Research Article - Journal of Primary Care and General Practice (2020) Volume 3, Issue 1

Perspectives on Delivering Long-Term Services and Supports in Rural Washington State.

Tianna Fallgatter, Suzanne J. Wood*, Paul A. FishmanDepartment of Health Services, University of Washington, Seattle, WA

- Corresponding Author:

- Suzanne J. Wood, PhD, MS, FACHE

Department of Health Services,

University of Washington, Seattle, WA

E-mail: sjwood@uw.edu

Accepted date: July 01, 2020

Citation: Fallgatter T, Wood SJ, Fishman PA. Perspectives on Delivering Long-Term Services and Supports in Rural Washington State. J Prim Care Gen Pract 2020:3(1):4-13.

Abstract

This study explores stakeholders? perceptions regarding factors that promote or impede progress on a sustainable solution for delivering Long Term Services and Supports (LTSS) in rural Washington State. Our examination may signal to Community-based Long-term Care Network (CBLTCN) members and policy makers which LTSS priorities should drive future reform efforts. Using Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) eligibility criteria, we identified ten CBLTCN-member Public Health Districts (PHDs) classified as Critical Access Hospitals (CAHs), three regional representatives from Area Agencies on Aging (AAA), and three additional state government informants for participation in this study (n=16 representing a total population of about 213,000 Washington residents). The resulting geographic distribution represented variations in the State?s rural populations. Drawing from the Nevada Department of Health and Human Services Comprehensive Gaps Analysis of Behavioral Health Services (2013), we then employed a semi-structured interview instrument. Results of this study uncovered perceived gaps and strengths among the CBLTCN members. Associated interviews supported key assumptions from the literature about barriers to access and challenges facing rural health systems. Identified also were emerging themes, which differed by stakeholder level, local, regional, and state, and required further examination. Thematically, select results pointed to a lack of transportation options and the need for behavioral health providers, workforce challenges and budget limitations, and requirements for increased cultural competence and organizational efficiency. Our findings indicate no two CBLTCN members are identical but the struggles they face are almost universal, thus the environment has prompted efforts to develop creative solutions for immediate problems. Most PHDs believe that they can meet LTSS needs, yet resource shortages pose ongoing challenges. Future initiatives should include integration between rural PHDs and Home and Community Based Services (HCBS) to capitalize on existing structures and resources to stabilize Washington?s rural hospitals.

Keywords

Long-term services and supports, Qualitative methods, Washington State, Rural health care, Health policy.

Introduction

In 1980, the United States Congress passed the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act, allowing for the creation and reimbursement of swing beds for hospitals with fewer than fifty beds [1]. This program is geared toward addressing rural community’s unique needs and improving financial sustainability. It permits rural hospitals to receive reimbursement for long-term services provided in acute care beds. By 2008, 4.1 percent of the nation’s rural counties had no other form of postacute or transitional care [1,2]. Shortages of alternative forms of long-term services and supports (LTSS) can cause individuals to remain hospitalized for costly skilled aftercare rather than transition to skilled home and community-based services. Finding the appropriate care for patients who are unable to transition back into the community can be difficult and hospitals end up holding patients, sometimes several days or weeks after being considered medically rehabilitated [3].

LTSS comprise a group of services provided to older adults and people with disabilities. These individuals often need assistance because of limitations that restrict their ability to care for themselves [4]. Age and health conditions, including developmental, cognitive, functional, or chronic disease, may require paid or unpaid assistance for several weeks, months or even years [5]. LTSS includes institutional care, such as skilled nursing homes or long-term care facilities as well as home and community-based services. HCBS include assistance with activities of daily living (e.g. cooking, grooming, and eating) and may also include skilled care: home health and rehabilitative therapy [4]. Hospitals play a critical role in providing access to health care in rural America. In some geographically isolated communities, the hospital is the sole source of LTSS.

