity, meaning in life and empowerment.

As a person builds new social connections in recovery they possess a sense of belonging. Through these new pro-social relationships hope is encountered as they see and hear from their peers that change and growth is possible. Over time new replacement identities are occupied because of engagement with this community and new meaningful activities which also create a sense of empowerment.

Research has shown that both frameworks, recovery capital and CHIME are active for and effective at the individual, social, programme and intervention and at the macro, systems, and community levels [28-30]. That is, just as a person may possess forms of recovery capital or one of all five elements of CHIME, so may a programme, a system or a community.

Method

The project was funded by the National Institute of Health Research as part of the European Recovery Pathways study (REC-PATH). The REC-PATH project used mixed methods across four countries (England, Scotland, Belgium, and the Netherlands) to explore recovery pathways from addiction [27]. The REC-PATH study hosted an online global conference in March 2021 whereby the academic team presented their quantitative and qualitative research findings from the 4 countries. Research participants from the study were also invited to the conference. During the event, the research team invited the research participants from the REC-PATH project and those in attendance who had lived experience of recovery into this project to help translate the research findings into a recovery capital framework of what works in drug addiction recovery at different stages of the recovery journey to support those who are on their own recovery journey. It was acknowledged that the REC- PATH project was one of the largest studies to be conducted in Europe and it also wanted to elevate the voice of lived experience as part of the research process and to ensure that the dissemination of the knowledge gained filtered as widely as possible to reach recovery communities and those on their own recovery journey.

Following the conference, fortnightly online meetings were held from May to November 2021. Each meeting was recorded.

As part of the project, participants had to decide upon three key areas during the process.

1. What are the key findings/messages from the research findings?

2. How can these key findings/messages be translated into a ‘language’/form that will connect with those in recovery? (e.g. words, images, audio, video etc).

3. What vehicle/medium should be used to communicate the messages? (e.g. physical hard copy, digital, online, in person event etc.)

The Drug Addiction Recovery Capital Pathways Co- Production Digital Resource was launched in January 2022 with an online event where all participants were invited to view the resource and hear from the participants. The resource can be viewed below:

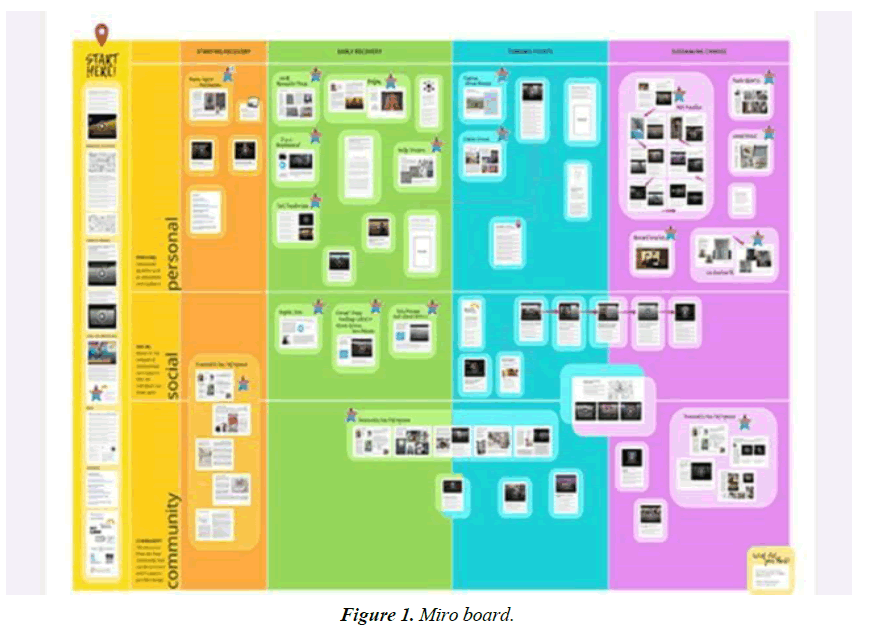

https://miro.com/app/board/o9J_ls4KMxY=/?invite_link_ id=766774058056 (Figure 1)

