Review Article - Journal of Primary Care and General Practice (2021) Volume 4, Issue 1

Interventions to improve care coordination in primary care: A narrative review.

Regula Cardinaux1, Nicolas Ochs1, Carole Michalski2, Jacques Cornuz1, Nicolas Senn1, Christine Cohidon1*

1Department of Family Medicine, University of Lausanne, Switzerland

2Faculty of Biology and Medicine, University of Lausanne, Switzerland

- Corresponding Author:

- Dre C. Cohidon

Center for Primary Care and Public Health (Unisanté)

Department of Family Medicine

University of Lausanne

Switzerland

E-mail: Christine.cohidon@unisante.ch

Accepted date: December 08, 2020

Citation: Cardinaux R, Ochs N, Michalski C, Cornuz J, Senn N, et al. Interventions to improve care coordination in primary care: A narrative review. J Prim Care Gen Pract 2020:4(1):61-79.

Abstract

Background: Care coordination in primary care is one of the main challenges for the future of health systems. We reviewed the literature to identify interventions that could improve coordination in the primary care setting. Methods: We conducted a literature review of articles referenced in the PubMed database between January 2000 and Avril 2020, (MESH terms: “Primary Care / Primary Health Care”, “Coordination / Care Coordination / Coordinated Care / Coordinating” and “Physician / General practitioner / Family practitioner / Primary care providers”). Two independent reviewers took part in the selection, data extraction and content analysis. All individual similar interventions were pooled and described for their overall benefit / harm on patients’coordination. Interventions were grouped according to categories described in the literature. Results: We found 4044 publications, of which 103, evaluating care coordination interventions, met inclusion criteria. We classified 62% of care coordination interventions into the category "Structuring relationships between service providers and patients" and 59% into "Systems to support the coordination of care”. The interventions involving "case managers", "multidisciplinary teams", "patient education" "care plans", and "electronic health records" were associated with the greatest number of articles describing positive effects. Conclusion: This narrative review illustratesthe wide variety of studied interventions to optimize the coordination of care in primary care. Future research assessing impact of these interventions on patient management are necessary.

Introduction

The increasing numbers of elderly and chronically ill patients places a considerable burden on the health care system, including a significant impact on costs [1]. As a result, many industrialized countries have begun reviewing their health systems to provide better care for these types of patients. One of the major challenges is reducing care fragmentation, principally by improving continuity of care and developing care coordination is one way to tackle this [2, 3]. In this context, primary care (PC) is well placed to play a major role in the management of patients with multiple, complex medical problems and functional impairment. For example, promoting care at home by strengthening outpatient management may help respond to hospital congestion, improve the quality of life of patients and reduce costs at the same time [1]. However, this requires a fundamental rethink of primary care organization, especially reinforcing care-coordination aspects within practices without overloading PC teams.

In a literature review on care coordination published in 2007, from more than 40 identified care coordination definitions the authors compiled the following working definition of care coordination: Care coordination is the deliberate organization of patient care activities between two or more participants (including the patient) involved in a patient’s care to facilitate the appropriate delivery of health care services. Organizing care is often managed by the exchange of information among participants responsible for different aspects of care” [4]. A care coordination framework therefore involves several health partners around the care. Ideally, it should provide appropriate patient-centered management, limiting fragmentation of care, loss of information, treatment errors and redundancy of examinations and emergency department visits [5].

In 2006, Powell Davies published a literature review on interventions relating to care coordination in the general practice [6]. The most frequently reported interventions showing beneficial effect on patient health were relationships between service providers (65.5%), coordination of clinical activities (61.3%) and use of systems to support the coordination of care (60.5%) while studies reporting an effect on patient satisfaction were those tending to improve relationships between service providers (66.7%), support for clinicians (57.1%), communication between service providers (54.5%) and support for patients (50.0%).

Many health system organization changes have taken place over the past 15 14 years worldwide, particularly in PC and interventions aimed at improving care coordination in family practice have been the subject of an increasing number of scientific studies [7, 8].

Our narrative review aims to identify and describe recent care coordination interventions in PC and describe their effects on patient care management from 2000 to 2020.

This review was performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement.

Search strategy

We conducted a narrative review of the Medline Ovid SP database (through PubMed) from January 2000 to April 2020, using the following MESH terms: “Primary Care / Primary Health Care”, “Coordination / Care Coordination / Coordinated Care / Coordinating” and “Physician / General practitioner / Family practitioner / Primary care providers”.

Data sources and search

Two independent reviewers examined and selected articles in two stages. A first selection was based on the article title. The second selection was after reading the article abstract. Disagreements related to selections were resolved through discussion to reach consensus. The inclusion criteria are the MESH terms detailed above. We retained interventional, observational, and qualitative studies as well as expert opinions.