Washington State and LTSS

Washington State has been a change leader, shifting LTSS delivery from institutional to the community care setting. Realizing both the cost savings and human benefit of these efforts (e.g. improved quality of life, aging in-place), Washington spent almost 71 percent of its LTSS Medicaid budget on HCBS [6,7]. This is significant when compared to the national average of 52 percent [6]. “Presumptive Eligibility and CARE Assessment Tools” as well as the Money Follows the Person Program are examples of LTSS programs that have contributed to greater access to patient-centered care for Washington’s older population [8]. Despite these successes, developing capacity for LTSS in geographically rural regions of the State has remained elusive. Pressure to address the issue, particularly in Washington’s rural setting, has led to a collective call to better understand: What do local stakeholders perceive as factors that promote or impede progress on a sustainable solution for delivering LTSS in rural Washington State?

In May 2017, the Washington Health Care Authority (HCA) released “A New Vision for Rural Health in Washington” which outlined the current state of rural communities and a plan of action to address the unique challenges of individuals and the health care delivery system [9]. In addition to this rural vision, Washington was recently awarded a Medicaid transformation waiver. Initiative two of the waiver demonstration focuses on improving LTSS for Medicaid recipients [10]. Complementing State reform efforts, a group of rural public hospital districts (PHDs), in partnership with the Association of Washington Public Hospital Districts (AWPHD), and the Aging and Long- Term Support Administration (ALTSA), met to identify ways to slow erosion of LTSS, and build capacity for the spectrum of long-term care services. This was the beginning of the Community-based Long-term Care Network (CBLTCN), a network of ten rural hospitals who operate both institutional and/ or community-based LTSS. As the network begins the process of establishing its mission and future goals, the CBLTCN seeks to identify opportunities for cross-organizational collaboration. Furthermore, CBLTCN aims to contribute to reimbursement reform efforts by developing a new LTSS delivery model for improving access to the spectrum of LTSS for rural Washington State and leveraging best practices for rural service delivery.

Developing a strategy for LTSS sustainability in rural Washington

To aid the network in these efforts, this study seeks to identify perceived gaps in community care delivery and crossjurisdiction commonalities to identify the highest priority areas for state policymakers as they contemplate best practices for rural LTSS, and to assist the CBLTCN in establishing opportunities for improved collaboration. The purpose of this study, therefore, is to explore stakeholders’ perceptions regarding factors that promote or impede progress on a sustainable solution for delivering long-term services and supports (LTSS) in rural Washington State with emphasis upon the following research questions:

1. What similarities and differences exist among participating rural public hospital districts that comprise the CBLTCN?

2. What resources are needed to strengthen the rural LTSS continuum and encourage the use of community-based services when best suited to the patient’s needs?

3. Which best practice tool or model incentivizes greater use of community-based services without compromising the sustainability of other essential health care services in rural Washington?

Methods

The study team and research approach

This eight-month research study was conducted in collaboration with AWPHD, a partner organization whose membership included participating PHDs and associated organizations and who desired to understand more fully conditions that affected LTSS in rural Washington State. The research team included a female public health researcher who ran the project under the direction of two research professors, one female and one male, with over 40-years combined experience in health systems inquiry with specialization in systems management, strategy, economics, and service delivery. The principle investigator had weekly, sustained contact with AWPHD Regarding this project over the 2017 study and reporting period

Setting

Most rural areas shared commonalities such as, smaller population, travel distance between daily activities and reduced access to larger cities (The Rural Data Portal., n.d.). Researchers have historically used a variety of methods to classify geographically rural areas. For the purpose of this study, the Rural-Urban Commuting Area Codes (RUCA), developed by the Office of Rural Health Policy and the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service, was used to determine rural classification because it used census tracts rather than county level data to determine rural status (The Rural Data Portal., n.d.). Using RUCA methods, the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) identified counties and census tracts eligible for rural grants [11]. Nine of the counties in the CBLTCN qualified in their entirety. One county had two rurally designated census tracts; these two tracts fell within the geographic area of the PHD included in this study. Furthermore, all ten PHDs were classified as Critical Access Hospitals (CAH) (Washington State Department of Health, n.d.; US Health Resources & Services Administration, 2017). The resulting geographic distribution included regions in Eastern, Northwest, and Southern Washington State, thus providing a relatively even representation of the varied rural populations throughout the state.