Qualitative thematic analysis was conducted [31] using both the transcripts from the recorded fortnightly meetings and also from the written contributions provided by each participant relating to the assets they submitted to the online digital resource. Themes were explored which related to the culture. of recovery. Culture is defined here as ‘the way of life’ of a particular community or group which encompasses their behaviours, beliefs, values, ideas, customs, institutions, tools, techniques, works of art, rituals, and ceremonies. NVIVO was used for the qualitative thematic analysis. NVIVO is a software package that allows the researcher to store, organize, and systematically analyse their qualitative data [32]. There is no pre-existing coding frame exploring the culture of recovery and so an inductive approach was taken during the open coding process whereby the dominant themes were coded that were repeatedly featured in the transcripts and in the written submissions accompanying the assets for the digital resource which related to their beliefs, values or behaviours/ practices. There was no attempt to generate an equal number of themes relating to values, practices or behaviours but rather to represent the dominant themes present. From the initial codes, themes were generated. Inter-judge agreement was checked at various points throughout the coding and analysis process. Co-authors three and four were present at the fortnightly meetings and they reviewed various iterations of the emerging coding and thematic frame and related analysis of the emergent themes throughout the coding and analysis process. Further, once the coding and analysis was complete, the authors presented the findings back to a sample of the respondents (as well as to others in recovery) to ensure that the themes used, and the analysis conducted matched the respondents' experiences and represented the culture of recovery. Positive feedback was received affirming the validity of the themes and analysis conducted.

Results

A total of 39 people participated (20 males and 19 females) and 9 Lived Experience Recovery Organisations and communities contributed to the project through their attendance at the fortnightly meetings and/or submitted one or more assets to the Drug Addiction Recovery Capital Pathways digital resource. The group varied in age from 23 to 69 with the median age being 45. 34 of the 39 were in recovery, of these only 3 were in early or sustained recovery with the remainder being in stable recovery. All participants were white.

The participants decided on a multi-media digital and online approach which featured a range of creative and traditional communication mediums. The digital resource presents a recovery capital framework of personal, social and community capital that was then broken down further by recovery stage, getting started, early, sustained, stable and turning points. 92 assets were contributed to the Drug Addiction Recovery Capital Pathways Co-Production Digital Resource. A wide variety of creative arts are presented: words, visual art, sculptures, mixed media compilations, songs, music, videos, and film. See Table 1 for a full breakdown of assets by media type. (Table 2).

| Asset Type | Count |

|---|---|

| Article | 1 |

| Blog | 3 |

| Book | 2 |

| Ceramic | 1 |

| Drawing | 4 |

| Graffiti art | 4 |

| MP3 | 3 |

| Painting | 23 |

| Photo | 6 |

| Podcast | 2 |

| Poem | 3 |

| Sculpture | 8 |

| Short Story | 2 |

| Song | 14 |

| Video | 15 |

| Workbook | 1 |

| Total assets | 92 |

Table 2. Assets contributed to the Drug Addiction Recovery Capital Pathways Co-Production Digital Resource.

One of the recovery communities that contributed a range of assets to the drug recovery digital whiteboard project ‘welcomes those suffering from drug addiction and marginalisation, and helps them to once again, find their way.’ The results presented below is an attempt to describe some of the features of the culture of recovery by highlighting the dominant beliefs, values, customs, and practices expressed. Whilst each person’s recovery pathway is unique and personal to them, the commonalities of what works in recovery from a range of mechanisms and pathways are drawn upon to explore if we can begin to describe a culture of recovery. As demonstrated in the results below, the culture of recovery is not confined to the submissions to the digital asset resource; it also permeated the dynamics, values, beliefs, practices, and discussions in the fortnightly meetings shaping the relationships, the hierarchies, the decisions made and the nature of the discussions that occurred.

Recovery as the Antidote to the Damage Caused by Society

There was an awareness amongst some of the participants of the negative macro, structural factors that contributed to their lived experiences of inequality and dire life circumstances. ‘Many of us grew up and were damaged by the society we grew up in. We have had to live and work within the patterns and rules and spaces that we wound up in.’ However, they went on to acknowledge that ‘Yet despite all that, there exists a tremendous path for healing.’ Another participant observed that the practices within the culture of recovery counteracted the damaging effects of these macro, structural and systemic factors and forces ‘people self-medicate due to what is going on in society but then people can start to make informed decisions about how they use the tools of recovery as antidotes to that, or how they use the tools of recovery as a treatment to that.’ This prompted another to state, ‘I believe that we are creating a message about what the antidote of recovery can and does look like. Having this antidote means that addiction can be recovered from.’ In this sense, recovery as expressed through the participants is a collection of values, beliefs and practices which helps redress the negative structural elements of society with its own set of values, beliefs and practices. Participants felt that through the project and the creation of the asset-based drug recovery digital whiteboard they were as one participant framed it, ‘building a sort of a map’ highlighting the way of life in recovery.