The exclusion criteria were no link to care coordination or general medicine, or a too specific target population (for example, children only, American veterans, Australian aborigines, single disease). We also excluded paid articles and non-English- or non-French-language articles.

Data extraction

The same two researchers extracted data from the articles using a standardized predefined data extraction form we built, containing the major characteristics of the articles including, year and country of publication, type of study, care coordination interventions, results obtained. If a study was assessing multiple interventions strategies, each individual intervention was extracted. This explains why the sum of the percentages presented in (Table 1) is greater than 100. We also classified coordination interventions according to the nine categories of Powell Davies et al. with addition of a new category related to practice facilitators (Table 1). Extending the classification of Powell Davis et al, [6] we now produce a comprehensive directory of the studied care coordination interventions including precise definitions of each individual intervention.

| Category Number |

Intervention category | % of papers (N=103) |

| 1 | Communication between service providers | 21.4 |

| 2 | Systems to support the coordination of care | 59.2 |

| 3 | Coordinating clinical activities | 32.0 |

| 4 | Support for service providers | 30.1 |

| 5 | Structuring the relationships between service providers and patients | 62.1 |

| 6 | Support for patients | 31.1 |

| 7 | Joint planning, funding and/or management | 0 |

| 8 | Organizational agreements | 7.8 |

| 9 | Organization of the health care system | 14.6 |

| 10 | Facilitator (additional category) | 1.9 |

Table 1: Classification of studies included in the review, adapted form Powell Davies et col.

Data synthesis and analysis

We the same two researchers qualitatively described and evaluated the different types of interventions as having globally: 1) an effect on care coordination (positive or negative) or 2) no effect on care coordination (as used in other studies). Disagreements were resolved during discussion, and when necessary, a third author was consulted. Our evaluation was according to the results of the intervention study, regardless of the measured outcome (e.g. doctor's experience, measurement of blood pressure, patient satisfaction). Finally, articles not describing interventions but only opinions of professionals regarding care coordination, initially selected, were classified as "not applicable, NA".

Results

Articles included in the study

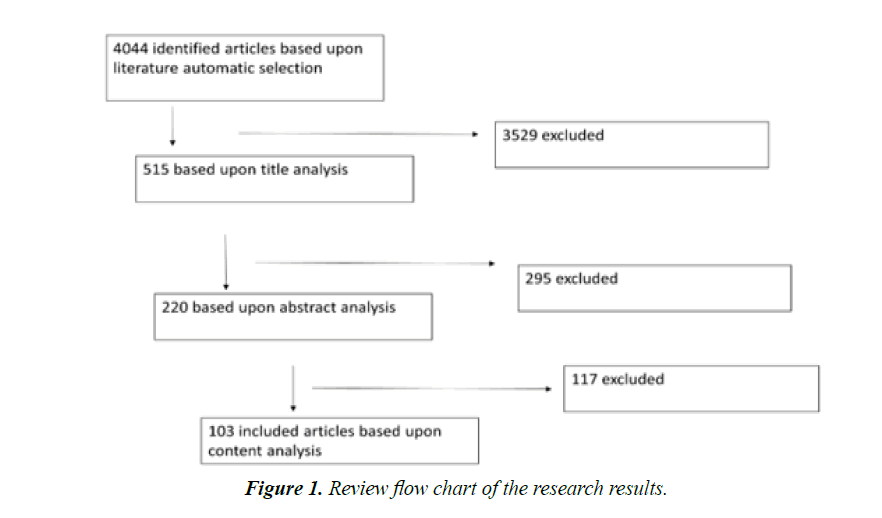

We identified 4044 articles in the initial screen. After the first selection based on the title, 515 articles were retained and after a second selection step reading the abstracts, 220 were kept. Finally, we read articles entirely and selected 103 articles for analysis and data extraction (Figure 1).

Classification of selected articles according to the types of interventions and their effects

From the 103 articles, we identified 26 different types of intervention (sometimes evaluated in combination) and classified them into the 10 specified categories (the 9 categories proposed by Powell Davis et al and the one added regarding practice facilitators) [6]. More than half of the articles described interventions aimed at ‘using systems to support the coordination of care’ (59% of articles) and ‘structuring the relationships between service providers and patients’ (62%). To a lesser extent, articles described interventions targeting ‘coordinating clinical activities’ (32%), ‘support for patients’ (31%), and ‘support for service providers’ (30%). Interventions regularly involving higher organizational levels (associations, federations, governments) or political policies concerning payment methods, laws, or arrangements were significantly less represented (15% in total). (Table 2).