Participant recruitment

Under the direction of two senior researchers, the principle investigator, in collaboration with the AWPHD partner organization, first identified study participants using purposive sampling [12], of select primary stakeholders at three levels: (1) local executives with PHDs and a skilled nursing facility (SNF), primarily those involved with the CBLTCN; (2) regional administrators from Area Agencies on Aging (AAA); and (3) state government officials (n=16 representing a total population of about 213,000 Washington residents). The team then contacted informants via email and telephone to request study participation and conduct telephonic interviews lasting 45 to 80 minutes, which were recorded and transcribed (Table 1).

| Organization Type | Participant Department | Participant Role |

|---|---|---|

| Local PHDs, n= 9 | Administration | Executive leadership |

| Local SNF (ECS Program*), n= 1 | Administration | Owner and operator |

| Regional AAAs, n= 3 | Administration | Executive leadership |

| State DSHS, n= 1 | Management Services Division | Operational support for ALTSA, rates management, and fiscal and contract management |

| State DSHS, n= 1 | Home and Community Services | Provision and administration of LTSS. Collaboration with regional agencies |

| State/Federal DOH, n= 1 | Rural outreach | Rural workforce development, population health, HIT consultation, training and advocacy |

*The Expanded Community Services Program (ECS) provides for expanded mental health services in the LTC setting. Participants receive program participation incentives and an additional reimbursement rate.

Table 1: Summary of Study Participation (n=16)

Apart from two large outliers, the geographic size of each PHD was comparable (Table 2). Total PHD population ranged from approximately 8,700-74,000. One SNF respondent was located outside any of the ten PHD’s geographic area. Because this respondent represented an individual organization rather than a geographically defined district, demographic data was not comparable and was thus excluded from analysis. Perspectives, however, were relevant because this SNF met various RUCA classifications for rural and included a unique mental health offering, the Expanded Community Services Program (ECS). Expanded Services Facilities (ESF) were designed to improve reimbursement and access to essential services for complex patients: ESF use high staffing ratios, with a strong focus on behavioral interventions, to offer effective services to their residents. These facilities offer behavioral health, personal care services and nursing at a level of intensity that is not generally provided in other licensed long- term care settings (Washington State Department of Social & Health Services, n.d).

| Study ID | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 9 | 10 | 12 | 17 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| District Population | 23,606 | 74,244 | 12,868 | 11,762 | 11,211 | 14,035 | 21,783 | 11,025 | 23,721 | 8,705 |

| District Size in Sq. | ||||||||||

| Miles | 1583 | 1556 | 1777 | 3229.5 | 2515.5 | 1076.9 | 1089 | 1520.7 | 3586.5 | 2158.1 |

| Swing Bed Data | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 2017-2018 | ||||||||||

| Medicaid Swing | ||||||||||

| Bed Rates | $187.21 | $187.21 | $187.21 | $187.21 | $187.21 | $187.21 | $187.21 | $187.21 | $187.21 | $187.21 |

| Medicare Payments | ||||||||||

| of Net Revenue | * | 42% | 35% | 48% | 39% | * | 72% | 45% | 34% | * |

| Medicare | ||||||||||

| Advantage | ||||||||||

| Payments of Net | ||||||||||

| Revenue | * | 70% | 20% | 30% | 0% | * | 0% | 11% | 10% | * |

| Medicaid Payments | ||||||||||

| of Net Revenue | * | 11% | 12% | 17% | 0% | * | 13% | 5% | 10% | * |

| Apple Health | ||||||||||

| Payments of Net | ||||||||||

| Revenue | * | 15% | 21% | 5% | 4% | * | 4% | 17% | 26% | * |

| Private Insurance | ||||||||||

| Payments of Net | ||||||||||

| Revenue | * | 19% | 22% | 21% | 54% | * | 13% | 22% | 26% | * |

| VA Payments of | ||||||||||

| Net Revenue | * | 0% | 2% | 0% | 0% | * | 0% | 0% | 0% | * |

| Private Insurance | ||||||||||

| Payments of Net | ||||||||||

| Revenue | * | 5% | 1% | 5% | 3% | * | 11% | 1% | 3% | * |

| Hospital Operating | ||||||||||

| Margin/Cost | -18% | -14% | 7% | -10% | 11% | -10% | -15% | -8% | -9% | * |

| Nursing Facility | ||||||||||

| Medicaid Daily Pay | ||||||||||

| Rate | * | $169 | $150 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| Assisted Living | ||||||||||