Empowering Beliefs to Create Change

Several empowering beliefs are evident within the recovery community. Whilst many of these empowering beliefs are demonstrated within the practices of recovery, and are discussed throughout this article, a number were also explicitly discussed at the fortnightly meetings or written about in the submissions to the digital resource. A strong belief was discussed relating to their faith and belief in the potency of the culture of recovery, simply stated by one participant as, ‘What we have works! Unlike many of the practices and beliefs in society’. Due to the strength of the belief in the potency of recovery, participants shared that, ‘we have the possibility to create change and actually show those who are in power, actually you’re missing a trick here by not allowing us to do what we do because it works.’ This was a commonly held belief by participants which also revealed a shared experience of their lived experience knowledge base and perspective being marginalised from a range of stakeholders within mainstream systems. Despite this, their belief in the effectiveness of the practices of recovery were unwavering. As another participant stated, ‘I have the privilege to be amongst people who believe things that I believe and want to do the things that I want to do. And it’s always interesting to hear people who have, you know, the belief that things can be done and done differently.’ As a result of the collective belief of the effectiveness of recovery practices, was the belief that therefore ‘we can affect change in society and help people.’ They recognise that the culture of recovery is transformative and can spread and be of benefit to others.

The participants were aware that the culture of recovery represents an alternative to the status quo in society and there was an acknowledgement that ‘what we’re imagining at this point is fairly new.’ This alternative culture envisions something new due to its possession of a different lens and accompanying practices. This radical envisioning was echoed by another participant who stated, ‘I think there is a genuine desire to create something that’s not been done before, and it has the potential to create such a positive and profound impact to change the trajectory for other people on their recovery journey.’ The responses here highlight the need for wider dissemination of the alternative practices of recovery to help normalize innovative recovery practices within society.

Recovery Customs and Practices

A range of norms, customs and practices were expressed by participants. These informed the habits, daily/weekly practices, the tools they used in their recovery that made up the expression of their everyday life.

Creative Expression

The culture of recovery is creative. Creative expression ‘has always been seen as an essential part of the recovery process’ (Communita San Patrignano). Creative expression in its myriad of forms (from creative writing: poetry, short stories, painting and drawing, song writing, performance to pottery making and fabric weaving and others.), is a core practice of recovery. As described below it serves as an essential tool for healing, promoting increased self-awareness, processing current and past events and emotions. Also, as the recovery journey progresses, this develops further and creative expression promotes a sense of purpose so that the creative artifacts produced oftentimes possess a message. Creative expression as a form of meaningful activity becomes linked to a sense of purpose which aids feelings of fulfilment.

Creative expression is also seen to have a redressing quality to it, as one participant observed they ‘use creativity and artistic expression to empower’ and to redress the harms created by society ‘because they are often unable to express their uniqueness and feel misunderstood and unaccepted in society.’ Thus, creative expression was seen by some of the participants as a practice that is a key antidote to negative factors in society.

Creative Expression as a Practice of Healing

Many who submitted assets to the co-production digital whiteboard project used a range of creative practices which increased their recovery capital, aided their personal healing in their recovery journey leading to empowerment, liberation, transformation, acceptance, better relationships with others and a new sense of self.

Writing

Writing is a practice and a core medium for creative expression, healing and transformation during recovery. New understandings of self and identities were created as a result. Karen ‘found writing incredibly cathartic, and I had so much to unravel, that I just couldn’t stop. I turned the light on to my demons so they couldn’t talk to me anymore... I wrote like my life depended on it. I saved myself... Once my story was on paper, I saw myself differently, instead of berating myself for my weakness. I realised I was an open and incredible, strong human being. It changed my life.’ Similarly, Helen shared how she loves putting ‘pen to paper and taking it for a walk. It may be in doing a page in my journal to explore how I’m feeling and ask for clarity in something I’m not sure about. Resting my big emotions on the page gives me so much serenity and peace in my heart, I am able to see, hear and express myself – without judgement. I’ve had to learn how to empower myself, and that judging part of me takes over.’ Writing as a practice of creative expression was key to generating increased levels of personal capital.