| Category | Intervention | Definition |

| 1. Communication between service providers | Case conference involving PHC providers | Formal meeting between the FD and / or CM and / or other specialists to discuss patient management. |

| 2. Systems to support the coordination of care | EHR | Electronic Health Record: Digital version of a patient’s medical file and / or simple administrative list at several levels of interconnection. |

| Telephone | Intervention using telephone contact to improve care coordination | |

| Care plan | Care plan implemented by the CM alone and / or by the FD and / or by the specialist to manage a specific patient | |

| Proformas | "Pre-formatted" "standardized" forms (such as a physiotherapy voucher) that FDs must complete to address their patient to a specialist | |

| Telecare | A device plays the role of "care provider" and measures vital parameters or quantifiable values and sends them to appropriate health professional | |

|

Multidisciplinary joint consultation | Consultation with several health professionals at the same time, which does not specify a place or type of carhealth provider |

| Joint care provider appointment arrangements | Organization of appointments by someone other than the patient as well as a procedure in the consultation schedule | |

| Care provider arrangements | A written form, such as a contract, specifying, for example, ways to address patients to any health professional | |

| Priority access to specialists | Existing agreement between health professionals to facilitate patient access to specialists | |

|

Care provider training | Training in the form of workshops or courses to train the FD / health professional for a particular intervention |

| Guidelines | Protocols or guidelines promoting the coordination of care within the practice as they determine which health professional (s) is involved | |

| Reminder system | ‘Callback’ system most often using computers | |

| Supervision for PC clinicians | Supervision or advice to a health professional from another more experienced health professional (FD, specialist, senior nurse) | |

|

Case management /manager | Caregiver generally other than the FD responsible for coordinating care of patient with one or more pathologies |

| Co-location | Grouping in the same building of several different health professionals | |

| Multi-disciplinary team | Several people working in the same team structure (practice team from assistant to doctor) | |

|

Patient education | Courses given to the patient to increase autonomy concerning care and understanding of the disease |

| Assistance for patients for appointment | System to facilitate access to patient care | |

| Family caregiver education | Same principle as patient education but addressed to ‘family’ caregivers surrounding patient | |

| 7. Joint planning, funding and/or management | No intervention defined | - |

|

Formal agreement involving PC organization | Operational agreement between primary care group practices (clinics) and other care facilities |

|

Gate-keeping / Having a doctor | Gate-keeping Health System (gateway to the health system) |

| Pay-for-performance | Compensation payment system based on composite grids. | |

| Capitation payment | Each doctor receives a sum X per patient he treats according to certain criteria (age, sex, number of comorbidities). | |

| 10. Facilitator (additional category) | Facilitator | Person helping the practice to organize and prioritize activities related to quality improvement |

Table 2: Definition of the interventions

The characteristics of the selected studies are presented in detail in (Table 3).

| Authors | Setting/Population | Intervention/Objective | Type/Design | Results |

| Aller, et al. (Spain 2017) [87] |

26 primary and 24 secondary care doctors | To analyze doctor's opinions on the contribution of mechanisms to improve clinical coordination between primary/secondary care and the main factors influencing their use. | Qualitative descriptive study | Feedback and programing mechanims : Shared medical record, Clinical case conferences, Shared protocols |

| Ang et al. (Singapour 2019) [18] |

684 patients that were right-sided to Frontier FMC and matched controls (stable chronic condition) | To evaluate the impact of the Right-Site Care Programme with Frontiers Family Medicine Clinics (FMC) in reducing mortality, healthcare utilization frequencies and healthcare utilization charges. Use of common HER and multidisciplinary case conferences |

Retrospective quasi-experimental study | ↓ 3-year mortality Lower polyclinic attendance frequencies and charges. |

| Ballo et al. (Italy 2018) [88] |

1761 patient with definite chronic heart failure (HF) and 2522 control patients | To investigate the clinical utility of a Chronic Care Model (CCM)-based healthcare project for the management of HF patients | Retrospective matched cohort study (follow-up 4 years) | Higher hospitalization incidence and lower risk of death in the CCM group; |

| Banfield et al. (Australia 2013) [27] |

17 participants with planning and quality improvement roles (nurses, allied health professionals, physicians and managers in practice) |

Exploration of the way that information continuity supports coordination | Qualitative study. In-depth semi-structured interview. | Availability of information is not sufficient to ensure continuity for the patient or coordination from the systems perspective |

| Barsanti et al. (Italy 2019) [62] |

178 GP in a primary care center (PCC) and 2958 GP not involved in a PCC |

To analyze the possible benefits of the co-location of services in primary care in terms of perceptions regarding various domains of integration. | Cross sectional study | Positive impact in terms of collaboration between professionals No effect in terms of clinical and system integration ↑ providers satisfaction |

| Bonciani et al. (European countries 2018) [63] |

7183 GPs and 61,931 patients | To analyze the relationships between GP co-location with other GPs and/or other professionals (interprofessional collaboration) and the use of clinical governance tool and interprofessional collaboration (from GPs’ practices and patients’ experience). | Cross sectional study | Association with positive GPs’ outcomes ↓ patients experience regarding access, comprehensiveness and continuity |

| Buja et al. (Italy 2019) [89] |

602 GPs total of 753'366 patients (with 47'575 diabetic) (MEDINA project) |

Examine how the 3 types of proactive primary care model (CCM, expanded CCM, Kaiser Permanente Model) adopted in Italy were improving the quality diabete management by GPs. | quasi-experimental before / after study |