| Facility Medicaid | ||||||||||

| Daily Pay Rate | * | $65 | * | $62 | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| Nursing Facility | ||||||||||

| Total Cost/Day | * | $394 | $223 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| Assisted Living | ||||||||||

| Facility Total | ||||||||||

| Cost/Day | * | $182 | * | $122 | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| Margin per Day | ||||||||||

| Nursing Facility | * | -39% | -4% | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| Margin per Day | ||||||||||

| Assisted Living | ||||||||||

| Facility | * | -57% | * | -27% | * | * | * | * | * | * |

Table 2: Summary of Demographic (2016) and Swing Bed Rates (CBLTCN Members).

Data collection

Understanding the CBLTCN members’ perspectives was key to identifying underlying issues for each community, which was of primary interest for this study. Subsequently, the research team developed a semi-structured interview instrument using key informant questions from the Nevada Department of Health and Human Services “Comprehensive Gaps Analysis of Behavioral Health Services” as a guide [13]. Questions were tailored to the topic and region(s) of interest (see Table 3) and tested for content validity with industry experts prior to conducting the first interview. Each participant was provided a working definition of the topic (LTSS) prior to the beginning of the interview. The LTSS definition, a compilation from several national and state agencies, such as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the Washington State Department of Social and Health Services (DSHS), and, more specifically, the Aging and Long-Term Support Administration (ALTSA), was designed to provide the broadest inclusion of all possible LTSS constructs. As per the University of Washington Institutional Review Board’s protocols, respondents consented, and interviews were recorded to allow for greater accuracy in transcription (Table 3).

| Topic | Target | Questions by Stakeholder Level |

|---|---|---|

| Research Question | ||

| Service delivery and gaps | 1, 2 |

|

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

| Sustainability | 1, 2 |

|

|

||

|

||

| Readiness to change | 1, 3 |

|

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

| Cultural awareness | 1, 3 |

|

|

||

|

||

| Collaboration efforts | 1, 2, 3 |

|

|

||

|

||

Table 3: Sample Interview Questions.

Data analysis

Transcriptions were de-identified and then imported into Dedoose® (v8.0.42) qualitative coding software for content analysis. Next, using the research questions as a guide, the research team created several a priori codes; for example, “gaps in service” or “community strength.” Using an abductive coding approach, two researchers then analyzed transcripts thematically by question, as outlined above, and secondarily using elements of the grounded theory approach to content analysis: open, axial, and selected coding [14,15]. The team initially coded independently, then validated coding by comparing both themes and results discussing in person any discrepancies or differences until reaching both consensus and saturation [16,17]. De-identified and aggregated results were then shared with the AWPHD partner who further validated findings (triangulation) and provided additional context [17]. In addition, the team sought to compare multiple case studies to uncover varied perspectives rooted in a specific context (LTSS in rural Washington State) to understand community needs [18].