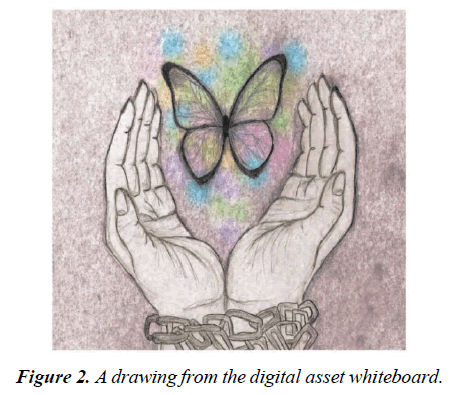

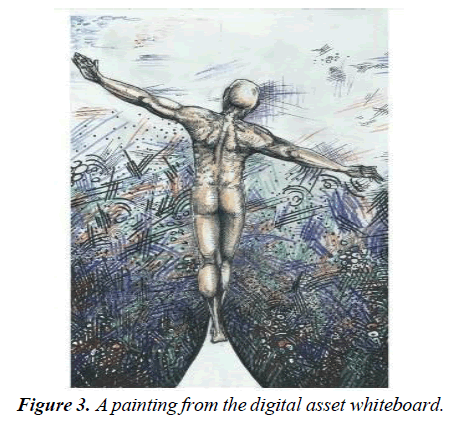

Drawing and Painting

Drawing and painting was another common practice in recovery which produced personal healing. Debbie shared how ‘learning how to draw and paint as an adult was a major part of my recovery journey and gave me back my confidence.’ Whilst this example shows how painting generated personal recovery capital and increased empowerment, some of the other painted assets on the board were used in exhibitions and for commercial sale to communicate positive messages about recovery and thus generated forms of social and community capital also. (Figure 2, Figure 3).

Drama and performing arts

Drama and performing arts were also a form of creative expression used in recovery. As one contributor to the digital whiteboard stated “Those with an interest can pursue theatre, music and dance often taking part in workshops with recognised professionals to improve their artistic skills. Something that they will keep with them for a lifetime. Theatre is an integral part of the therapeutic process for many residents as acting requires self-awareness and is a way to strengthen interpersonal skills.” Theatrical performances were often selected due to the potential therapeutic benefit for participants. For example, San Patrignano chose one particular play as it portrayed a man’s search for a real and meaningful life to echo those on the recovery journey. Drama and performing arts are key to generating personal capital and a sense of empowerment. New identity forms are created or consolidated from being an actor, a dancer and so on to replace older negative identities. Forms of community capital were also generated through the range of increased skills and experiences gained by participating in the productions but also through the engagement with those in the local community that watched the performances and the bonding and bridging capital that ensued.

Song

Songwriting was another key practice for several participants. Angela shared how ‘Music allows you to express yourself in ways that you may not have explored before. Group songwriting can bring people together and is a great way to hear each other’s thoughts and feelings. It can be a cathartic way to help with the recovery process, expressing yourself and hearing how others express themselves is a lovely way to support each other through recovery. Music is fun too! There is no right or wrong – just a space to be yourself. As a group, we were inspired to write about what we were passionate about, things that we feel are important and need to be heard. This was unity, equality and challenging stigma.’ The medium of music-making in a group over time not only led to personal healing and growth (personal capital), generating new identities of being a song-writer, but also reshaped the interpersonal dynamics promoting connection, unity and social capital. Importantly also, such spaces helped dismantle hierarchy and promote equality which can be a transformative experience. The group also developed a sense of purpose or mission with the songs helping to share messages that challenged the stigma that members had faced and thus created forms of community capital and empowerment.

Weaving

The creative act of weaving fabric was transformative for some of the participants. Ginevra shared how ‘weaving isn’t only my daily job. Weaving is what has helped me to have faith in myself again. It is how I have learnt to have relationships with people. It is how I’ve become freer to be myself.’ The benefits of creative activities include the generation of personal recovery capital via increased levels of self-belief and self-esteem including personal healing and liberation. They also extend to the meso-social level positively impacting relationships and social networks and thus generating social capital.

Creative Expression as a Vehicle for the Expression of Purpose and Supporting Others

Artistic and creative practices were not just for the individual's personal healing but also represented the expression of a sense of purpose and as a means of encouraging and supporting others. Tineke shared how her creative practices were more than simply creating objects but rather ‘I realised that this is what I really liked, making things with a message… My dream is making art, but first I had to take the path of life, to live my life, to make dreams come true!’ Similarly, many of the creative assets submitted on the digital whiteboard express a message by the artist, for example, when describing her painting of a lady entitled ‘Power Within’ stated ‘The message: That we all have a light within ourselves. We are wild and powerful beyond our knowing.’ At the heart of recovery is a range of creative practices whose purpose is also to support one another to succeed, grow, be liberated and reach their highest potential. Marcus described his poem as ‘A beacon of words calling for folk to keep strong on their march to freedom.’ AKA Mandilee describes the purpose of one of her songs is about ‘encouraging recovery, self- improvement, and actualization.’ Creativity is a vehicle for the expression of gifts, talents and strengths but also and importantly what is created as a result of these mediums is intrinsically connected to a deeper sense of purpose, community building and empowerment. Similarly, the most common reason participants gave for their involvement in the fortnightly meetings and co-producing the digital whiteboard was that it linked to a sense of purpose or as one participant framed it, they enjoyed being ‘involved with something bigger than me.’ Creative expression was key in generating recovery capital for the artist, and encouraging it in others. Elements of the CHIME model are evident for the person expressing their creative practice expressing a sense of purpose, providing meaningful activities and promoting a sense of empowerment.