↑ GPs performance scores related to diabetes management when new models are adopted |

| Carrier et al. (USA 2012) [73] |

31 healthcare providers participating in Care Coordination Agreements (CCAs). 6 national thought experts and/or leaders in care coordination. | To explore factors related to Care Coordination Agreements implementation | Qualitative study. Semi-structured interviews. | Usefulness of CCA that address referral and access processes Successful CCAs in settings where both parties already have stable communication pathways (EHR, designated staff) and strong working relationships |

| Ciccone et al. (Italy 2010) [24] |

30 care managers in offices of 83 GPs. 1,160 patients with cardiovascular disease or at risk ,diabetes, heart failure, | To test the disease and care management (D&CM) model Leonardo with “care manager” nurses in primary health care system | Feasibility study. Impact evaluation. |

Good feasibility Highly effectiveness in increasing patient health knowledge, self-management skills, and readiness to make changes in health behaviors |

| Clarke et al. (USA 2015) [49] |

28 primary care practice sites: 1 comprehensive care coordinators (CCC) in each of 14 practices with intervention. CCCs touched 10,500 unique patients over a 1-year period | Evaluation of the implementation of a comprehensive care coordinator (CCC, non-licensed personnel) within the practice on emergency department visits. | Matched case-control differences-in-differences. | CCC intervention group had a 20% greater reduction in its prepost ED visit rate |

| Cohen et al. (USA, 2016) [26] |

328 primary care practices randomly selected, already involved in a program to adopt electronic health record (HER) | To identify barriers in the use of HER in order to exchange, and reconcile key information during patient care transitions | Cross-sectional design | Identified barriers: - difficulty sending and receiving patient information electronically, - lack of time, - complex workflow changes required. |

| Cohen et al. (USA, 2011) [56] |

9 practice-based research networks in primary care | To explore the use of coordinated care to address patients’health behavior change needs | Qualitative evaluation (multi-methods) | Best way to improve health behaviors: in practice health risk assessment, brief counseling, referral, counseling resource. Facilitators: Automated prompts and decision support tools, trainings in counseling strategies, co-location |

| Collinsworth (USA 2013) [25] |

5 community clinics: 806 patients enrolled in the Diabetes Equity Program (DEP). 5 DEP Community Health Workers and 7 Primary Care Providers (6 physicians and 1 nurse practitioner) |

To evaluate the effectiveness of a Community Health Worker (CHW)–led diabetes self-management education (DSME) program | Before-after study Mixed methods |

↓ A1C levels and blood pressure ↑ Patients-providers collaboration |

| Cramm & Nieboer (The Netherlands 2012) [52] |

22 Primary care practices that had implemented the Chronic Care Model | To evaluate the impact of Chronic Care Model (CCM) implementation on quality of chronic care delivery | Two repeated cross-sectional surveys | ↑ Chronic illness care delivery over time Gains attributed primarily to improved relational coordination, raising the quality of communication and task integration among professionals from diverse disciplines with common objectives |

| Cramm & Nieboer (The Netherlands 2012) [53] |

188 professionals in 19 disease-management programs | To evaluate relational coordination between GPs and other professionals and to assess impact on chronic illness care delivery | Cross-sectional study design | ↑ Quality of chronic illness delivery with relational coordination |

| Davidow et al. (USA 2018) [90] |

11 primary care physicians /cardiologists dyad | To improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the referral process between PCP and cardiologists | Before-after study | ↑ closed referrals on time and clinical question answered Better understanding of their condition by patients ↑ satisfaction PCP and specialists |

| De Busk et al. (USA 2004) [36] |

462 patients hospitalized for heart failure with clinical criteria | Effectiveness of a telephone-mediated nurse care management program for heart failure | Randomized Controlled Trial (Intervention: 228 / control: 234) | No difference in the rate of first rehospitalization for heart failure and all-cause. |

| de Stampa (Canada & France 2013) [79] |

35 PCPs, 7 Case Managers, and 4 geriatricians from 2 integrated models of care for frail, elderly patients (SIPA and COPA). | To explore the clinical collaboration among (PCPs), case managers and geriatricians in integrated models of care | Qualitative study | - Good collaboration between CMs and geriatricians - Real collaboration between CMs and PCPs only later and mostly fostered by the interventions of the geriatricians - PCPs and geriatricians collaborated only occasionally |