Results

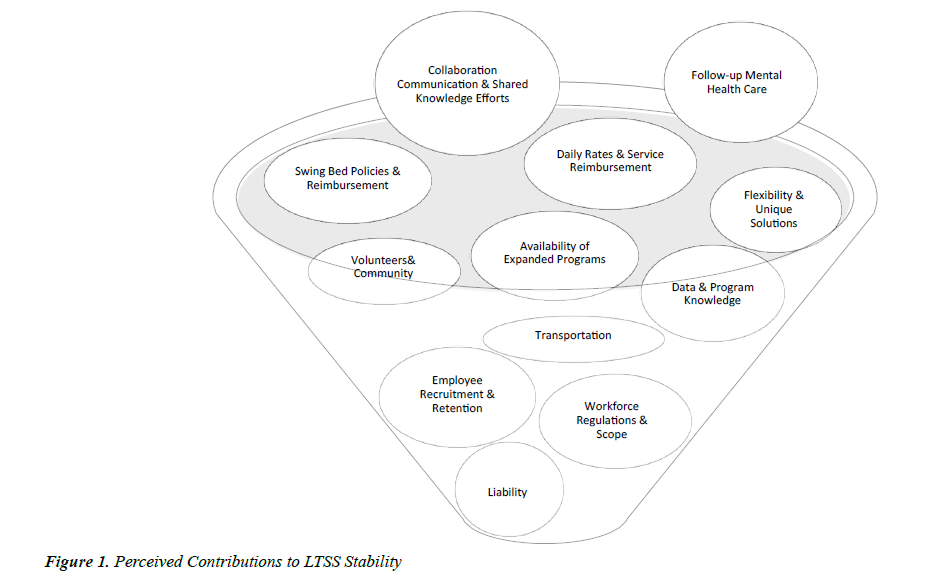

Results of this study uncovered gaps and strengths among the CBLTCN members. Interviews supported a priori assumptions and knowledge from the literature about barriers to access and challenges facing rural health systems. Emerging themes were also identified, which required further examination from three stakeholder levels: local, regional, and state. Figure 1 provides a summary of thematic findings resulting from this analysis, each of which are described in detail below (Figure 1).

Local level

Transportation as a barrier

At the local level, study participants identified transportation services as complicated and very limited. Some communities solely relied on volunteer drivers and others utilized the infrequent county provided services. One administrator described transportation as a critical piece of quality care in the community: “…but if it (transportation) isn’t available for that patient to be able to be sent home and still maintain scheduled appointments and what not, that may signal that the patient can’t be in the home environment at that point in time. And they would have to stay within some sort of institution setting…And, they really could have been discharged home sooner had there been some sort of transportation program available to getting them back and forth to their appointments correctly.” Another administrator discussed the challenges its volunteer drivers faced because of the long distance’s patients traveled to see specialists: “Transportation, it’s difficult to schedule. Most of these patients must go to (a city) to see specialists. And so, when you are talking about a three-hour round trip, plus wait times, plus doctor time, your day is shot. So, to schedule transportation with volunteer drivers or anything in life, that is challenging. And it’s costly.”

Creative solutions and unintended consequences

Many of the PHDs were already working in unique ways to meet community needs. For example, one PHD used their ED nurses to make home visits for patients unable to travel to appointments. These creative solutions also came with unintended consequences. One PHD provided complex wound care management to the community, but the demand for services was greater than the available employee work hours. So, the PHD faced balancing quality patient care with managing workforce burnout and overtime pay. Access to skilled home health varied by PHD but most all commented that although it was available it was not reliable.

The problem of delivering behavioral health services

Rural Washington PHDs have suffered from mental health provider shortages, “Yeah, it is a pretty significant failure on our county’s part to have those services available in mental health and psychiatry…even if you were to go to the closest hospital with psychiatric services right now…it is going to take me two months before they can get me in to see the psychiatrist for the first time.” Results showed that many PHDs had established teleconferencing, shared psychiatric nurses, or had access to emergency mental and behavioral health services through county resources. Yet, for individuals in need of follow-up after a crisis, most communities struggled with delivering timely care.

Rural health and swing beds

Most, but not all PHDs interviewed operated swing bed programs. PHDs operating both Swing Bed Programs and skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) were more likely to collaborate using information resources available to the community, informal and formal. Some PHDs demonstrated stronger ties and collaborative efforts with regional LTSS coordinators, but all expressed some level of cross-organization collaboration and a general willingness to do more. Limited time for external efforts was cited as a significant deterrent to greater collaboration: “‘we have meetings where we get together with all our partners and everybody gets a little piece of time. I would like it if we had regular monthly meetings just one-on-one. Our facility, with the aging and long-term care, I would like to see more regular or routine collaboration, so we touch base every month or every couple of weeks. Because if we don't do that, then there (are) people in the community that are going to slip through the cracks that we might miss. And if we had a regular meeting just one-on-one, we could probably better service that population”. With another administrator adding, “I think we all get busy and maybe it's hard to meet as often as we would like, or to talk as often as we should.”