Expressing Gifts, Talents and Strengths, and Creating Space for the Brilliance of Others

Recovery culture is a strengths-based culture. It enables and provides space and opportunities for people to discover and express their gifts, talents and strengths thus promoting feelings of empowerment. One participant shared that ‘every year they put on a thing called Recoveries Got Talent which involves people in recovery who write poetry, sing, play guitar and so on. And you realise there is a lot of hidden talent amongst people in recovery!.’ Communita San Patrignanoobserved that ‘A drug centred life is devoid of passion and leaves no room to cultivate talents. Therefore, in addition to the more traditional recovery driven activities, recreation and artistic pursuits can also be a valuable tool for self-discovery and growth.’ Richard made a key discovery ‘since getting sober in 2018, I discovered I could paint.’ For others, they had not used their talent whilst in active addiction and re-discovered their strengths and talents during recovery, for example, AKA Mandilee reflected that she ‘had lost her passion for music during her long battle with addiction but was inspired by her peers in rehab to pick up her guitar again’ and has gone on to release several albums during her recovery. Similarly, Scott reflected that ‘Graffiti art had been a passion of mine for many years, something which I put down in later years of active addiction and then found a love for once again, not long after entering recovery.’ The meaning and purpose derived from the discovery and expression of talents and strengths was a key cultural practice in recovery.

During one of the meetings one of the participants reflected on what works in recovery and emphasised the strengths-based approach in recovery and exclaimed that ‘it’s not about treating problems, but, instead, focusing on strengths and developing those strengths to empower the individual. If you focus solely on treating problems, you only find more problems.’ This led another participant to share that ‘I recently heard a definition of leadership which said that leadership is holding space for the brilliance of others! Which I just think the best thing, giving opportunities to people who are good at stuff to do the thing that they’re really good at which is what we are doing.’ This dynamic evident in the fortnightly meetings was also described by another participant, ‘here everyone fulfils their purpose and feel that they’ve got skills to bring and to use. It creates cohesion and cooperation.’ The effect of creating space for the contribution of gifts and talents was described as ‘giving voice to everybody and creating inclusivity and it changes the hierarchy.’ This dynamic in meetings promoted a sense of equality and power sharing that permitted everyone’s voice to be included via their participation of their gifts and talents. What is interesting here is that the expression of gifts is communal as opposed to an individualistic pursuit for personal gain or satisfaction. Rather, it is used to create community, promote inclusion and empowerment.

Generativity

The generosity of others to donate their assets to the asset based digital whiteboard was borne out of generativity and to help others consider the tools, practices and beliefs that they had found helpful on their journey in the hope that it may help others. Further, what was evident in the fortnightly meetings was a generous motivation to give back and to help others through their participation in co-creating the digital whiteboard. This generativity stands in stark contrast to a self-centred or even selfish mode of relating or doing that can be pervasive in society. As one participant shared, ‘I love contributing and being useful to the greater good. I am deeply of the belief that I get to keep what I’ve got by giving it away. This is a pay it forward principle.’ Similarly, another shared, ‘if I can help others, I know I’ve done my work. That’s what’s kept me going for a long time.’ And yet another shared, ‘the main focus of my doing whatever I do is to help somebody along the way. I love it when you see the light come on in their eyes.’ This intrinsic desire and motivation to help others and give generously created ongoing ripple effects or chains of support, for example, in one meeting a participant shared some recent feedback he had received from another which said, ‘Thank you for all you taught me. It has served me well on my own journey and helped me to give back to others.’ A shared form of recovery capital was created because of the generativity expressed. Empowerment is not just desired for the individual themselves but importantly also for others.