| Dent & Tutt (UK 2014) [91] |

2 National Health Service primary care trusts and their network (e.g. acute hospitals, social care, private care homes): 44 health professionals and information specialists | Examination of the challenges of e-patient information systems’ support for integrated care pathways. | Qualitative evaluation of a range of e-patient information systems | Informatics services as well as users have to be adaptable for implementing electronic integrated care pathways, which implies considerable involvement of change facilitators |

| Desborough et al. (Australia 2016) [40] |

678 patients, from 21 general practices, who received nursing care between September 2013 and March 2014. Interviews with 16 nurses, 23 patients and 9 practice managers. | To evaluate nursing care in general practice in terms of patients enablement and satisfaction. | Mixed methods study: Patient enablement and satisfaction quantitative survey. Nurses interviews. | ↑ Patient’s satisfaction and enablement with longer nurse consultations ↑ Patient’s satisfaction when continuity of care with the same general practice nurse ↑ Patients’ satisfaction and enablement with nurses with broad scopes of practice and high levels of autonomy |

| Di Capua (USA 2017) [92] |

459 staff and physicians and 13,441 patients in 26 primary care practices | To evaluate the implementation of care coordination program in terms of patients experience and team dynamic | Before-after study | ↑ Patient experience with staff No disruption of the team dynamics |

| Donohue et al. (USA 2015) [93] |

46 PCPs members of a research and education Network and 26 PCPs whom patients are included in a survival clinical trial | To assess PCPs’ perspectives regarding electronic health record-generated care plans (provider-to-provider communication) for cancer survivors | Cross-sectional survey | EHR-generated plans useful in - coordinating care, - understanding treatments & treatment adverse effects - supporting clinical decisions Facilitators for use: - consistent provision - standard location in medical record - plan tailored to PCP use |

| Doty et al. (11 countries, 2012) [50] |

Patients having participated in the 2010 Commonwealth Fund International Health Policy Survey and who reported seeing more than 1 physician in the past year: 11 207 adults (from 11 countries) | To study associations between having a care coordinator, care access, strong health care provider–patient relationship and care coordination | Cross sectional survey Data from the 2010 Commonwealth Fund International Health Policy Survey (Patients experience with health care system). |

- Having care coordinator: ↓ Coordination problems Accessible care: ↓ Coordination gaps - Strong health care provider–patient relationship: ↓ Coordination gaps related to medical records or repeated tests and lack of follow-up after a hospital and/or ER discharge |

| DuGoff et al. (USA 2019) [57] |

142'016 physicians who shared at least one patients with another physician; at least one physician is a PCP | To explore the predictors of and implications of persistence of PCP connections with their colleagues over time | Exploratory study | Regions with higher persistent ties tended to have lower rates of emergency room visits. Regions where PCPs had more physician connections were more likely to have higher emergency room visits. |

| Duhigg et al. (USA 2018) [94] |

895 Primary care practices and 23'292 patients. | To compare practices offering open access (OA) to care to practices without OA in terms of patients’ experience of care. | Two-group mean comparisons, matched case-control differences | Minimal impact of OA to care on patients’ experience in primary care |

| Easley et al. (Canada 2016) [95] |

58 care providers: 21 FPs, 15 surgeons, 12 medical oncologists, 6 radiation oncologists, and 4 GPs in oncology | To explorer coordination of cancer care between FPs and cancer specialists | Qualitative study, semi-structured telephone interviews | Communication challenges 1. System-level: delays in medical transcription, access to patient information 2. Individual-level: lack of rapport between FPs and cancer specialists, lack of clearly defined and broadly communicated roles |

| Fabre et al. (USA 2020) [19] |

Rural federally qualified health center (FQHC) including 9 primary care centers | to improve internal referral process and to support patients in the process | Before–after study | ↓ referrals ordered: decrease ↑ referrals performed: ↑ referrals completed within 90 ↑ referrals reviewed within 90 days |

| Fagan et al. (USA 2010) [37] |

Claims files of a Managed Care Organization (MCO) regarding 20,943 adults aged 65 and older with diabetes, receiving care. | Evaluation of a practice-based care coordination program, plus a pay for performance (P4P) for meeting quality targets, and plus a third-party disease management on quality of care and resource use | Before-after study including a control group. Intervention: 1,587 patients / control: 19,356 patients |