Expanding LTSS in rural communities

Most PHDs expressed a willingness to expand their services, including HCBS, to meet community need and improve the LTSS continuum. Many had already taken either informal or more formalized steps towards developing an HCBS service line. PHDs that owned assisted living facilities were more likely to perceive expanded reimbursement of HCBS as a threat to their business model. Most other PHDs viewed it as a needed supplement to existing services. Many administrators viewed LTC swing beds and nursing facilities as a final stop for patients too critical to be cared for in their homes, “I don't know that home or community-based (care) would really affect the residents that we have. I think they are going to need a higher level of care than what is offered through those alternatives.” Most PHDs believed that while they could meet the LTSS needs of any community member in a timely fashion, shortages were still a problem.

Cultural competence and LTSS

There appeared to be a limited understanding of culturally sensitive care. When respondents were asked about culturally appropriate resources in the community, most responded with a description of translator services: “We have language issues here. You may have a person who speaks only Spanish. But they live in a home or are cared for by folks who only speak English. So, that can certainly be a barrier.” Alternatively, others stated that they had not yet found culturally competent care to be a problem, with one administrator sharing, “I don’t know that we have anything that specifically targets or caters to a diverse population. This part of the county is not very diverse so there have not been cultural centers that have sprung up or, I guess, (people who have) advocated for that. And the need has not really presented itself here, for us. To my knowledge it is non-existent.”

Regional level

Interviews and secondary data at the regional level provided further insight into local themes and uncovered emergent topics concurrently. Overall, at the regional level, delivery of LTSS was perceived as meeting the needs but not sustainable. Critical to improving access to HCBS in the most rural of regions were transportation and home health services, a finding that aligned with local level respondents. Cultural competence was not believed to be a challenge for most rural LTSS, particularly because family caregivers were available and because legislation mandated the provision of interpreters. One executive described common practice this way: “Oftentimes caregivers that are bilingual family members are available to be contracted. And that does provide a contact of the primary service that the individual is receiving by someone who is culturally consistent with that consumer. It is a primary strategy that is used throughout the State. It is not an adequate strategy for every consumer, and there is not an adequate supply of cultural appropriateness for every one of those unique cultures that we sometimes see. But, overall, our region is probably about 95% Caucasian. It is much higher than the State on average and so, we are less challenged by that…there are small numbers of non-English speakers and people of color in our region.”

Challenges extended beyond LTSS resources

One executive identified challenge that extended beyond elderly access to LTSS. They spoke of housing challenges, rising costs and reduced inventory combined with stagnant wages: “There is virtually no affordable housing. When you look at healthcare provision, the actual folks who provide the care, they are in the category of needing portable housing or subsidized housing is gone. And yet, you have an aging population.” Adding “…the reality is that we (rural areas) are quickly running out of affordable housing as well. And, in terms of public transportation for those who find themselves without resources or diminishing resources, or needing transportation to see healthcare providers, that is a huge challenge in rural areas. We simply do not have the resources that are, for instance, in downtown Seattle and even Bellevue. So, you see all these converging factors and the resources to meet a growing population are diminishing. So, we have some great challenges in long-term care and supports.”

Workforce challenges and budget impacts on rural LTSS

Another theme at the regional level was unpredictability in the rural HCBS workforce, which made timely delivery of AAA organized services a challenge. One respondent offered, “There is a certain churn in that workforce…that does create a certain amount of angst and wear and tear, and sometimes gaps for a period for that given consumer—separate from their acuity level changes. I do not want to leave you with the impression that people are without service all the time. I am just saying that some people have unique needs that aren't going to get met locally.” Common concerns included already tight budgets, future cuts and service mandates that limited discretionary spending and program flexibility for rural areas. One executive expanded upon the unique challenges rural areas faced in adhering to DOH guidelines: “The differences between the I-5 Corridor and the Mid-Valley up in (City X). Most of the rules of the Department of Health apply to both. But again, the ability to meet those rules and regulations and how we adapt to them; is probably one of the greatest challenges that I think our association is certainly struggling to figure out how to do.”