Values and Practices of Connection and Community

The culture of recovery is embedded within a connected and supportive community of people. Examples of this is also evident in other sections discussed above. Social recovery capital and community from the CHIME model are intrinsic to the culture of recovery. A dominant practice of recovery is the creation of strong social ties and positive supportive peer relationships situated in the context of a larger supportive community. Communita San Patrignano state that their community ‘is a community for life’ and have observed how for example their weaving laboratory ‘emphasises the value of the interweaving relationships between the girls, using the metaphor of the weft and warp in weaving. The interpersonal relationships were woven together during the course of their stay, working together in creating these amazing crafted items, created deep bonds that banished loneliness, and helped them get to know each other and support each other.’ Another participant also noted for him, ‘Addiction is not the problem. Addiction was the solution to the underlying problem and until I found some collaboration on how to fix the problem, I was just still treading water.’ Connection and supportive relationships within community is the environment in which recovery takes place.

Similarly, the need for connection and collaboration was a recurring theme throughout several of the fortnightly project meetings. One participant noted, ‘I believe we are making community and I also believe we are creating new possibilities.’ A sense of community and connected relationships were seen as the means by which progress would be made, one of the participants stated, ‘We should just use the hashtag together stronger. Because I can’t do it by myself, and you can’t do it yourself. So, we need to engage with each other and collaborate for this project to work.’ This promoted another participant to note, ‘We can’t change the conversations and challenge some of the stigmas that are still out there and get people talking about recovery and normalize the conversation unless we do it together.’ Another added, ‘For me it is all about building relationships in terms of how we get this message embedded in society and in services.’ Relational connection and community as a practice were mirrored outside of the individual’s recovery journeys as essential mechanisms for success and achievement during the meetings.

Hope as a Socially Transmitted Contagion

Possessing hope was central to those involved in the project. Hope was sparked and spread from person to person through hearing the recovery stories of others. As one participant described, ‘I heard someone tell their story about how they had used like I’d use and they didn’t use any more. And it was a revelation. It was the first time in my life that I realized that it may actually be possible for me to not do this anymore. I’d imagined I was some kind of a Keith Richards character and it would be a tragedy one day I wouldn’t wake up and everyone will be sad. And I felt I was fated. Another shared how hope was evoked for them when they realised that addiction ‘wasn’t a one directional journey. When I heard that there is actually a return to the journey, there is another direction that people can take, everything changed for me! The most powerful thing was to hear the personal experience of someone with lived experience and from someone who had found freedom from active addiction in whatever form that had taken.’ Hearing the shared experiences of others not only sparked hope but also built connection and community. As one participant explained, ‘I was grateful to discover that my experiences of recovery were so similar to other authentic experiences that people had in their recovery. Gaining this shared awareness helps all of us not feel isolated but rather helps us to gain confidence about our journey and increased my self-esteem. Contributing to this project has helped me in this way.’ Again the presence of the CHIME model (hope) is evident in this feature of the culture of recovery.

From the discussion above, several themes emerge as representative of a culture of recovery. (Table 3)

| The Culture of Recovery |

| Connection |

| Community |

| Collaboration |

| Creativity |

| Generativity |

| Contribution and participation |

| Liberation |

| Diversity/Heterogeneity |

| Equality & Social Justice |

Table 3. Some of the dominant features of the culture of recovery.

Discussion

The article has mapped out some of the features of the culture of recovery. A culture of recovery exists via its distinct array of norms, values, beliefs and practices. It is evident that it is a strengths-based community culture that is centred around authenticity, purpose, creativity, empowerment and generativity. The expression of these features enabled people to build recovery capital in a range of domains from personal, social and community. For example, increased self-awareness, self-esteem, personal healing etc. was gained through the practices of the culture of recovery. Positive and supportive relationships were cultivated due to the values, beliefs and practices of the culture of recovery. Further, bonding and bridging capital was generated with members of the community, it’s assets and resources through the practices of recovery culture. There was also a strong overlap between the features of recovery culture and the CHIME model. For example, there was a very strong emphasis on connection and community which both provide the context in which recovery occurs but also ongoing human flourishing. Hope as a socially transmitted contagion highlighted a fundamental feature of the culture of recovery. It is a culture that expresses and seeks to inspire and instil hope with others not just in relation to substance use but also in relation to a desired future self and life. The expression of gifts and talents in their creative activities were imbued with a deep sense of purpose and provided a deeper sense of meaning to activities. The net effect of the culture of recovery was that participants felt empowered, were active contributors and participators in their local communities, places of employment, on this project and so on.