↑ Quality of care for both groups. Slight differences between intervention and comparison group trends and changes in trends over time |

| Fagnan (USA 2011) [96] |

6 Rural PC practices. (clinician champions, clinician partners, practice administrators, and nurse care managers) | Evaluation of an office-based nurse care management model for complex patients, Care Management Plus | Qualitative evaluation Semi-structured interviews | Variations in the model acceptability Practice change requires time, and is supported by practice reflection and on-going facilitation |

| Forrest et al. (USA 2003) [97] |

14'709 primary care practice office visits, referred and nonreferred, made by privately insured, nonelderly patients, seen by 139 primary care physicians in 80 practices | Examination of the influence of gatekeeping arrangements and capitated primary care physician (PCP) payment on the specialty referral process in primary care settings. | Analysis of insurance database | No difference in referral process among various health plan type Patients in plans with capitated PCP payment more likely to be referred for discretionary indications than those in non- gatekeeping plans. |

| Freund et al. (Germany 2016) [28] |

115 small primary care practices: 2076 patients with type 2 diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or chronic heart failure and a high risk of hospitalization | Evaluation of a protocol-based care management (structured assessment, action planning, and monitoring) by medical assistants for high-risk patients. | Cluster randomized clinical trial | No differences of all cause hospitalizations ↑ quality of life |

| Gallo et al. (USA, 2004) [61] |

127 primary care clinicians in 54 clinics on 11 sites primary care research in substance abuse and mental health for the elderly (PRISM-E) | To compare 2 models for older patients with mental health disturbances: 1.integrated behavioral health care within primary care practices 2. Enhanced referral care to separate specialty clinics. |

Randomized trial. Multisite effectiveness assessment | Integrated care within practices ↑ Communication between primary care clinicians and mental health specialists ↓ Stigma for patients ↑ Coordination of mental and physical care |

| García et al. (Spain 2011) [51] |

230 GPs and 14 primary health care units. Nephrology Department of the University Corporation. Patients with kidney diseases and difficult-to-control AHT. | To evaluate the implementation of a coordinated programme between nephrology university Department and primary care for referral of patients. | Observational study Data from a clinical information system |

↑ Referral criteria between PC and specialized nephrology service ↑ Prioritization of visits ↑ In referrals denied by specialists |

| Gardner & Sibthorpe (Australia 2002) [42] |

All stakeholders (plus patients representatives, pharmacists, specialists and GPs representatives) involved in the implementation of coordinated care for patients with complex needs | To explore the barriers to correctly implement a trial of coordinated care with GPs as coordinators. | Randomised Controlled Trial. Qualitative evaluation (in-depth interviews with key stakeholders and observation of trial processes). | - Stakeholders did not fully endorse the trial’s key goals – GPs unable to become effective purchasers - Increased gatekeeping never not fully realized, - Cost-saving strategies were not taken up - Improvements in continuity of care impeded by limited provider networks and GP reluctance to collaborate with other providers |

| Goetz Goldberg et al. (USA 2012) [9] |

6 primary care practices, including 38 clinicians and administrative staff | To explore experiences and perceptions of the use of EHR | Qualitative case study over a 16-month period | ↑ Efficiency in retrieving medical records, storing patient information, coordination of care, and office operations. |

| Graetz et al. (USA 2009) [10] |

Integrated delivery structures of care (Kaiser Permanente): 565 primary care clinicians (physicians, nurse practitioners and physician assistants) | Implementation of an integrated EHR system. | Observational Study (2005 & 2006) | ↑ Information access ↑ Agreement on treatment goals and plans No association between EHR use and being in agreement on roles and responsibilities with other clinicians. |

| Graetz et al. (USA, 2014) [14] |

Integrated delivery structures of care (Kaiser Permanente): 565 primary care clinicians (physicians, nurse practitioners and physician assistants). | Staggered implementation of an outpatient EHR, followed by an integrated inpatient EHR. | Three repeated observational surveys (2005, 2006 & 2008). | ↑ Access to complete and timely clinical information ↑ Agreement on clinician roles and responsibilities for patients transferred across clinicians. |

| Graetz et al. (USA, 2014) [20] |

Integrated delivery structures of care (Kaiser Permanente): 565 primary care clinicians (physicians, nurse practitioners and physician assistants). | Evaluation of an integrated outpatient-inpatient EHR with staggered implementation (2005-2010). | Three repeated observational surveys (2005, 2006 & 2008). | ↑ Teams cohesion: ↑ Access to information ↑ Agreement on treatment ↑ Agreement on responsibilities |

| Gray et al. (USA 2019) [78] |

35 patients & 36 family members 21 physicians |

Exploration of the concept of the medical team “quarterback” by patients and physician's (actions and themes associated with that role). | Qualitative study - ethnographic approach including 9 focus groups | Associated with 6 major themes: - takes responsability for overseeing the big picture of a patient's care - coordinates care - advocates for the patient - practices proactive communication - engages in proactive and persistent problem solving |

| Gum et al. (USA 2015) [29] |

Home-based providers, primary care practices and 7 older adults requiring coordination. | Evaluation of a communication protocol, ‘BRIDGE (Binging Inter-Disciplinary Guidelines to Elders, including scripted telephone calls, structured progress reports sent to primary care practices ) in addition to Depression care management (DCM) by home-based providers | Open pilot trial | ↓ Depressive symptoms and disability Good satisfaction of participants |

| Haggerty et al. (Canada 2008) [70] |

100 primary health care clinics, 221 GPs, secretaries and director, and 2725 patients. | Identification of attributes of clinic organization and physician practice that predict patient-reported accessibility, continuity, and coordination of care. | Cross-sectional observational study | ↑ Accessibility and coordination continuity in practices with evening and continuous telephone access and operational agreements access with other health care establishments |

| Haley et al. (USA 2015) [98] |

9 PCPs and 5 nephrology practices. Data collected from 292 eligible patient records, 157 audited pre- and 135 audited post implementation. Patient eligibility: older than 50 years, at risk for chronic kidney disease (CKD), with a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and hypertension. |

To evaluate the use of tools (from Renal Physicians Association toolkit) and to improve identification of CKD, communication, and comanagement between PCPs and nephrologists. | Before-after study. Qualitative evaluation. |

Among PCPs: ↑ CKD identification, ↑ Referral to nephrologists, ↑ communication & execution of co-management plans Among nephrologists: ↑ Referral and co-management processes |

| Hefner et al. (USA 2019) [12] |

17 patients with cardiopulmonary conditions at 3 Department of Family medicine clinic sites | To explore how experienced portal users engage with secure messaging to manage their chronic conditions (through an application allowing patients to access their electronic health record, request appointments and medication refills, and communicate with providers through secure messaging) | Exploratory qualitative study 3 focus groups |

Motivation - quicker than calling the office - direct to access to physicians Uses for care management: - extension of the office visit - coordination of care Challenges: - technical challenging - worry about physician time spent responding to messages - determining what constitute a "non-urgent" message |

| Holzel et al. (Germany 2018) [45] |

71 primary care physicians and 248 patients >= 60 y. diagnosed with unipolar depression or with moderate depressive manifestations | To compare GermanIMPACT intervention (IG, including a care manager) with treatment as usual (CG, control group) | Cluster-randomized, controlled study | Remission rate at 12 months in IG significantly higher than in group control (25.6% vs10.9%) |

| Jones et al. (USA, 2015) [11] |

58 clinicians, including 32 in four hospitalist focus groups, 19 in three PCP focus groups, and 7 in one hybrid group with both hospitalists and PCPs. | To identify challenges in care coordination from the perspective of PCPs and hospitalists | Exploratory qualitative study (focus group). | Hospitalists and PCPs common themes of successful care coordination: 1. ↑ Efforts to coordinate care for “high-risk” patients, 2. ↑ Direct telephone access to each other, 3. ↑ Information exchange through shared electronic medical records, 4. ↑ Interpersonal relationships, 5. Clearly defined accountability. Hospitalists and PCPs similar care coordination challenges : 1. Lack of time, 2. Difficulty reaching other clinicians, 3. Lack of personal relationships with other clinicians, 4. Lack of information feedback 5. Medication list discrepancies 6. Lack of clarity regarding accountability for pending tests and home health |

| Katon et al. (USA, 2010) [22] |

14 Primary care clinics, 214 participants with poorly control diabetes, coronary heart disease, depression | Collaborative care management (nurse and family physician), provided guideline-based | Randomized Controlled Trial | Improvement HbA1c, LDL cholesterol and score of depression ↑ Patients quality of life & satisfaction |

| Kautz et al. (USA 2007) [99] |

222 patients who received primary unilateral total knee arthroplasty at the same surgical department of a large Integrated Delivery System (IDS)’ acute care hospital | Assessment whether receiving care from providers who belong to the same IDS improves patient-perceived coordination of care. | Before-after study (baseline and 6-week post-operation patient surveys) | No consistent effects of IDS membership on patient-perceived coordination of care |

| Kim (USA 2013) [66] |

Medicaid beneficiaries with disabilities, aged 20-64 (N=5064) | Effectiveness of a telephone care management intervention to reduce use of care (ED, hospital admissions, GP and specialists visits) | Randomized Controlled Trial (Intervention: 3540 / control: 1524) | No significant difference between intervention and control group |

| Krousel-Wood (USA 2018) [13] |

53 GPs from primary care clinics | To assess changes in the percentage of providers with positive perceptions of EHR benefit | Longitudinal analysis (baseline, 6/12 months ,12-24 months) | ↑ patient communication, hospital transitions, preventive care prompt, satisfaction with system reliability ↓ satisfaction with ease of use |

| Lee et al. (Corea 2017) [77] |

1013 adults with Diabetes Mellitus. (Korean health panel data) |

To study the association between having a regular doctor and ED visits. | Cross sectional study | ↓ ED visits in patients having a regular doctor, especially for those offering a good comprehensiveness of care and long relationship |

| Low et al. (Singapore 2015) [41] |

259 medically complex patients | To evaluate a Transitional home care program including multi-disciplinary team, nurse case manager, home visits with comprehensive assessment of the patient’s care needs within the first week of hospital discharge, individualized patient-centered care plan | Before-after study | ↓ Hospital admissions ↓ Emergency department attendances ↓ Hospital bed days at 3 and 6 month post program enrollment |

| Lubloy et al. (Hungary 2017) [74] |

31' 070 patients with diabetes over 40 years with care shared between GPs and specialists | To study the associations between GPs and specialists collaboration and prescription drug cost | Analysis of administrative healthcare data | ↓ Prescription drug costs when strong relationship between GP and specialists |

| Ludwick et al. (Canada 2010) [100] |

9 GPs 6 hospital-, and academic-based physicians |

To understand how remuneration and care setting affect the implementation of electronic health records (EHRs). | Qualitative study | No remuneration approach supports EHR adoption any more than another |

| Manski-Nankervis et al. (Australia 2015) [101] |

78 general practices:174 GPs, 115 practice nurses | To study the associations between characteristics of GP settings and primary healthcare providers and the degree of relational coordination, in insulin initiation for people with type 2 diabetes | Cross-sectional study | Poor relational coordination in female GPs and older practice nurses ↑ Relational coordination in practice nurses with diabetes educator qualifications and experience in insulin initiation |

| Martinussen (Norway 2013) [72] |

1298 hospital physicians randomly selected | To investigate the quality of referral letters from GPs to hospitals and communities. | Combination of survey data for hospital physicians with information on the hospitals and their communities. | Only 15.6% of the hospital physicians perceived the quality of the referrals to be "usually good" (barriers: lack of information in referrals and inappropriate referrals) |

| Mastal et al. (USA 2007) [46] |

Medicaid beneficiaries with diabilities | Innovative practices in two disability care coordination (DCCO) programs, with DCCO roles of care manager co-located in primary care and behavioral clinical settings | 2 Case-studies | ↓ Hospital days ↑ Provider knowledge ↑ Patient access ↑ Consumer self-efficacy |

| May et al. (Scotland 2011) [71] |

221 professionals, including health professionals, managers, patients, social care professionals, service suppliers and manufacturers. Involved in telecare services in community and domestic settings | Identification of factors inhibiting the implementation and integration of telecare systems for chronic disease management in the community | Qualitative study | Key barriers: - uncertainties about coherent and sustainable service and business models; - lack of coordination across social and primary care boundaries, - lack of financial or other incentives, - lack of a sense of continuity with previous service provision and self-care work undertaken by patients, - uncertainty about adequacy of telecare systems, - poor integration of policy and practice. |

| McCullough (USA, 2014) [15] |

Physician practices and health centers: 24 providers, physicians, administrators and office staff | Implementation of electronic Health Information Exchange (HIE) | Qualitative study. Key-informant interviews | ↑ Care coordination ↑ Productivity |

| Mills et al. (Australia, 2003) [31] |

398 patients with type 2 diabetes, PC professionals | Evaluation of the Patient-centered care plan model with patient goals. | Descriptive part of a matched geographically controlled trial. Before after study | ↑ Health outcomes for 40-60% of patients ↓ Hospital and medical expenditure for some patients. |

| Moe et al. (Canada 2018) [102] |

4600 patients with a visit to a family physician in a WPCN (Westside Primary Care Network) at least once in the previous 18 months | To examine patients’ perceptions of care outcomes following the introduction of collaborative teams into community family practices | 4 cross-sectional studies (2007, 2010, 2013, 2016) | No global improvement of patients experience with team-based initiative. Heterogeneous results according to the indicators |

| Moore et al. (Canada, 2012) [23] |

Elderly people at home, (N=25) | Collaborative Care Program including 1 nurse practitioner, 1 GP, 1 registered practical nurse | Qualitative and quantitative evaluation | ↑ Satisfaction patients & care providers |

| Noël et al. (USA 2013) [54] |

Patients with Type 2 diabetes. 283 practice members (i.e., physicians, non-physician providers, and staff) from 39 clinics. | To investigate which components are associated with implementation of chronic care models | Cluster randomized controlled trial | ↑ Implementation of care coordination models with relational coordination and reciprocal learning among team members |

| O’Malley et al. (USA 2010) [21] |

52 physicians or staff from 26 practices, 8 thought leaders: clinicians active in HIT efforts and EMR vendor medical directors. | Use of commercial EHRs | Qualitative study. Semi-structured interviews by phone. | ↑ within-office care coordination EHRs less able to su |