A lack of confidence as a barrier to HCBS

Regional executives discussed why uptake of HCBS had failed to meet expectations. Among the already identified barriers, one executive commented anecdotally on the lack of confidence rural communities and their providers place in home health services, “I have felt that in many cases in rural areas there may be a lack of confidence of home health actually following through. And, I think in the medical community and the doctor's world, there is still situations where, when there is a lack of confidence on the part of the primary care doc or the hospitalist, that home health is really going to be able to follow through, on monitoring and managing on a skilled task on a discharge, that their impulse is to keep the person (as an) inpatient. Because they feel that the risk is managed better. And, if home health doesn't perform effectively…there is a reputation issue that primary care doesn't feel confidence in.”

Continuing to state “…once that, that has been broken or not established, then there isn't confidence that service will be supported, and that patient will be well served. But the primary care still feels at risk about it and so they keep the patient in there [institution] until they feel confident that the discharge is going to hold water medically.”

State level

State level study findings suggested that HCBS resources were available in rural Washington. From this analysis, themes involving data, ageism, and system re-design emerged. One advocate spoke of access and anecdotal evidence of inconsistencies in data: “…When we look at the larger map of the State, I think we absolutely feel comfortable that there is access to (LTSS) services. Not nearly as much as we would like as a State, but we understand that in order to provide the access that everyone feels would be adequate it would probably double or triple our actual budget or something...When State officials are saying it’s probably not that big of a deal, it’s probably the viewpoint that as a whole the system is actually doing really well, especially when compared to other States. But, that means absolutely nothing if you are in a smaller community and all you see is a single resource and it is either overworked, or not available to you, or it is not the resource you actually want. I would guess it’s just different levels of perspective based on where you are actually sitting in the system.”

State officials perceived cultural competency, ageism, and racism to pose serious challenges for equitable access in rural communities. Concerns about cronyism and organizational conflicts were raised as significant barriers to future collaborative efforts and LTSS delivery system redesign across organizations and levels in particular, “...we have seen some pretty intense disasters from these boards (PHD Commissioners). Capricious firing of CEOs is one example, because they are scaring the board, because they are talking about the future. So, these boards of the PHD don't necessarily have modern thought about health care systems or aging systems. If it (service hub, new LTSS model were) to land there, they would need an enormous amount of training and facilitation of discussion. The lever for them…is they want to please their community. They don't want anybody to meet them at church on Sunday and say, ‘What the heck are you doing?’” Adding, “…there is a community engagement piece that may wrap around that and make it more feasible for a PHD.” State officials felt that communities supported any efforts that enabled family members to remain in their communities as they aged. Yet, AAAs and providers needed to collaborate for the purpose of integrating knowledge. There was recognition that for a new system to work, one entity had to take ownership of the effort; however, such ownership was likely better suited to a third-party entity rather than using local PHDs or regional AAAs. The reason was that PHDs needed to change their operational focus to realize, “…a very intentional integration of the aging spectrum of services and the Triple A influence.”

Supporting new LTSS delivery models

Also identified at the state level were new service delivery models, rates, and best practices. Respondents also raised questions about government efficiency and effectiveness, as every state-level respondent agreed that government-run programs were not the most efficient vehicles of change, but that their ability to persist long-term made them very effective programs. Repeated references to gaps in knowledge at different levels appeared to be a root cause of this disconnect. For example, one informant was unable to respond to a question about effectiveness of the programs approved by DSHS but managed by AAAs.

Limitations

The research timeline and budget constraints did not allow for the collection of all stakeholder perspectives identified as important for the discovery process. The detailed understanding each CEO had of internal patient operations varied greatly. Some of the hospitals identified additional knowledge resources (e.g. hospital nursing and social work staff) better suited to assist in answering remaining questions. These individuals were unresponsive to requests for information. Also, because of the diversity, geographic spread, and disconnected nature of HCBS, interviewing individual HCBS service providers or organizations proved to be unrealistic within the provided budget and timeline. As a substitution, regional AAA representatives were interviewed.

Discussion and Implications for Policy

The purpose of this study was to identify which elements of the current environment promoted or impeded progress on a sustainable solution for delivering long-term services and supports in rural Washington State. The secondary data analysis, combined with the various perspectives of key stakeholders provided evidence that policymakers and members of the CBLTCN could apply to future LTSS reform efforts in rural Washington, the focus of which is discussed in context below.