This article set out to explore some of the features of a culture of recovery. What then emerged from the findings was how these features are the opposite of those created by the structures of society (See Table 4). The culture of recovery, emphasising connection, community, collaboration, creativity, hope, healing, liberation, empowerment and purposeful contribution. These features stand in opposition to individualism, competition, consumption, isolation, and control promoted by the triune forces of coloniality, capitalism and positivism which have detrimental outcomes for members of society relating to addictions, health and well-being, familial and social ties and participation in society. (Table 4)

| The Culture of Coloniality | The Culture of Recovery |

|---|---|

| Isolation | Connection |

| Individualism | Community |

| Competition | Collaboration |

| Consumption | Creativity |

| Self-Centredness | Generativity |

| Limits on who can contribute and participate | Contribution and participation |

| Control | Liberation |

| Homogeneity | Diversity/Heterogeneity |

| Inequality & Social Injustices | Equality & Social Justice |

Table 4. Recovery culture as a series of antidotes to coloniality.

When comparing the features of both cultures side by side, their contrary nature is apparent, with column 1 representing the negative pains of coloniality, and column 2 embodying factors for positive change. To recover from addiction pathways, it seems that they are also overcoming the pains of coloniality and capitalism. This suggests that the features of the recovery culture potentially could serve as antidotes to coloniality. The sample, perhaps unintentionally and unconsciously, revealed a collective vision for addressing societal ills and inequality. Therefore, we argue that the culture of recovery is a form of decoloniality and a challenge to neo-liberal systems. If this culture spreads beyond those in recovery it offers a potential pathway to extend this collectivist culture and it’s benefits beyond the confines of recovery itself.

Research studies increasingly emphasize the social and societal dimensions of addiction and recovery, aligning with the findings of this study. It appears that the frameworks of recovery capital and CHIME are active and operating at the macro and cultural level. Best suggested that CHIME can occur at a more macro systems level and not just a programme or interventions level. The results presented in this study, provide support for this idea given that features of community and connection, hope, empowering beliefs, expressing a sense of purpose etc. evident within the culture of recovery [30]. Further, Recovery capital and CHIME are regarded here as decolonial frameworks as they point to the existence of an alternative way of life to the one created by coloniality. They emphasize the potential for a transformative cultural shift away from colonial norms and values.

At the conceptual level, future research needs to develop a more comprehensive understanding of addiction and recovery by adopting a conceptual framework that incorporates macro, structural, measure and cultural dimensions. This should be accompanied by the creation of tools for operationalizing these concepts to monitor recovery progress effectively. Furthermore, there is a need for in-depth exploration of the features of the recovery culture to fully grasp its complexity and nuances. The current research, based on the experiences of individuals in recovery, provides an initial glimpse into these features and might have inadvertently identified structural and cultural antidotes. To build on this, future research should adopt a cultural perspective to investigate how personal recovery journeys intersect with cultural capital and their impact on social and structural change. Additionally, it's important to explore whether recovery practices, while individual in nature, inherently possess political and transformative dimensions at the community, neighbourhood, and societal levels. This would involve examining how recovery contributes to addressing structural and cultural issues through its spread and ripple effect within communities and society at large.

There are clear implications for policy and practice. It has been shown that lived experience is at the core of recovery culture, underscoring the importance of legitimizing and validating this form of knowledge to inform policy and practice approaches. Drug policy should integrate lived experience voices and knowledge, particularly from populations marginalized by coloniality, into drug and recovery policies. These populations hold transformative potential to help policy makers create new pathways within society which may benefit those in recovery as well as the general population.

Current efforts prioritize transitioning individuals away from addiction and enhancing treatment and recovery services. However, this research highlights that these approaches, while valuable, may fall short in harnessing the transformative power of embracing a recovery culture perspective. To address this gap, professionals in recovery and treatment should adopt a cultural lens, incorporating cultural elements into recovery planning expanding their focus beyond individual and service-oriented aspects.

Coloniality, primarily through its promotion of positivism, has systematically discredited and eroded the knowledge forms within recovery communities [1]. A shift is needed to rebalance the overemphasis on positivistic paradigms and approaches. Marginalized populations, who have been adversely affected by coloniality, are pivotal in liberating society from its detrimental effects. Among these populations, individuals in drug addiction recovery represent a segment whose cultures are poised for transformative impact in the coming decades, as collective efficacy and knowledge mobilization continue to rise. It's important to acknowledge that this transformation will take time. Alexander believes that social change and ‘society will change at a gallop when its world view changes, but its worldview will not change until a galvanising alternative philosophy appears, together with images, ceremonies, music and metaphysics that can give it life in human hearts and minds. The ability to create these magical pieces of the puzzle lies miles beyond the prosaic imaginations of rationalistic academics like myself [1]. The talented people who can produce them intuitively will materialise, as others have in previous eras of despair and confusion. We can only hope that they will appear sooner rather than later and that we are able to recognise them when they do.’

