Commentary - Journal of Gastroenterology and Digestive Diseases (2025) Volume 10, Issue 3

MRI diagnosis of a long cystic duct merging with the accessory pancreatic duct: A case report.

Ella-Ondo Timothée1*, Mba Angoue Jean-Marie Siégel2, Moulonda Bolo Gaetan1, Ollende Crepin3

1Department of Radiology, Akanda Army Training Hospital, Libreville, Gabon

2Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Akanda Army Training Hospital, Libreville, Gabon

3Department of Visceral surgery, Akanda Army Training Hospital, Libreville, Gabon

*Corresponding Author:

- Ella-Ondo Timothee

- Department of Radiology,

- Akanda Army Training Hospital,

- Libreville, Gabon

E-mail: thimotheeellao@yahoo.com

Received: 29-Jan-2024, Manuscript No. JGDD-24-126248; Editor assigned: 31-Jan-2024, JGDD-24-126248 (PQ); Reviewed: 14-Feb-2024, QC No. JGDD-24-126248; Revised: 11-Feb-2025, Manuscript No. JGDD-24-126248 (R); Published: 18-Feb-2025, DOI: 10.35841/jgdd-10.1.242

Citation: Timothée EO, Siege MAJM, Gaetan MB. MRI diagnosis of a long cystic duct merging with the accessory pancreatic duct: A case report. J Gastroenterol Dig Dis. 2025;10(1):242

Abstract

Anatomical variations of the extrahepatic bile ducts are multiple and better known since the advent of Bili-MRI. Their knowledge by radiologists and surgeons is essential in hepatobiliary surgery. A case of a long cystic duct merging with the accessory pancreatic duct has never been reported. Our observation concerns a 22-year-old girl in whom a short cystic duct filling the gallbladder from the intrahepatic biliary confluence and another long cystic duct merging with the accessory pancreatic duct was revealed.

Keywords

Bile ducts, Cystic duct, Anatomical variation.

Introduction

The anatomical variations of the extrahepatic bile ducts are numerous and better known since the advent of Bili-MRI, the technological performance of which allows anatomical mapping of the bile ducts [1-3].

The variants of the cystic duct [4-6] are related to the embryological mechanisms which occur between the 4th and 5th week of gestation [3]. Several variants are known but a long cystic duct merging directly with the accessory pancreatic duct has never been reported as is the case in our observation (Figures 1 and 2).

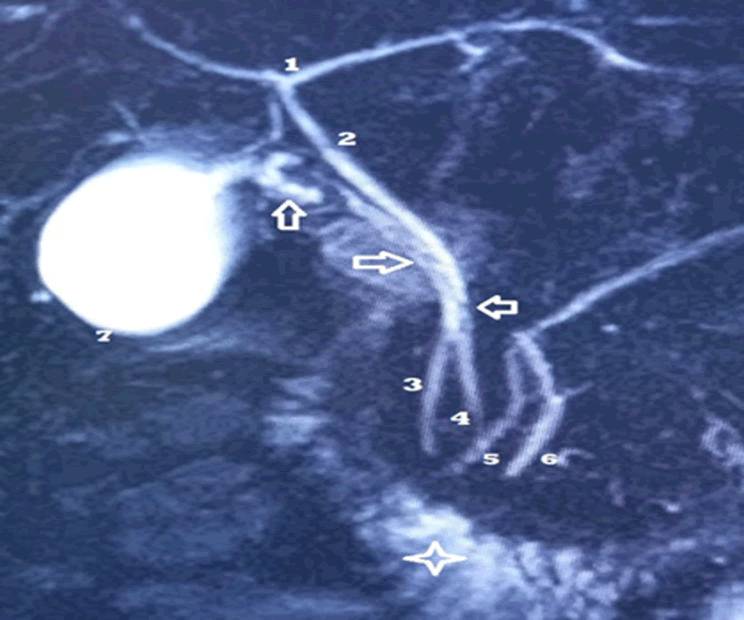

Figure 1. Bili-MRI of Miss O. Rachel. T2 HASTE 3D (MRI cholangiography).

The intrahepatic biliary confluence where an accessory cystic duct ends ensuring vesicular filling [1].

The common bile duct [2,3] with a regular wall without endoluminal defect is normal.

The gallbladder (7) is drained by another so-called main cystic duct (hollow arrows and 4) which crosses the main pancreatic duct to merge with the accessory pancreatic duct [5]. Note the disparities in caliber of the main cystic duct on the upper 2/3 of its course with multiple defects in relative hyposignal which may correspond to endoluminal mucosal folds of the cystic duct. No clear stone signal.

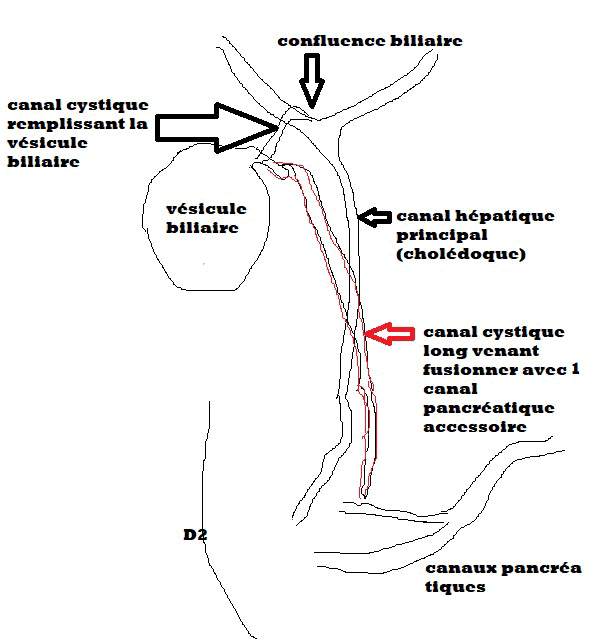

Figure 2. Schematization of our observation.

Case Presentation

Miss O. Rachel, 22 years old, was referred to our department for a Bili-MRI due to persistent pain in the right hypochondrium without obvious ultrasound or CT abnormalities.

The examination was carried out fasting according to a standard Bili-MRI protocol: 3D, T2 HASTE, SSFP and morphological scan of the liver.

This examination showed a normal intrahepatic bile confluence and a normal common bile duct. An accessory cystic duct connected the gallbladder to the intrahepatic biliary confluence and ensured gallbladder filling. The main cystic duct, with disparities in caliber on the upper 2/3 of its course and multiple parietal defects in relative hypo signal, crossed the main hepatic duct to merge with the accessory pancreatic duct.

Discussion

The extrahepatic bile ducts are the site of several anatomical variants which must be known to the radiologist and surgeon [4,7].

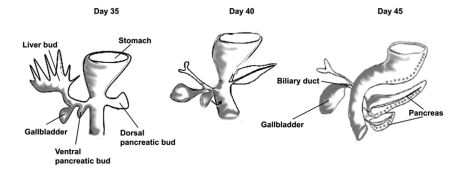

The buds of the liver, gallbladder and cystic duct appear from the 4th week of gestation near the ventral pancreatic bud. By a rotation mechanism, the cystic duct will then join the common bile duct (Figure 3). The variations in number, shape and arrangement of the cystic duct depend on the moment of separation of the hepatic and cystic buds which occurs at the 4th and 5th week. Early separation is responsible for a long cystic duct. Late separation is responsible for a short cystic duct or the absence of the cystic duct. The cystic duct then merges with the common hepatic duct. Depending on the point of this fusion, we obtain the anatomical variations of the cystic duct [3,8].

Figure 3. Embryologic development of the biliary tree and pancreas.

In our observation, the main cystic duct had merged with a persistent accessory pancreatic duct. The gallbladder was filled by another short cystic duct communicating with the intrahepatic biliary confluence.

The accessory pancreatic duct is inconstant and derives from the dorsal pancreas and drains the upper part of the head, ending at the upper part of the inner border of the second Duodenum (D2) by the small caruncle.

Considering the embryological mechanisms at the origin of the arrangement of the extrahepatic bile ducts [3], our observation is explained by a very early separation of the cystic and hepatic buds, a persistence of the accessory pancreatic duct and an early posterior rotation resulting in to the fusion of the bud of the main cystic duct with the persistent one of the persistent accessory pancreatic duct.

This is the first observation of a long cystic duct merging with the accessory pancreatic duct thanks to Bili-MRI which has established itself as the reference examination to visualize the arborization of the extrahepatic and pancreatic bile ducts, the knowledge of which is essential for radiologists and surgeons preoperatively [9].

Conclusion

In conclusion, this case report highlights an extremely rare anatomical variation of the extrahepatic bile ducts, where a long cystic duct merges with the accessory pancreatic duct. Such a variation has never been previously documented in medical literature, making this case particularly noteworthy. The patient, a 22-year-old female, presented with persistent right hypochondrial pain despite normal findings on ultrasound and CT imaging. The diagnosis was made through Bili-MRI, which revealed the unusual merging of the cystic duct with the accessory pancreatic duct, an accessory cystic duct connecting the gallbladder to the intrahepatic bile confluence, and a normal common bile duct.

The case emphasizes the significant role of advanced imaging techniques, particularly field of Bili-MRI, in identifying rare anatomical variations. Bili-MRI has become a valuable tool in the hepatobiliary diagnostics, providing high resolution, non-invasive imaging that can accurately depict the complexities of the biliary and pancreatic ductal systems. This advanced imaging modality is critical for preoperative planning, enabling surgeons and radiologists to fully understand the anatomical landscape before undertaking any surgical intervention.

Furthermore, the embryological basis for the formation of the bile ducts and pancreas provides insight into how such variations occur. The timing of the separation of the hepatic and cystic buds during fetal development plays a crucial role in determining the final anatomy of the bile ducts. In this case, an early separation likely led to the persistence of the accessory pancreatic duct and the unusual anatomical fusion observed.

This report underscores the importance of understanding biliary and pancreatic ductal variations for both diagnostic and surgical purposes. It also highlights the need for continued awareness among radiologists and surgeons about these rare anatomical entities to prevent potential complications during procedures such as cholecystectomy or pancreatic surgery. By documenting such rare cases, the medical community can further enhance the understanding of biliary anomalies and improve patient care.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the conduct of this work and also declare having read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- Nozha T, Abid H, Henchir S, et al. Rôle de l’imagerie par résonance magnétique dans l’exploration des cholangiocarcinomes hilaires. La Presse Médicale. 2018;47:950-60.

[Crossref]

- Nfally B, Akpo G, Deme H, et al. Place de la bili-IRM dans le diagnostic etiologique des icteres cholestatiques à Dakar. Pan Afr Med J. 2016;24.

- Echchikhi M, Edderai M, Saouab R, et al. H. Mise au point sur les variantes anatomiques des voies biliaires extra-hépatiques en cholangio-pancréato-IRM et leurs risques de complications. Journal d'imagerie diagnostique et interventionnelle. 2021;4:307-16.

[Crossref]

- Guillaume P, Tuyéras G, Lopez R, et al. Implantation du conduit cystique dans le conduit hépatique gauche: une variation anatomique rare de la voie biliaire accessoire. Morphologie. 2019;103:100.

[Crossref]

- Losanoff JE, Kjossev KT, Katrov E. Hepaticocystic duct--a case report. Surg Radiol Anat. 1996;18:339-41.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Malaussena, Nicolas. Apport de la cholangio-IRM dans la prise en charge de la pathologie lithiasique. PhD diss. 2021.

- Kara MK, Bloomston M. Anatomy and embryology of the biliary tract. Surg Clin North Am. 2014;24:203-17.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- de Cássia Santos CD, Gonçalves GR, Scabora JE, et al. Morphometric Study of Extra-Hepatic Biliary Pathways-Study in Human Corpses. Int J Morphol. 2022;40:228-32.

- Lamah M, Dickson GH. Anomalies congénitales des voies biliaires extra-hépatiques: évaluation d'une expérience. Surg Radiol Anat. 1999;21:325-27.

[Crossref]