1. What similarities and differences exist among participating rural public hospital districts that comprise the CBLTCN?

2. What resources are needed to strengthen the rural LTSS continuum and encourage the use of community-based services when best suited to the patient’s needs?

3. Which best practice tool or model is best suited to incentivize greater use of community-based services without compromising the sustainability of other essential health care services in rural Washington State?

Assessing Similarities and Differences among CBLTCN Rural Public Hospital Districts

No two CBLTCN members are identical but the struggles they face are almost universal. This environment has prompted a variety of efforts at developing creative solutions to immediate problems. For most, these solutions, akin to temporary fixes, may not adhere to the strict rules and regulations for workforce or employee liability. This highlights the need for greater flexibility in using existing resources without penalty. Ensuring that allied health professionals can perform their duties to meet patient needs is essential to sustaining service capacity. Additionally, these services should be reimbursed based on the actions required, not on who performs the action. Quality metrics, when designed accurately, can ensure that a flexible approach does not adversely affect patient outcomes. Use of medical assistants and nurse assistants interchangeably in rural LTC could reduce the burdens associated with hiring two similarly trained individuals who perform similar duties in low census facilities. Reevaluation of existing laws on scope of practice combined with the ability to offer apprenticeships among CBLTCN members could bolster existing resources.

Very few of the PHDs have reliable, timely access to mental health services, but those who do have built strong mental health programs. This program knowledge or service could become a shared benefit within the CBLTCN. None of the PHDs are contracted with DSHS to receive additional reimbursement for mental health services through the Expanded Community Services Program (ECS). Consideration for how this program might benefit financial sustainability and fill a gap is needed. Because many of the CBLTCN members rely on swing beds to provide the community with LTC services, consideration of how this program could interact with the swing bed program should be evaluated. DSHS could for example, allow ECS programs to be established within a network (CBLTCN). This would allow use of existing CBLTCN resources and the costs of meeting the additional regulatory requirements could be shared among members—thus, reducing overall program costs.

There is an understanding that without the swing bed program, many communities would have no alternative options for institutional care. This program offsets costs incurred by operations and other service lines (e.g. ambulatory care). Acknowledgement across local, regional, and state stakeholders is important because almost all PHDs have swing beds, yet they are used differently. There is greater need to understand the nuances of swing bed LTSS delivery and how its use can be mutually beneficial to rural PHDs and the primary payers, Medicare and Medicaid. These efforts may benefit Washington by encouraging greater buy-in from CMS to payment reform efforts that directly impact Medicare, as with the use of a model like the Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly, PACE [19].

Members of the CBLTCN share a need to find workforce and build sustainable referral processes for employee churn. As a collective, the CBLTCN could advertise postings and develop stronger professional relationships with Allied Health Programs. Combining recruitment services and contract knowledge with a more balanced rural wage for support staff (across all CBLTCN) would reduce competition for resources by ensuring universal wages. Wage leveling and direct-line communication from a CBLTCN representative to programs could double as a public relations campaign and encourage program coordinators to promote rural employment more heavily. The effort, however, will not reduce workforce competition from more metropolitan health systems. To address this, the CBLTCN as a collaborative can lobby large institutions and allied health associations for more rural emphasis, and potentially more rural externships.

A communication effort across levels and among collaborators needs to be strengthened. This combined with a more comprehensive awareness of what specific services are offered by both PHDs and the HCBS providers in a single area could reduce confusion and mistrust and improve utilization of existing LTSS within each community. For example, the websites of all CBLTCN members are less comprehensive than the lists provided by administrators in interviews. Likewise, the information gathered from regional agencies is inconsistent with what was known by local administrators. Although this would not build additional capacity, having a universal resource for both HCBS and medical services, and making this resource match what is promoted on government and PHD websites, could improve community awareness and more clearly identify gaps in individual communities.

Most PHDs appear receptive to expanding their service line given the right financial incentive(s). However, none are willing to further jeopardize existing services to improve access in their communities. Discordance exists among respondents regarding culturally competent care and access for all community residents in need of LTSS regardless of payment type (e.g., M