They are here, are we able to recognise them?

References

- Alexander B. The globalization of addiction: A study in poverty of the spirit. Oxford University Press; 2010.

- Mignolo W. The darker side of western modernity: Global futures, decolonial options. Duke University Press; 2011.

- Dimou E. Decolonizing Southern criminology: What can the “decolonial option” tell us about challenging the modern/colonial foundations of criminology?. Crit Criminol. 2021;29:431-50.

- Maldonado-Torres N. On the coloniality of being: Contributions to the development of a concept. Cultural studies. 2007;21(2-3):240-70.

- Quijano A. Coloniality of power and Eurocentrism in Latin America. Int Sociol . 2000;15(2):215-32.

- Sing, N (2022) Gabor Maté Wants to Overhaul Society. The Walrus.

- Maté G. The myth of normal: Trauma, illness, and healing in a toxic culture. Penguin; 2022.

- Russell C, McKnight J. The Connected Community: Discovering the Health, Wealth, and Power of Neighborhoods. Berrett-Koehler Publishers; 2022.

- Putnam RD. Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. Simon and schuster; 2000.

- Gov.uk (2018) PM launches Government’s first loneliness strategy; Society & Culture: London

- Jopling K. Combatting loneliness one conversation at a time: a call to action. Jo Cox Commission on Loneliness; 2017.

- Murthy V. Work and the loneliness epidemic. Harvard Business Review. 2017;9(1):3-7.

- Russell C, Burnett S, McKnight J. We don’t have a health problem, we have a village problem. Community Med. 2020;1(1):1-2.

- Hooks B. All about love: New visions. 2000.

- Block P, Brueggemann W, McKnight J. An other kingdom: Departing the consumer culture. John Wiley & Sons; 2015.

- McKnight J, Block P. The abundant community: Awakening the power of families and neighborhoods. 2011.

- Carlton B, Baldry E. Therapeutic correctional spaces, transcarceral interventions: Post-releaes support structures and realities experienced by women in Victoria, Australia. InWomen exiting prison 2013 (pp. 56-76). Routledge.

- Scraton P. Bearing Witness to the ‘Pain of Others’: Researching Power. InViolence and Resistance in a Women’s Prison’. Plenary Keynote at the 8th Annual Australian and New Zealand Critical Criminology Conference, 2014.

- Patton D, Best D. Motivations for Change in Drug Addiction Recovery: Turning Points as the Antidotes to the Pains of Recovery. J Drug Issues. 2022:00220426221140887.

- Panel TB. What is recovery? A working definition from the Betty Ford Institute. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2007;33(3):221-8.

- Patton D, Best D, Brown L. Overcoming the pains of recovery: the management of negative recovery capital during addiction recovery pathways. Addict Res Theory. 2022;30(5):340-50.

- Hibbert LJ, Best DW. Assessing recovery and functioning in former problem drinkers at different stages of their recovery journeys. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2011;30(1):12-20.

- Collins A, McCamley A. Quality of life and better than well: a mixed method study of long-term (post five years) recovery and recovery capital. Drugs and Alcohol Today. 2018;18(4):217-26.

- Valentine P. Peer-based recovery support services within a recovery community organization: The CCAR experience. Addict Res Theory. 2011:259-79.

- Best D, Irving J, Collinson B, Andersson C, Edwards M. Recovery networks and community connections: Identifying connection needs and community linkage opportunities in early recovery populations. Alcohol Treat Q. 2017;35(1):2-15.

- Granfield R, Cloud W. Coming clean: Overcoming addiction without treatment. NYU press; 1999.

- Best D, Laudet A. The potential of recovery capital. London: RSA. 2010.

- Leamy M, Bird V, Le Boutillier C, Williams J, Slade M. Conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health: systematic review and narrative synthesis. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(6):445-52.

- Best D. 2019. Pathways to recovery and desistance: the role of the social contagion of hope. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Best D, Colman C. Let’s celebrate recovery. Inclusive Cities working together to support social cohesion. Addict Res Theory. 2019;27(1):55-64.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77-101.

- QSR International. (2022). Unlock insights in your data with powerful analysis. Qualitative Data Analysis Software.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref